How to bob dance

Through Flash Mobs, Bob’s Dance Shop Spreads Joy — and Cardio

It’s 2017, and the sun is shining down on the bustling Third Street Promenade in downtown Santa Monica. We see a man in a yellow bowling shirt, sleeves rolled up, back embroidered in purple: Monterey Park Lions. The beat kicks in, and he snaps and taps as we zoom in on his feet: white Converse high-tops. Dancing shoes.

As he dance-walks down the street, a crowd has gathered, keeping far enough to be entertained. The horns kick in; he passes a telephone booth. Its user jumps out, and they synchronize moves. This repeats, picking up person after person until a group of ostensible former strangers have now formed in the middle of Promenade, shimmying in unison, with whiffs of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” in the shoulder-shrugging, leg-dragging choreography.

The crowd is delighted. It’s performance art. It’s a dance party. It’s fun. And as we zoom in on the front of the yellow bowling shirt, we see a name embroidered: “Bob. ”

“Everything I did from childhood through college was ultimately preparing me for what I’m currently doing, which is curating vibes,” says Andrew “Coco” Coconato, who alongside choreographers, dancers, and close pals Lucas Hive, Kameron com K, and Jacob T. Garcia — aka the Bobettes (or Bobs, if you’re being more casual) — created the phenomenon we know today as Bob’s Dance Shop.

His devotion to the mob life began in senior year of high school, when he discovered dance through watching Michael Jackson. “I learned ‘Thriller,’ and taught my senior class the ‘Thriller’ dance. And it was like: Oh my gosh, I love this, I’m good at it, I’m passionate about it, and I want to keep doing it,” he says.

In college he choreographed dances for his fraternity, and organized 300-person flash mobs. “Because I had my ‘straightjacket’ on, and I was closeted, I had a lot of sexual energy that I was not using. So I channeled all of it into my creativity and leadership.”

“Because I had my ‘straightjacket’ on, and I was closeted, I had a lot of sexual energy that I was not using. So I channeled all of it into my creativity and leadership.”

“Bob is an instant energy. I call it the paradise for self-expression. You’re Bob, I’m Bob, we’re all Bob. It represents liberation in space, a carefree spirit.” — Andrew ‘Coco’ Coconato, Bob’s Dance Shop

If we’re being literal, the “Bob” comes from the name stitched into that original yellow bowling shirt, which sparked a fortuitous conversation. “I was doing client service work for this post-production company,” he explains. “And when I dropped coffee off to a client at an editing bay, he goes, ‘Hello Bob! What’s your story?’ Off the cuff, I just spitballed an improv, and stepped into this character: A gay choreographer from the South.”

Coincidentally, at the time, Coco was also looking to name a flash mob he was developing on the side. And so, a Flash Mob named Bob was born. And with it, an ethos. “Bob is an instant energy,” says Coco. “I call it the paradise for self-expression. You’re Bob, I’m Bob, we’re all Bob. It represents liberation in space, a carefree spirit.”

“Bob is an instant energy,” says Coco. “I call it the paradise for self-expression. You’re Bob, I’m Bob, we’re all Bob. It represents liberation in space, a carefree spirit.”

In addition to designing dance routines for feel-good viral videos, Bob’s Dance Shop organizes participatory flash mobs — or Flash Bobs — with tickets sold through Eventbrite. Purchasing one gets you an address to a rehearsal location where you’ll spend a few hours learning simple and fun choreography, plus the fine art of implementing the element of surprise.

You’ll perform for unsuspecting spectators, flash mob-style, and be filmed for a video by Coco’s Twisted Oak production crew. Because sure, doing this unique, joyful, and ultimately ephemeral thing is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. But if there’s no evidence to show your family and friends, did it really happen?

Flash Bob Miami, Bob’s Dance Shop. Photography by Aram Event Photography.

From a single mob to many

That first 2017 flash mob video led to Coco developing more characters in his arsenal who would ultimately see the spotlight: Rico, Donny, Hans, about 12 in all, each a distinct genre and color palette. “They’re like a diary,” says Coco.

“They’re like a diary,” says Coco.

Creating them allowed Coco to flex his filmmaking muscles, but there was one hitch: they weren’t making money. And to reach the goal of Twisted Oak independently producing short films and videos, they, well, needed money.

Coco decided that Bob, the soft-spoken choreographer and lover of flash mobs, would be the beacon to guide the way forward. He registered the name Bob’s Dance Shop (“because that’s what was available on Instagram and GoDaddy”) and started offering ticketed dance classes in studios.

“I would just pop up at a location, and I announced it on my Instagram,” he says. And he would teach whoever showed up an original dance routine. He then posted irreverent, easily replicable dance moves from the classes to his Instagram: the “candle wick,” the “airplane,” always with the hashtag #goodvibesonly. Anyone was invited to join, regardless of talent. In fact Coco doesn’t actually have any formal dance training himself — the moves come from a desire to express where the music takes him. However, a positive attitude was a must. “It was a very unique experience,” he says. “It looks a lot like what I’m doing right now, but at the time when I first started, it was just me. That was December of 2019, for perspective.”

However, a positive attitude was a must. “It was a very unique experience,” he says. “It looks a lot like what I’m doing right now, but at the time when I first started, it was just me. That was December of 2019, for perspective.”

And then the pandemic hit.

A phenomenon born in streaming

Lockdown understandably put a damper on the in-person classes. “I thought: Okay, well I can’t pop up in a studio. I need to take this virtual,” said Coco. He enlisted his roommates at the time, Jake and Lucas, and in March 2020, they produced their first class on Instagram Live. “It was fun, it was lighthearted. It was free.” And most importantly, everyone involved was smitten.

They started teaching weekly, and in between classes made dance videos of their own, pouring resources into slick productions. One of them, Tondo, caught the eye of none other than Google, who used it in an ad. “That gave me a confidence boost,” says Coco. “And confidence goes a long way.”

Then came viral hits. About a month after their big Google break, the Bobs re-made a dance challenge to “Pump Up the Jam.”

“It was so viral people thought we created the dance,” says Coco. Then a Mean Girls remake in Beverly Hills. The audience grew exponentially — people recreated their dances all around the world, from restaurant staff to flight crews to weddings, and there was even one request for them to flash mob a funeral. And then in June of 2021, the mask mandate was lifted in LA.

A return to their roots

The game was on. After months of being cooped up it was time to do another flash mob in person. “I put out an invite on Eventbrite, told a bunch of friends about it, and posted it on social,” said Coco. “Fathers got in free.” Fifty people showed up to mob Ocean View Park in Santa Monica.

On the gentle slope of the park, on a warm solstice day, it came together like a scene out of a movie. Spectators on picnic blankets clapped, mimicked hand gestures, and some even got up and joined in. “It wasn’t just us performing. Now these random people who didn’t even know who we were are now dancing with us,” says Coco.“It was pure joy. We were outside. And it just felt like the love was in the air.”

Spectators on picnic blankets clapped, mimicked hand gestures, and some even got up and joined in. “It wasn’t just us performing. Now these random people who didn’t even know who we were are now dancing with us,” says Coco.“It was pure joy. We were outside. And it just felt like the love was in the air.”

Coco posted the video and checked it before he went to bed. Within a few hours, it had a couple million views. The next morning it was up to eight or nine million. “It was everywhere,” he said. “I think it was just this perfect ingredient of people finally feeling free to just be social and to dance again, and to see it emanating so purely on a screen. They could feel the energy, even through an iPhone.”

The future of flash

Since then, Bob’s Dance Shop has taken their flash mobs from San Francisco to San Diego and Venice Beach to New York. They’ve mobbed red carpets (commissioned, don’t worry), and traveled around the UK on a sponsored tour, though they’ve learned that next time, they won’t give tickets away for free (“I learned it isn’t actually that effective because people don’t fully commit when there’s a free ticket”). They’ve even mobbed Buckingham Palace — but sadly got no outward acknowledgement from the guards (they were probably delighted though).

They’ve even mobbed Buckingham Palace — but sadly got no outward acknowledgement from the guards (they were probably delighted though).

“Bob is the sun to my solar system. It’s the main source of energy and light that gives life to all the other planets.” — Coco

And people can’t get enough. They’ve now moved into a new dimension: flash mobbing concerts and festivals, enlisted to create a “flash mob inception” for the band Sophie Tukker (being “pulled” from the audience on stage, then flash mobbing the crowd). Lollapalooza gave them their own stage, as did Austin City Limits. There are more on the horizon — just check their website. They plan to eventually incorporate a live band and original music.

But they will always return to their roots: a Flash Mob named Bob.

“Bob is the sun to my solar system. It’s the main source of energy and light that gives life to all the other planets,” says Coco. Next up, the plan is to build their own studios for dance classes. But until then, you can find them on the Internet. Or maybe on stage at your next music festival.

But until then, you can find them on the Internet. Or maybe on stage at your next music festival.

Interested in joining one of Coco’s flash mobs? Follow Bob’s Dance Shop on Eventbrite to be alerted when new events are added.

Up next: Read our creator spotlight on How One Concert Promoter Found Success in the Little Things.

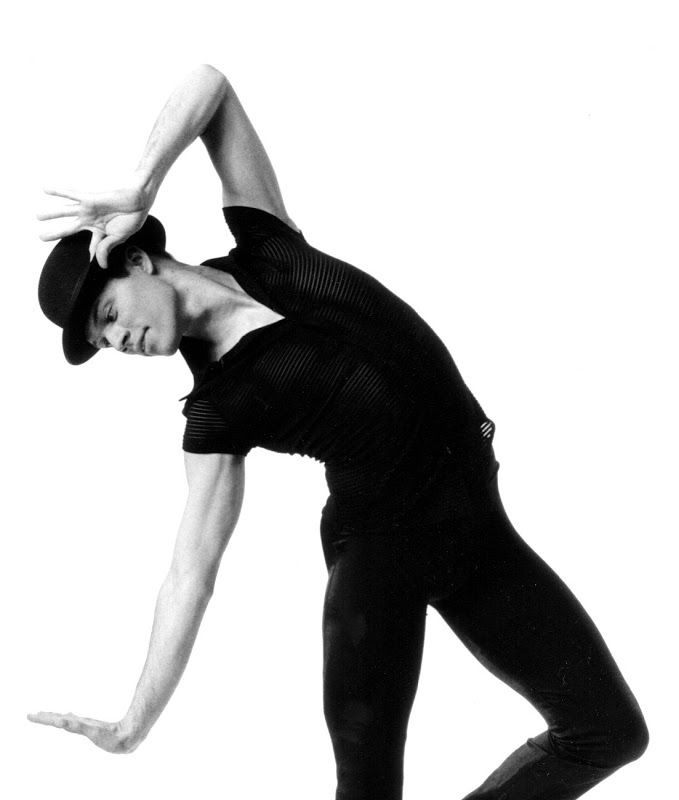

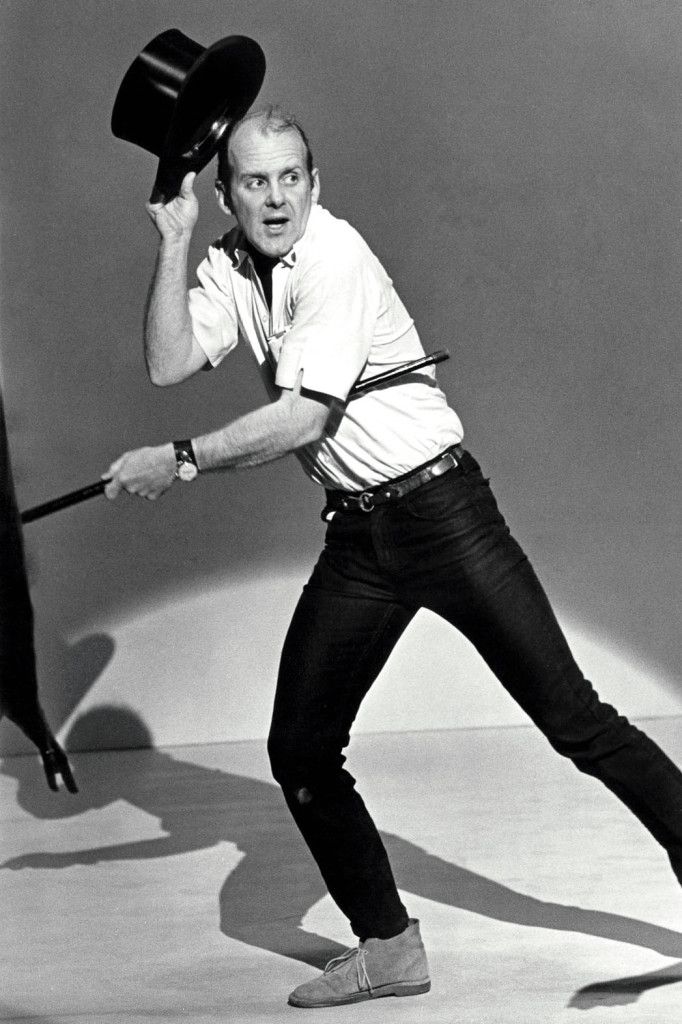

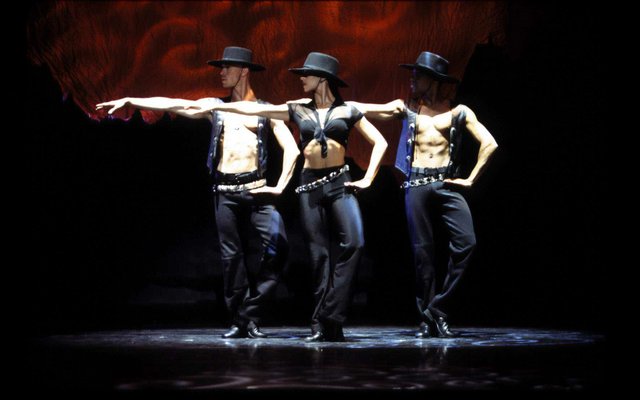

Bob Fosse | The Stars | Broadway: The American Musical

Director-choreographer Bob Fosse forever changed the way audiences around the world viewed dance on the stage and in the film industry in the late 20th century. Visionary, intense, and unbelievably driven, Fosse was an artist whose work was always provocative, entertaining, and quite unlike anything ever before seen. His dances were sexual, physically demanding of even the most highly trained dancers, full of joyous humor as well as bleak cynicism — works that addressed the full range of human emotions. Through his films he revolutionized the presentation of dance on screen and paved the way for a whole generation of film and video directors, showing dance through the camera lens as no one had done before, foreshadowing the rise of the MTV-era of music video dance.

Robert Louis Fosse was born in Chicago, Illinois, on June 23, 1927. Bob was the youngest of six children and quickly learned to win attention from his family through his dancing. It was not long before he was recognized as a child prodigy. His parents sent him to formal lessons, where he immersed himself in tap dancing. A small boy who suffered from nagging health problems, he nevertheless was so dedicated that by the time he reached high school, he was already dancing professionally in area nightclubs as part of their sleazy vaudeville and burlesque shows. The sexually free atmosphere of these clubs and the strippers with whom Fosse was in constant contact made a strong impression on him. Fascinated with vaudeville’s dark humor and teasing sexual tones, he would later develop these themes in his adult work. After high school, Fosse enlisted in the Navy in 1945. Shortly after he arrived at boot camp, V-J day was declared, and World War II officially came to an end. Fosse completed his two-year duty and moved to New York City.

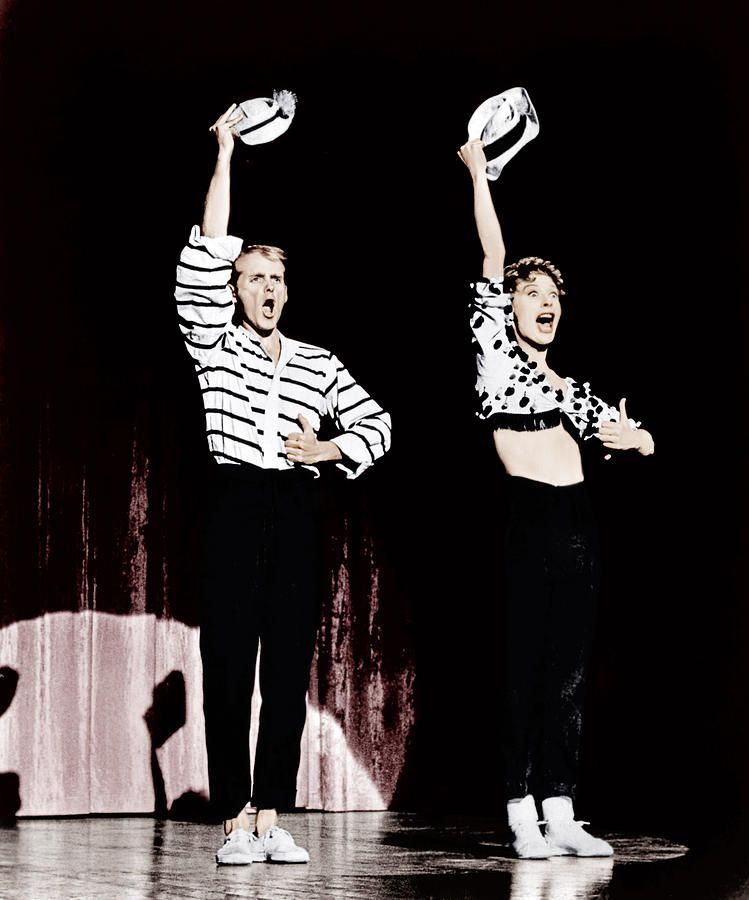

For the next seven years, Fosse went through two rocky marriages with dancers Mary Ann Niles and Joan McCracken, all the while performing in variety shows on stage and on television. He had a few minor Broadway chorus parts, but his big break came with his brief appearance in the 1953 MGM movie musical KISS ME, KATE. Fosse caught the immediate attention of two of Broadway’s acknowledged masters: George Abbott and Jerome Robbins.

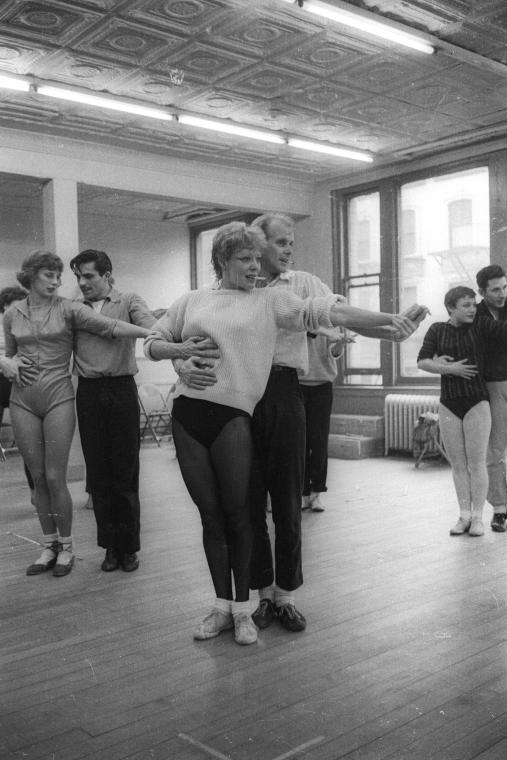

Bob Fosse rehearsing with dancers.

Fosse’s first fully choreographed show was 1954’s “The Pajama Game.” Directed by Abbott, the show made Fosse an overnight success and showcased his trademark choreographic style: sexually suggestive forward hip-thrusts; the vaudeville humor of hunched shoulders and turned-in feet; the amazing, mime-like articulation of hands. He often dressed his dancers in black and put them in white gloves and derbies, recalling the image of Charlie Chaplin. He incorporated all the tricks of vaudeville that he had learned — pratfalls, slights-of-hand, double takes. Fosse received the first of his many Tony Awards for Best Choreography for “The Pajama Game.”

Fosse received the first of his many Tony Awards for Best Choreography for “The Pajama Game.”

His next musical, “Damn Yankees,” brought more awards and established his life-long creative collaboration with Gwen Verdon, who had the starring role. With her inspiration, Fosse created a stream of classic dances. By 1960, Fosse was a nationally known and respected choreographer, married to Verdon (by then a beloved Broadway star) and father to their child Nicole. Yet Fosse struggled with many of his producers and directors, who wished him to tone down or remove the “controversial” parts of his dances. Tired of subverting his artistic vision for the sake of “being proper,” Fosse realized that he needed to be the director as well as the choreographer in order to have control over his dances.

His dances were sexual, physically demanding of even the most highly trained dancers.

From the late 1960s to the late 1970s, Fosse created a number of ground-breaking stage musicals and films. These works reflected the desire for sexual freedom that was being expressed across America and were huge successes as a result. Before Fosse, dance was always filmed either in a front-facing or overhead view. In his 1969 film version of SWEET CHARITY (Fosse’s 1966 stage version was based on an earlier movie by Italian director Federico Fellini, about a prostitute’s search for love; the film was commissioned by Universal Studios after the success of the stage version) and in later works, Fosse introduced unique perspective shots and jump cuts. These film and editing techniques would become standard practice for music video directors decades later.

These works reflected the desire for sexual freedom that was being expressed across America and were huge successes as a result. Before Fosse, dance was always filmed either in a front-facing or overhead view. In his 1969 film version of SWEET CHARITY (Fosse’s 1966 stage version was based on an earlier movie by Italian director Federico Fellini, about a prostitute’s search for love; the film was commissioned by Universal Studios after the success of the stage version) and in later works, Fosse introduced unique perspective shots and jump cuts. These film and editing techniques would become standard practice for music video directors decades later.

Bob Fosse

Born: June 23, 1927

Died: September 23, 1987

Key Shows

- "Bells Are Ringing"

- "Big Deal"

- "Chicago"

- "Damn Yankees"

- "Little Me"

- "New Girl in Town"

- "The Pajama Game"

- "Pippin"

- "Redhead"

- "Sweet Charity"

Related Artists

- Joel Grey

- Kander and Ebb

- Frank Loesser

- Donna McKechnie

- Robert Morse

- Bebe Neuwirth

- Jerry Orbach

- Harold Prince

- John Raitt

- Ann Reinking

- Chita Rivera

- Jerome Robbins

- Jule Styne

- Gwen Verdon

- Ben Vereen

- Tony Walton

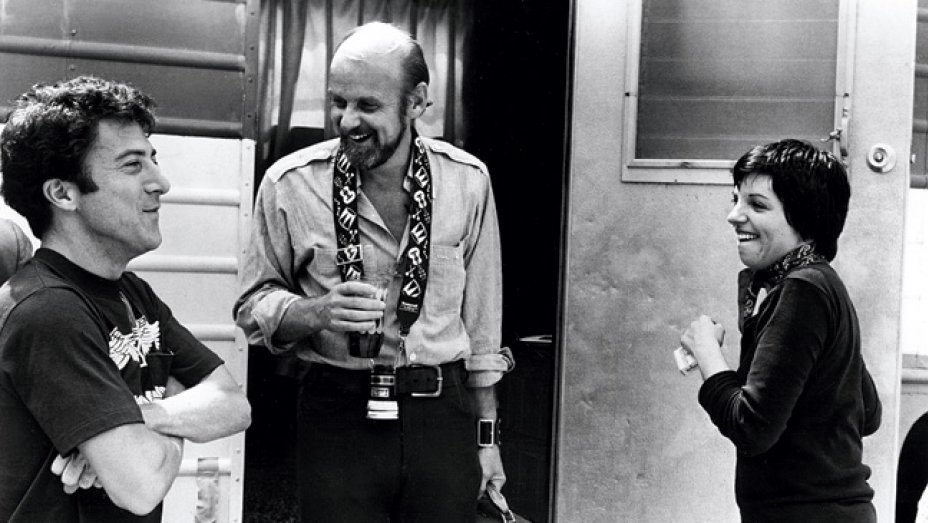

His 1972 film CABARET was based on Christopher Isherwood’s stories of pre-Weimar Germany. Articles on the film appeared in all the major magazines. Photos appeared on the covers of TIME and NEWSWEEK. The film was Fosse’s biggest public success and won eight Academy Awards. Fosse’s “Pippin” (1972) became the highest earning Broadway show in history, as well as the first Broadway show to advertise on national television. “Pippin” was awarded five Tony Awards for the 1972-73 season, one of them given to Fosse for best direction and choreography. Fosse staged and choreographed a variety show special for NBC starring Liza Minnelli, LIZA WITH A Z, which brought Fosse an Emmy Award and made him the first person to ever win top honors in three entertainment mediums — stage, film, and television.

Articles on the film appeared in all the major magazines. Photos appeared on the covers of TIME and NEWSWEEK. The film was Fosse’s biggest public success and won eight Academy Awards. Fosse’s “Pippin” (1972) became the highest earning Broadway show in history, as well as the first Broadway show to advertise on national television. “Pippin” was awarded five Tony Awards for the 1972-73 season, one of them given to Fosse for best direction and choreography. Fosse staged and choreographed a variety show special for NBC starring Liza Minnelli, LIZA WITH A Z, which brought Fosse an Emmy Award and made him the first person to ever win top honors in three entertainment mediums — stage, film, and television.

Two stage musicals followed: “Chicago” (1975) and “Dancin'” (1978). During rehearsals for “Chicago,” Fosse suffered a heart attack. He survived and used much of that traumatic experience in 1979 in his semiautobiographical dance film ALL THAT JAZZ. Two other films, LENNY (1974) and STAR 80 (1983), were not the popular successes that his other shows had been. “Big Deal,” Fosse’s last musical, was also poorly received. After a rehearsal for the revival of “Sweet Charity,” Fosse suffered a massive heart attack and died on the way to the hospital. Fosse’s contribution to American entertainment continued after his death via show revivals and dance classes. His most prominent contribution was through the body of his work recorded on film and video.

“Big Deal,” Fosse’s last musical, was also poorly received. After a rehearsal for the revival of “Sweet Charity,” Fosse suffered a massive heart attack and died on the way to the hospital. Fosse’s contribution to American entertainment continued after his death via show revivals and dance classes. His most prominent contribution was through the body of his work recorded on film and video.

Source: Excerpted from ST. JAMES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE. 5 VOLS., St. James Press, © 2000 St. James Press. Reprinted by permission of The Gale Group.

Photo credits: Photofest and the New York Public Library

Watch Gravity Less online video in good quality. 🚀 👍 Subscribe also to my other channels: ✅ 🌟 My telegram channel 🌟 ► https://t.me/GravityLess ✅ 🌟 Vkontakte 🌟 ► https://vk.com/GravityLess ✅ 🌟 Yandex Zen 🌟 ► https://zen.yandex.ru/GravityLess ✅ 🌟 YouTube channel 🌟 ► https://youtube.com/c/GravityLess7 ✅ ♛ NFT platform OPENSEA ♛ ► https://opensea.io/GravityLess ✅ ♚♚♚ Last. fm channel ♚♚♚ ► https://last.fm/ru/user/Andreyy1024 Shuffle, Sponge Bob, Running Men, Spin, Happy Fit, Kick, The V, shishkin's ponds, shuffle dancing, download sponge, shishkin forest, sponge bob square pants, Shuffle, Spongebob, Running Man, Spin, Happy Fit, Kick, V, 2019, 2020, 2021 #Elabuga #DANCE #Shuffle #SpongeBob #RunningMen #Spin #HappyFit #Kick #TheV #Shuffle #SpongeBob #SquarePants #RunningMan #Spin #HappyFit #Kick #V #2K11 #2K19 #ShishkinPonds #Park #Summer, #Spring, #Summer, #Spring, #PREMIERE, #Russia, #RF, shishkin's ponds, shuffle dancing, download sponge, shishkin forest, spongebob square pants shuffle dance shuffle dance best shuffle, shuffle dance training for beginners, shuffle video training, shuffle dance video training, shuffle school, how to dance shuffle for beginners, shuffle dance for beginners, how to learn shuffle, shuffle training, shuffle lessons, shuffle training for beginners, shuffle best, shuffle lessons, moscow, fast dance, shuffle dance video, shuffle lesson, music shuffle dance, electro shuffle, dance tutorial, edm dancing, top 10 shuffle moves, tik tok dancing, shuffle dance music, tik tok tutorial dance, tik tok dance, chinese shuffle, shuffle music, shuffle tutorial, shuffle bundle, shuffle dance 2021Ivanov, dancing from tik tok, how to learn to dance, dance lessons, shuffle learn, entertainment, tutorial, tik tok, shuffledance, shuffle girl, dancing on tnt, shuffle girls, house, shuffle house, steps, shuffle dance tutorial, how to dance for a guy , best dance, vibes, beautiful dances, how to dance in a club, girls dance cool, music, fashionable dance, top video, cool dance, dance video, cool dancing, children's dances, edm, shuffle movement tutorial, shuffle dance training, video from tik tok, children, shuffle child, dancing 2022, a$ap ferg feat.

fm channel ♚♚♚ ► https://last.fm/ru/user/Andreyy1024 Shuffle, Sponge Bob, Running Men, Spin, Happy Fit, Kick, The V, shishkin's ponds, shuffle dancing, download sponge, shishkin forest, sponge bob square pants, Shuffle, Spongebob, Running Man, Spin, Happy Fit, Kick, V, 2019, 2020, 2021 #Elabuga #DANCE #Shuffle #SpongeBob #RunningMen #Spin #HappyFit #Kick #TheV #Shuffle #SpongeBob #SquarePants #RunningMan #Spin #HappyFit #Kick #V #2K11 #2K19 #ShishkinPonds #Park #Summer, #Spring, #Summer, #Spring, #PREMIERE, #Russia, #RF, shishkin's ponds, shuffle dancing, download sponge, shishkin forest, spongebob square pants shuffle dance shuffle dance best shuffle, shuffle dance training for beginners, shuffle video training, shuffle dance video training, shuffle school, how to dance shuffle for beginners, shuffle dance for beginners, how to learn shuffle, shuffle training, shuffle lessons, shuffle training for beginners, shuffle best, shuffle lessons, moscow, fast dance, shuffle dance video, shuffle lesson, music shuffle dance, electro shuffle, dance tutorial, edm dancing, top 10 shuffle moves, tik tok dancing, shuffle dance music, tik tok tutorial dance, tik tok dance, chinese shuffle, shuffle music, shuffle tutorial, shuffle bundle, shuffle dance 2021Ivanov, dancing from tik tok, how to learn to dance, dance lessons, shuffle learn, entertainment, tutorial, tik tok, shuffledance, shuffle girl, dancing on tnt, shuffle girls, house, shuffle house, steps, shuffle dance tutorial, how to dance for a guy , best dance, vibes, beautiful dances, how to dance in a club, girls dance cool, music, fashionable dance, top video, cool dance, dance video, cool dancing, children's dances, edm, shuffle movement tutorial, shuffle dance training, video from tik tok, children, shuffle child, dancing 2022, a$ap ferg feat. nicki minaj, shuffle dance training, plain jane (alper karacan remix), popular songs remixes 2022, best remixes 2022, electro music, electro house mix, 24/7 live stream music, shuffle dance mix, electro dance 2022, happy feet, dancing feet, remixes of popular songs, learn to dance shuffle, tiktok dance, dance boy, children's choreography, trends, online school, dance training for girls, dance training for beginners, shuffle video, shuffle dance training, tiktok, bounce music, dance training from tik tok, shuffle dance 2022, learn shuffle, training, kids dance cool, home workouts, bass boosted, dancing at 60, dance training from scratch, dance training for adults, melbourne shuffle, shuffletutorial, tik tok, shuffle lessons, prkpkshuffle, dance training , melbourne bounce mix, dancing for weight loss, shuffle lesson 1, workout at home, get high, buoy buoy buoy, kuzmenok alexander, super dances, synchronized shuffle, whole spring, shuffle choreography, clips, kippy, gr tristar, shuffle dancing, georgy bryazgin, youtube shorts video, top, popular dance, shuffle tutorial, cool dances from tik tok, shaffle, shafl, prkpk, millenium dance centre, 1 million dance, dance moves, kiev dance, simple moves, new video, movies, movie dance tutorial, cool moves, shuffle, foot movements, shuffle, video lesson, shuffler, youtube shorts, shorts, dance dag , basic shuffle dance movements, shuffle dance, shuffle dance school, shuffle dance, cbd, kabardino balkaria, shuffle kiev, shuffle kiev, #shorts, how to, how to shuffle dance, chapkis dance, ukranian dance, fortnight, dancing at 50, america, kazakhstan, movements, lezginka, cool, fortnite dancing, dancer, salam alaikum brothers, melbourne bounce, remix, bounce party dance mix, shuffle dance (music video), melbourne bounce music mix 2017, mihran kirakosian, gaming mix, alan walker , faded shuffle, house dance, dance music, elec tro 2016, electro dance, electro, electro house, beautiful shuffle dances, shuffle dance music video, evelina khromtchenko, alexander vasiliev, fashion, nadezhda babkina, elina zikeyeva, grandfather, shuffle princess, style, trendy, shuffle man, the couple is dancing cool, dina denisova, pioneer, fashion verdict, pionerka, electro house dance, shuffeln, tuzelity, tuzelity, watch to the end, simp, in a club, tutorial, dancing best, super video, cool dancing, cool video, 9halls, team, super dance, cool dances, contagious dancing

nicki minaj, shuffle dance training, plain jane (alper karacan remix), popular songs remixes 2022, best remixes 2022, electro music, electro house mix, 24/7 live stream music, shuffle dance mix, electro dance 2022, happy feet, dancing feet, remixes of popular songs, learn to dance shuffle, tiktok dance, dance boy, children's choreography, trends, online school, dance training for girls, dance training for beginners, shuffle video, shuffle dance training, tiktok, bounce music, dance training from tik tok, shuffle dance 2022, learn shuffle, training, kids dance cool, home workouts, bass boosted, dancing at 60, dance training from scratch, dance training for adults, melbourne shuffle, shuffletutorial, tik tok, shuffle lessons, prkpkshuffle, dance training , melbourne bounce mix, dancing for weight loss, shuffle lesson 1, workout at home, get high, buoy buoy buoy, kuzmenok alexander, super dances, synchronized shuffle, whole spring, shuffle choreography, clips, kippy, gr tristar, shuffle dancing, georgy bryazgin, youtube shorts video, top, popular dance, shuffle tutorial, cool dances from tik tok, shaffle, shafl, prkpk, millenium dance centre, 1 million dance, dance moves, kiev dance, simple moves, new video, movies, movie dance tutorial, cool moves, shuffle, foot movements, shuffle, video lesson, shuffler, youtube shorts, shorts, dance dag , basic shuffle dance movements, shuffle dance, shuffle dance school, shuffle dance, cbd, kabardino balkaria, shuffle kiev, shuffle kiev, #shorts, how to, how to shuffle dance, chapkis dance, ukranian dance, fortnight, dancing at 50, america, kazakhstan, movements, lezginka, cool, fortnite dancing, dancer, salam alaikum brothers, melbourne bounce, remix, bounce party dance mix, shuffle dance (music video), melbourne bounce music mix 2017, mihran kirakosian, gaming mix, alan walker , faded shuffle, house dance, dance music, elec tro 2016, electro dance, electro, electro house, beautiful shuffle dances, shuffle dance music video, evelina khromtchenko, alexander vasiliev, fashion, nadezhda babkina, elina zikeyeva, grandfather, shuffle princess, style, trendy, shuffle man, the couple is dancing cool, dina denisova, pioneer, fashion verdict, pionerka, electro house dance, shuffeln, tuzelity, tuzelity, watch to the end, simp, in a club, tutorial, dancing best, super video, cool dancing, cool video, 9halls, team, super dance, cool dances, contagious dancing

PERIOD OF CREATIVE INTERACTION WITH PAUL TAYLOR POSTMODERN DANCE: A PERIOD OF CREATIVE INTERACTION WITH PAUL TAYLOR

Yu. O. Novik, SV Lavrova1

O. Novik, SV Lavrova1

1 A.Ya. Vaganova, st. Architect Rossi, 2, St. Petersburg, 191023, Russia.

The article recreates the history of creative interaction between two well-known figures of American artistic culture — the artist Robert Rauschenberg and the dancer Paul Taylor — involved in the development of postmodern dance in America in the 1940s-1960s. Facts are presented, motivation is investigated, worldview positions are compared, cases of coincidence and discrepancy between the goals and objectives of creativity, solved by Rauschenberg and Taylor together and separately, are described. The main projects (theatrical and dance performances) implemented jointly are listed, the most significant results of Rauschenberg's co-creation with Taylor are characterized.

Keywords: postmodern dance, Robert Rauschenberg, Paul Taylor, modern choreographic art.

BOB RAUSCHENBERG IN THE HISTORY OF POSTMODERN DANCE: A PERIOD OF COLLABORATIONS WITH PAUL TAYLOR

Novik Yu. O., Lavrova S. V.1

O., Lavrova S. V.1

1 Vaganova Ballet Academy, Rossi St., 2, Saint-Petersburg, 191023, Russian Federation.

The article reconstructs the story of the creative interaction of two famous figures of American art culture - artist Robert Rauschenberg and dancer Paul Taylor - who were involved in the establishment of postmodern dance in America in the 1940-1960s. The facts are stated, motivation is investigate, worldview positions are compared, cases of coincidence and mismatch of the goals and tasks of creativity, solved by Rauschenberg and Taylor together and separately, are described. The main projects (theater and dance performances) implemented jointly are listed; the characteristic of the most significant results of the co-creation of Rauschenberg with Taylor is given.

Keywords: postmodern dance, Robert Rauschenberg, Paul Taylor, contemporary choreographic art.

The work of the famous American artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), one of the leading representatives of neo-Dadaism, is borderline. It does not fit into the "Procrustean bed" of clear stylistic definitions. The artist in every possible way denied any specific hierarchy and genre boundaries of art. He worked in a variety of techniques of painting, graphics and arts and crafts, creating objects and installations, ready-mades and collages in the style of junk art from traditional (primarily paints) and non-traditional (“things from the trash can”) materials1 , was engaged in lighting design, media art, theatrical scenery and costumes, was seriously interested in choreography, and even wrote music.

It does not fit into the "Procrustean bed" of clear stylistic definitions. The artist in every possible way denied any specific hierarchy and genre boundaries of art. He worked in a variety of techniques of painting, graphics and arts and crafts, creating objects and installations, ready-mades and collages in the style of junk art from traditional (primarily paints) and non-traditional (“things from the trash can”) materials1 , was engaged in lighting design, media art, theatrical scenery and costumes, was seriously interested in choreography, and even wrote music.

It was the interest in choreography, postmodern dance that prompted Rauschenberg to leave the somewhat closed community of abstract artists and enter a much wider creative circle of American choreographers, composers, dancers and musicians. Postmodern dance made the space resonate in the paintings of Rauschenberg, breathed life into the art objects he created.

Rauschenberg's ideas about postmodern dance (its philosophy, psychology, technical capabilities, etc. ) were constantly changing. The artist's attitude to choreography was formed and evolved in the conditions of creative interaction with the icons of several generations of postmodern dance, including Paul Taylor. Together with this first-generation professional, he created and put into practice the idea, revolutionary for those years, of the absolute identity of any human movements with dance movements. At the same time, each time, implementing this or that joint project, the co-authors strove for a common goal: to eliminate the artificial barriers between art and life that have been established for centuries.

) were constantly changing. The artist's attitude to choreography was formed and evolved in the conditions of creative interaction with the icons of several generations of postmodern dance, including Paul Taylor. Together with this first-generation professional, he created and put into practice the idea, revolutionary for those years, of the absolute identity of any human movements with dance movements. At the same time, each time, implementing this or that joint project, the co-authors strove for a common goal: to eliminate the artificial barriers between art and life that have been established for centuries.

Black Mountain College

Rauschenberg made his first steps towards choreographers and postmodern dancers as a student at Black Mountain College of Art in North Carolina. Founded in the midst of the American economic depression (in 1933), educational institution

1 The British art historian Lawrence Alloway, the author of the term-definition "junk art" (from the English junk - rubbish, rubbish), considered it ideally suited to characterize the specifics of the creative method of R. Rauschenberg.

Rauschenberg.

strived for fame, public recognition, achievement of the highest, in terms of real and potential employers, the results of pedagogical and artistic and professional activities of teachers and graduates. For these reasons, the college was open to revolutionary artistic experimentation in dance, music, visual arts, and literature.

Rector John Andrew Rice, artist Josef Albers2 and poet Charles Olson made the greatest contributions to this unique educational project. Celebrities taught at the school: composer John Cage, choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham, artist Robert Motherwell, a married couple of artists (Willema and Elaine) de Kooning, poet and prose writer Robert Creeley, pianist and composer David Tudor and others. Teachers organized creative meetings of students with invited writers, choreographers, composers, plastic artists, creating an atmosphere of dialogue necessary for a free exchange of opinions, presentation of the results of specific creative practices.

Rauschenberg's acquaintance with the rising star of the American dance theater Merce Cunningham took place during the summer session of 1952, which was remembered by teachers and students of the school for the resonant production of John Cage's "Theater Piece No. 1". With her help, the author (composer and director of the production rolled into one) tried to convey to the audience the ideas of conceptualism, giving them the form of a staged conceptual event. Both spectators and artists who gathered at the same time and on the same stage became direct participants in the action.

The performers of the cage composition had to perform, or not to perform (inactive), some discrete actions aimed at sound extraction (such as: making speeches, playing musical instruments, dancing, walking ...), filling with them the time segments of the production. “My idea,” Cage explained, “was to try to treat objects, the various actions of artists, as sounds” (cited in: [2]). As a musician and composer, he was very interested in how these "sources of sound" could be multiplied. As for the narrowly professional tasks solved by the rest of the participants in the performance, they, of course, each had their own, but the idea

As for the narrowly professional tasks solved by the rest of the participants in the performance, they, of course, each had their own, but the idea

2 The pioneer of American abstract art, J. Albers, according to Rauschenberg, was his "excellent teacher", but an absolutely "impossible personality" [1].

"action-sounds", like some of Cage's other conclusions, gave rise to intellectual searches in "theatrical art forms" adjacent to music.

Rauschenberg, in particular, was extremely close to the cage theme of absolute "silence" in music, which the composer interpreted in the physical plane (not as "deafness" - the complete disconnection of a person's hearing aid from external stimuli (sound signals), but a deliberate switching of the psyche from the habitual perception of constant sounds to random ones). The teacher (Cage) and the student (Rauschenberg), each in their own way, tried to figure out what expressive means of music and painting could convey such silence.

Moving on his own (but, in fact, parallel to the Cage) course, Rauschenberg, at the very beginning of his career as an artist, came to the so-called "white" painting. His experimental painting practice was based on a set of intellectual reflections on the absolute whiteness (or emptiness) of a picture, in which an invisible Nothing could be hidden under an impenetrable film of white paint3.

From the descriptions of the performance4, which took place at Mountain Black College, it follows that Rauschenberg's participation in the compositions of the production was at the same time direct (“putting old records on the gramophone”, “showing rapidly flashing “abstract slides” and film frames” [3]) , and mediated by "white paintings", attached to the ceiling of the "auditorium" before the start of the performance.

“Rauschenberg's 'White Paintings' caught everything that fell into their field5,” Cage recalled. “There was no absolute silence or whiteness. However, the silence and whiteness made it possible to establish an extraordinary energetic connection with the listener, spellbound.

3 The concept of emptiness/whiteness was visualized by Rauschenberg in 1953. The demonstration of the concept product in the form of the painting “Erased drawing of de Kooning” was accompanied by a grandiose scandal, as the artist presented the audience with a blank canvas as his creation, “whitened” after removing the drawing originally applied to it by another well-known abstract artist at that time.

4 Roseley Goldberg used the characteristic "performance" in relation to the production.

5 Apparently, we are talking about the late technique of creating “white paintings”, notable for the fact that the painting was obtained by highlighting the canvases from the side of the audience. In this case, the shadows-ghosts cast by the bodies of the spectators lay on the white, creating the effect of the presence of the Invisible and the Phantom in it.

silence, and with the viewer observing the infinity of the white picture that goes beyond the frame” [4]. The compositions of Cage and Rauschenberg denied sound and color, but in order to understand this denial, one had to “turn on the imagination”, believe that the paths are open and everything is possible.

And essentially what Cage did for the discovery and intellectual interpretation of silence, Rauschenberg for emptiness or whiteness, Merce Cunningham did for stillness. Rauschenberg and Cunningham's most general conversations about post-modern dance also began at Black Mountain College, but it was not until Rauschenberg joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1955 that they became more concrete. costume designer and theater props designer. (Before that, Rauschenberg regularly attended rehearsals of the dance troupe, photographing artists during the preparation and conduct of performances. Many of Rauschenberg's photographs eventually became priceless and were used with pleasure by the organizers of the group's concert activities for advertising purposes.) From 1954 to 2007, Cunningham and Rauschenberg jointly created 23 theatrical productions.

Studying at Black Mountain College not only turned the young artists, poets, and representatives of other artistic professions who studied there into experts in their field, but contributed to the expansion of their general art criticism erudition. For example, teachers and students considered the problem of the language of theater art to be trans-professionally significant. “I have read Antonin Artaud,” Cage declared, “like him, I believe that the stage is a concrete physical space that needs to be filled and allowed to speak. I believe that this particular language of the stage, addressed to the senses and independent of the sounding word, should satisfy, first of all, the senses; that there is a poetry of the senses, just as there is a poetry of language; that particular physical language. is truly theatrical only when the thoughts it expresses elude ordinary language” (quoted from: [2, p. 57]).

For example, teachers and students considered the problem of the language of theater art to be trans-professionally significant. “I have read Antonin Artaud,” Cage declared, “like him, I believe that the stage is a concrete physical space that needs to be filled and allowed to speak. I believe that this particular language of the stage, addressed to the senses and independent of the sounding word, should satisfy, first of all, the senses; that there is a poetry of the senses, just as there is a poetry of language; that particular physical language. is truly theatrical only when the thoughts it expresses elude ordinary language” (quoted from: [2, p. 57]).

Innovative for performance, the idea of a separate action that fits into the same time and space was inextricably linked with the idea of stage space discreteness. Visualizing the latter, the organizers of the significant performance of 1952 divided the auditorium in which the play was played,

, into four triangles directed with their vertices towards the empty center (Fig. 1).

1).

Jllaefc Mountain

iriti und t9£l

1. Stage plan designed for John Cage's "Theatrical Play No. 1"

The new layout of the stage layout dispersed the seats for spectators as much as possible. In addition, the stage action should not have taken place exclusively in the center, but also in the distant parts of the auditorium: in four triangles with seats for spectators, in the aisles between them, and even at the top of the ceiling. Rauschenberg-Taylor53 year. Taylor was literally struck by the originality of the idea and the embodiment of the composition (“combination”) of earth, garbage and household rubbish collected by Rauschenberg near his place of residence on

6 Street. In 1953, Taylor danced in the young company of Merce Cunningham, but was about to leave it, because hatched plans to open his own business - the dance troupe of Paul Taylor.

Fulton: “It all seemed to me very beautiful, mysterious, darkly comical, but at the same time somewhat atavistic,” Taylor recalled (cited in: [5]). As it soon became clear, both were attracted by the prospect of creating works of art with "elements of everyday life." Both sought, on the one hand, to bring an element of naturalness into the world of art, on the other hand, to show their positive, but at the same time ironic, attitude of artists to everyday life7.

As it soon became clear, both were attracted by the prospect of creating works of art with "elements of everyday life." Both sought, on the one hand, to bring an element of naturalness into the world of art, on the other hand, to show their positive, but at the same time ironic, attitude of artists to everyday life7.

Acquaintance was secured by an agreement: Taylor asked the artist to design sets and costumes for his debut choreographic production of "Jack and the Beanstalk" (Jack and the Beanstalk). The performance, which was performed only once in 1954, was defined by Taylor himself as a "non-narrative fairy tale" [5], in which discrete poses, borrowed from book illustrations, were devoid of narrative connection and, in essence, replaced the story. With his work, he challenged Martha Graham, who still connected the prospects for the development of American choreography with the once revolutionary, abolishing the forms of classical ballet and modernizing the content of world choreography, modern dance. Taylor believed that this time the famous dancer did not have enough subtlety of flair to understand that modern dance had come close to the next line of development, beyond which deep transformations began, associated with the transformation of plot art into abstract form-creation. In the case of postmodern dance, “dance should not have any “plot”, should not “tell” anything. Moreover, the dance should not "express" anything. The content of the dance should be the dance itself. If he talks about anything, it is about the body of a dancing person” [6, p. 172]. So thought Taylor, Cunningham and many other dancers who left the Graham Company in the middle of the 1950s.

Taylor believed that this time the famous dancer did not have enough subtlety of flair to understand that modern dance had come close to the next line of development, beyond which deep transformations began, associated with the transformation of plot art into abstract form-creation. In the case of postmodern dance, “dance should not have any “plot”, should not “tell” anything. Moreover, the dance should not "express" anything. The content of the dance should be the dance itself. If he talks about anything, it is about the body of a dancing person” [6, p. 172]. So thought Taylor, Cunningham and many other dancers who left the Graham Company in the middle of the 1950s.

Rauschenberg subtly caught the rebellious mood of the director of the performance. He himself rebelled against abstract expressionism, which literally crushed the American painters of the new generation with its authority, having developed, as a universal antidote to the abstractness of abstractionism, a method of introducing real objects and images of symbols into paintings and scenery. For registration

For registration

7 “He jumped over the tediousness of mechanical conveyor production, allowing himself the luxury of understanding art as a child's game,” our compatriot E. Yevtushenko gave such an assessment of Rauschenberg's work [1].

of Taylor's "non-narrative fairy tale", for example, Rauschenberg used a toy as an "element of everyday life" - a balloon on a rope - an amazing and at the same time banal substitute for the image of a magical plant. In this and subsequent stage productions, Rauschenberg's visuals, bright in their minimalist expressiveness, turned out to be equivalent to Taylor's choreography.

Once in the theater, Rauschenberg discovered not only the space of the stage, but also other corners of the theater (proscenium, backstage), which he did not fail to tell not only to visitors to Taylor's theatrical productions, but also to his own exhibitions of paintings and combinations. He opened closed invisible doors, broke partitions, and placed objects behind the scenes that became the basis of his artistic tools: stairs, fire equipment, chairs, bicycles, wheels, etc. , elementary scenery used as theatrical props and household items. However, experiments with household items began long before that. While performing at Dartington College of Art in Devon, Rauschenberg and Alex Hay introduced the ironing board and iron into the performance.

, elementary scenery used as theatrical props and household items. However, experiments with household items began long before that. While performing at Dartington College of Art in Devon, Rauschenberg and Alex Hay introduced the ironing board and iron into the performance.

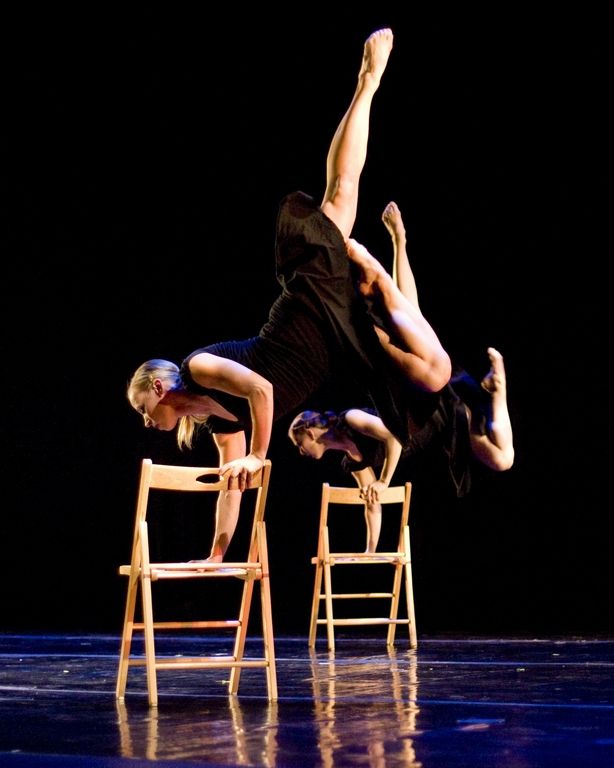

The next collaboration between the artist and the dancer, the performance Three Epitaphs (Three Epitaphs, 1956), by its belonging to the New Orleans-specific dance-music genre of black dance comedy8, opened up scope for experimenting with stage costumes. For this production, Rauschenberg designed special costumes based on black tights with hoods, to which small round mirrors were attached at head level, capable of reflecting light during the movement of the dancers (Fig. 2).

8 A funeral ceremony in New Orleans is a special cultural tradition filled with the semantics of grief and hope at the same time. The movement of the funeral procession towards the cemetery to the funeral music of the brass band is the first part of the ritual of farewell to the deceased. The movement of people from the cemetery is the second, optimistic part of the tragedy. People returning from the funeral danced to make amends a little for their grief.

The movement of people from the cemetery is the second, optimistic part of the tragedy. People returning from the funeral danced to make amends a little for their grief.

)

Jf

h

> s

2. Dancers dressed as Rauschenberg. Performance "Three epitaphs"

The attire invented by the artist intentionally deprived the dancers of their individuality, as their faces were tightly covered with a knitted fabric. The black color added a certain amount of ethnic connotation to the clothes, indirectly pointing to the African-American roots of funeral dances.

In Three Epitaphs, Taylor took Rauschenberg's idea of kinetic space and recreated it on stage using mirrors. The choreographer strove for stinginess, stiffness of movements. According to Rauschenberg, when he realized that the choreographic solution looked embellished, he "switched Debussy's music to funeral jazz, which ensured the replacement of lyrical movements with lead" (quoted from: [7]).![]() After that, the dancers began to move slowly, moving their legs with difficulty: while waving their arms, the artists played with the light of the mirrors held in their palms.

After that, the dancers began to move slowly, moving their legs with difficulty: while waving their arms, the artists played with the light of the mirrors held in their palms.

The theme of urbanism came to the fore in Seven New Dances (1957). By means of dance, the director tried to tell the audience about the rhythms of the life of a big city: the movement of vehicles along the busy streets, the sidewalk movement of pedestrians, and even animals. Taylor's abstract dance found its heroes: casual passers-by hurrying to work, or, conversely, people walking slowly through the streets - men and women, old people and children.

The program began with Taylor's solo (a number called "Epic" - Epic), in which the dancer stood motionless, made the elementary movements necessary for walking: he stepped from foot to foot, squatted at the knees, walked, etc. On the performer there was no special theatrical costume. The dancer was dressed in an ordinary business men's suit and shod with boots.

One of the other numbers was a duet, the climax of a seven-part program, in which Taylor, still in his suit and tie, came on stage accompanied by a lady in a cocktail dress (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Dancers dressed as Rauschenberg.

Performance "Seven New Dances: Duet" The partner stood motionless in the center of the stage, and the partner sat at his feet, also without movement, for exactly four minutes. Then the curtain was closed.

In general, the work sent the prepared, i.e., more or less versed in the theory of postmodern, viewer to Rauschenberg's "White Canvases" (1951) and the Cage composition "4'33" (1952). The following "elements" of postmodern dance were explained to the inexperienced viewer:

- dance is any movement;

- a dancer's costume is any comfortable everyday work and/or home wear;

- props of a dance performance - this is everything that happened to be around the dancer at the time of the performance;

- dance music - these are the sounds of the environment in which the dancer found himself at the time of the performance.

Judging by the responses, the dancer's and artist's experiment in studying the expressive possibilities of everyday ("pedestrian") movements and the expressiveness of complete immobility was a success. Critics who had been "at a lesson" in postmodern dance, not without irony, responded to the event: Horst)" [6, p. 181].

By the 1960s, Taylor had lost interest in theatrical visualization of "pedestrian movements". This is evidenced by Tracer (1962), the last collaboration between Rauschenberg and Taylor to music by James Tenney, in keeping with the late Taylor style, which contains sublime ballet movements and the choreographer's musicality. Rauschenberg, at the same time, began to move rapidly in the opposite direction. As the inventor of "combined paintings", he could not help but react to the emergence of new technologies (for example, silk-screen printing, cotton, "gauze" printing, etc.) for creating works of fine art, not to try to introduce photographs, newspapers and other new items. At that time, he also worked a lot on the problem of creating and subject filling the stage space, in particular, he designed and manufactured, symbolizing the abundance of information in the modern world, “revolver” mills with plexiglass glass blades [7].

At that time, he also worked a lot on the problem of creating and subject filling the stage space, in particular, he designed and manufactured, symbolizing the abundance of information in the modern world, “revolver” mills with plexiglass glass blades [7].

For Tracer, Rauschenberg assembled a set of objects, including a remote-controlled bicycle wheel attached to a wooden base. It accompanied the dance with periodic rotations. The tracer wheel has become a kind of emblem of rhythm and mechanical movement (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Rauschenberg's tracer wheel

If in "white painting" Rauschenberg worked in the field of intellectual cage "silence", then in the case of the tracer, the "combine" he created was likened to a ready-made ("Bicycle wheel" by M. Duchamp (1913)).

Creatively interacting with Taylor, Rauschenberg fed on his plastic ideas, which he whimsically projected onto his own paintings and sculptures. Rauschenberg also had a reverse influence on Taylor. The latter was an adherent of constancy, but when Rauschenberg included everyday objects in the scenery and costumes, Taylor, in turn, "revived" them with simple gestures and elementary movements.

The latter was an adherent of constancy, but when Rauschenberg included everyday objects in the scenery and costumes, Taylor, in turn, "revived" them with simple gestures and elementary movements.

During the eight years of cooperation, the artist Raushenbegr and the dancer Taylor have implemented 17 joint dance and theater creative projects.

LITERATURE

1. Yevtushenko EA Bob Rauschenberg and the Frog Princess // Politics is the privilege of all. Journalism book. M.: Publishing House of APN, 1990. 624 p. [Electronic resource]. URL: http://padaread. com/?book=214273&pg=435-438 (accessed 09/01/2019).

2. Valdeira da Silva Vieira A.-L. Teoria da Relatividade Combinatoria Os Espectáculos de John Cage, Merce Cunningham e Robert Rauschenberg Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa 2011, 179 p.

3. Performance at Black Mountain College [Electronic resource]. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Performance_at_Black Mountain College (Date of access: 01.09.2019).

4. Cage J. Silence. Lectures and Writings 1973. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://monoskop.org/images/b/b5/Cage_John_Silence_Lectures_and_ Writings.pdf (accessed 09/01/2019).

Cage J. Silence. Lectures and Writings 1973. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://monoskop.org/images/b/b5/Cage_John_Silence_Lectures_and_ Writings.pdf (accessed 09/01/2019).

5. Harris J. Dance among Friends Robert Rauschenberg's Collaborations with Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham, and Trisha Brown [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/3441 (accessed 01.09.2019).

6. Surits E.Ya. Ballet and dance in America: Essays on history. Yekaterinburg: Publishing House Ural. University, 2004. 392 s.

7. Robert Rauschenberg: biography, works, photos [Electronic resource]. URL: https://fb.ru/article/250094/robert-raushenberg-biografiya-rabotyi-foto (date of access: 09/01/2019).

REFERENCES

1. Evtushenko E. A. Bob Raushenberg i czarevna-lyagushka // Politika - priv-ilegiya vsex. Book publicistics. M.: Izd-vo APN, 1990. 624 s. [E4ektronnyxj resources]. URL: http://padaread.com/?book=214273&pg=435-438 (data obrashheniya: 09/01/2019).

2. Valdeira da Silva Vieira A.-L. Teoria da Relatividade Combinatoria Os EspectÁculos de John Cage, Merce Cunningham e Robert Rauschenberg Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa, 2011. 179p.

Valdeira da Silva Vieira A.-L. Teoria da Relatividade Combinatoria Os EspectÁculos de John Cage, Merce Cunningham e Robert Rauschenberg Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa, 2011. 179p.

3. Performans v Ble'k Mauntin college [E4ektronnyxj resources]. URL: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Performans_v_Blexk-Mauntin-college (data obrashheniya: 09/01/2019).

4. Cage J. Silence. Lectures and Writings 1973. [E4ektronnyxj resurs]. URL: https://monoskop.org/images/b/b5/Cage_John_Silence_Lectures_and_ Writings.pdf (data obrashheniya: 09/01/2019).

5. Harris J. Dance among Friends Robert Rauschenberg's Collaborations with Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham, and Trisha Brown [E4ektronnyxj resurs]. URL: https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/3441 (data obrashheniya: 01.09.2019).

6. Suricz E. Ya. Ballet i tanecz v Amerike: Ocherki istorii. Ekaterinburg: Izd-vo Ural. Un-ta, 2004. 392 s.

7. Robert Raushenberg: biografiya, work\foto [E4ektronnyxj resources]. URL: https://fb.