How has belly dancing changed over the years

Belly dance History and origins, Turkey and Egypt. Raks sharqi.

The Terminology

The origin of the name ‘belly dance’ comes from the French Danse du ventre, which translates as “dance of the stomach”.

Sol Bloom is said to have been the first one to use the English term belly dance, for the dancers of the Chicago’s World Fair in 1893. Belly dance is also often referred to as “oriental dance” and also sometimes Raks sharqi.

This is Arabic for “Dance of the east”. The term Dance du ventre, from which belly dance originates, had originally racist connotations so there is currently a debate going on about whether the term belly dance should still be used.

According to some it should be avoided and replaced possibly with oriental dance, in order to dissociate this dance form from the misconceptions associated to it. According to others, the term belly dance is here to stay, it is the most known way of naming this dance form and it has now lost its racist connotations anyway.

The racist implications of the term belly dance are concerning, but I often find that, if I call it oriental dance, people think I am referring to dance of the Far East, from countries such as China, Korea or Japan.

The Arabic for oriental dance, raqs sharqi, seems lately to refer to one particular style, which does not include dances such as raqs shaabi, baladi or American tribal.

Andrea Deagon prefers to call this dance SITA (solo-improvised dance based on torso articulation).

While I like this term, I do not think that it is right for every type of what we call ‘belly dance’ as, for example, tribal is done in groups and also Raqs sharqi, when it is performed outside of its countries of origin, is sometimes performed in groups and to a choreography rather than being improvised.

Also, SITA could refer to many other dance forms that we would not consider ‘belly dance’, such as Moroccan Shikhat.

So, it is still hard, in my opinion, to define exactly what this dance genre includes.

Maybe we should not talk about ‘belly dance’ as one dance genre at all, but we should isolate different types of dance that so far have been bundled together, such as Raqs sharqi, American tribal, raqs baladi and saabi and so on and treat them as different genres which have some common roots.

Origins of the Dance

According to some, the dance form that today many call belly dance is extremely old and traces of it can be found up to 6,000 years ago, in some pagan societies who used to worship a feminine deity, to celebrate women’s fertility as something magic.

However, there is little evidence that early pagan rituals are in any way connected to belly dance.

This type of dance is supposed to be indeed good for preparing women’s body to give birth, but there does not seem to be proof of any link to ancient fertility rituals.

In spite of this, there has been a tendency, in the last 40 years, to associate belly dance with spirituality and the power of the feminine.

This may be due to the fact that the feminist movement, in the 1970s and 1980s in the USA, rediscovered belly dance as a form of dance that empowers women.

What we called today belly dance, seems to be the specific type of dance that comes from Turkey and Egypt.

By looking at the specific movements of belly dance, some say that there could have been an influence coming from India. Indeed some movements, such as the head slides, are found both in Indian dance and in belly dance.

Hence, it could be that populations migrating over the centuries from India to the Middle East and northern Africa brought their dance traditions with them, influencing the way local dances developed.

Also, I think that belly dance owns a lot, in terms of dance vocabulary, to African dances.

If we think about hip and chest shimmies and circles and body undulations, these are also present in African dances and in South American dances that derive from African traditions.

However, each dance tradition has changed and adapted these movements so that, for example, shimmies in belly dance have a different feeling from African shimmies.

A proper chronological and historical study of dance and movement should be done in order to confirm how and when these influences developed, but it is difficult for such an ephemeral product like dance.

Nevertheless, it could be attempted in the same way that linguists have studied the history of languages and traced migrations from ancient India to Europe with regards to the Indo-European languages, although movement did not leave a trace equivalent to written texts for languages.

This dance form, in the Middle East, has been a type of social dance since unmemorable times. It was and is danced when women gather together to socialize.

For example, my first belly dance teacher, whose family is from Iraq and Jordan, told me how, even today, women sometimes dance to it when they meet and also chose potential brides for their sons according to the way the girls dance.

In Egypt, dance has always been part of wedding celebrations, danced socially by people attending parties and professionally by performers who are paid to dance for special occasions.

This is the typical Baladi dance. Nowadays, the music played most commonly at weddings and social gatherings in Egypt is Shaabi.

The type of dance associated with shaabi music is very similar to baladi dance with hip articulations and quite grounded, but it does not have the same structure, as the music is different (shaabi music is composed by individual pop songs, while baladi is mainly instrumental music which is improvised but follows a set pattern, hence a baladi dance performance follows the same pattern translated into movement).

What we call today belly dance has always been also a form of public entertainment.

Travellers tribes, both in Egypt and Turkey, used to perform out in the streets.

Travellers are said to have come from India originally and then have migrated through modern Afghanistan and Iran to head some north, towards Turkey and Europe, and some south, towards northern Africa, including Egypt.

One way for travellers to earn a living was to perform to entertain people and they danced.

They probably brought with them their own dance traditions, but they must also have picked up the traditions and movement vocabulary of the places in which they travelled.

Turkey

The artists who travelled and performed in Turkey were called chengis.

We have record of them being active in Istanbul since the 1400s and they used to entertain particularly female audiences with dancing and singing.

They danced using intricate hip movements and torso articulations, shimmies, and they also used props, some of which we still use today, such as finger cymbals and veils.

Today chengis in Turkey still dance for tourists. Turkish dancing style has been heavily influenced by them.

Egypt

Performers in Egypt were not only women but also men (it was the European influence that later promoted female dancers at the expenses of men, as European travellers preferred to see women dance). The ethnic group that performed in public on the streets was called ghâwazî.

They used to dance in front of coffee houses and outdoors during public processions especially during saint’s day celebrations.

They would sing and dance and use various props, such as canes and swords. Public dance at first was not only tolerated by the authorities, but it was accepted as part of the tradition and also because performers were taxed and, therefore, brought in revenue.

However, in 1834, the political situation changed and the authorities gave into pressure from the most conservative fringes of society and outlawed public dancing in Cairo.

Hence, many performers continued dancing outside of Cairo, but the potential for making a good living outside the capital was slimmer.

Between 1849 and 1856, however, the ban was lifted so performers returned to Cairo.

The beginning of the XX century, around the 1920’s, saw the opening and flourishing of various nightclubs where dance was performed and were the audience was made up mainly by Europeans.

Hence, the dancing style changed because of the need to please a foreign audience and modern raqs sharqi was born.

One of the most famous nightclubs of this type was the one that belonged to Badiia Masabni in Cairo in the 1920s.

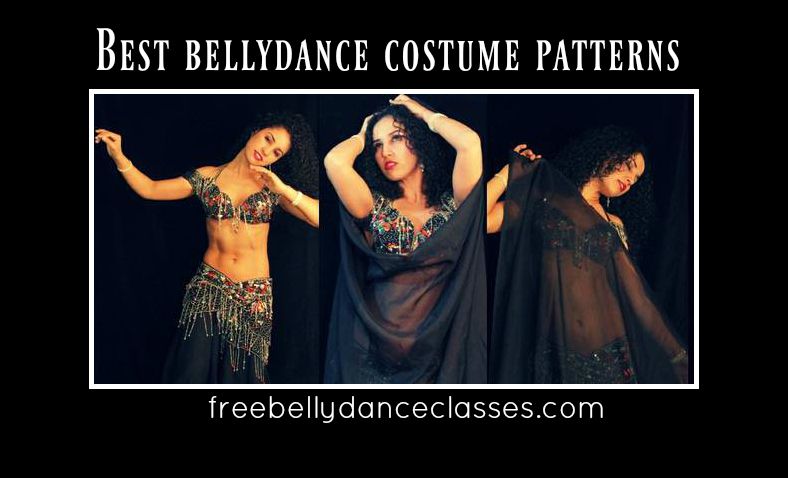

In this setting, dance was adapted to the stage, set choreographies and group performances were introduced and also there was a big influence from western types of dance, such as ballroom dancing and ballet. The costumes changed as well.

Up until that point dancers wore a wide long skirt, a shirt and a waistcoat.

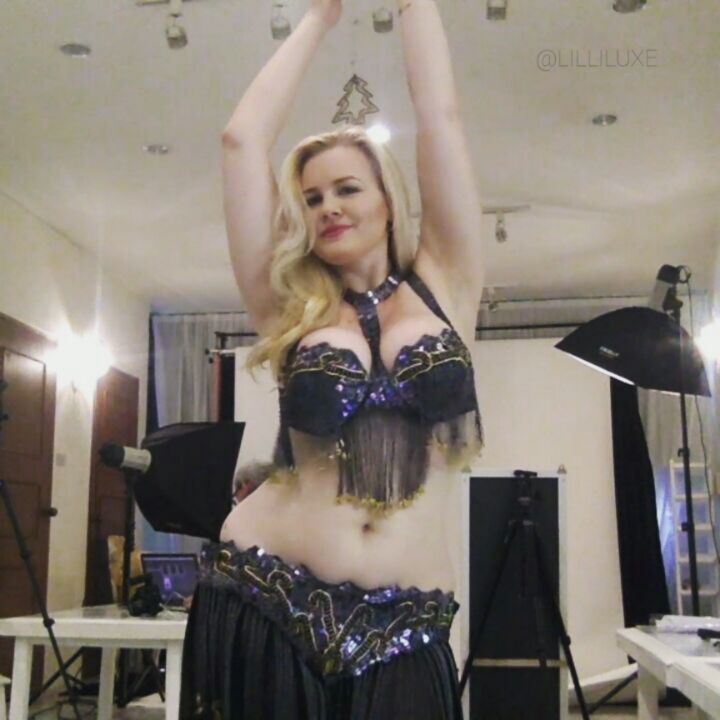

From the 1920s dancers started wearing what is known today as the typical belly dancer’s costume (bedlah): a bra, a skirt, bare midriff, veils, a lot of glitter and beads.

Western Society

Middle Eastern dance spread into Europe and the USA at first because of European travellers who went to the Middle East and northern Africa from the late 1700s and through the 1800s.

Reactions from the part of these travelers were mixed. Some hated this dance, some loved it.

Some hated this dance, some loved it.

However, as the majority of these travelers were male, they did not have access to all types of performers, as some would only perform for women-only audiences.

They were only able to see performers on the street or those women dancers who were willing to perform privately in front of a male-only audience.

Hence the reason why dancers had a bad reputation among foreign visitors.

With the universal exhibitions, curiosities from all over the world were brought into Europe and the USA.

In particular, the 1893 Chicago World Fair was especially significant for the spread of belly dance in the west.

A dancer called Little Egypt performed there and she started a wave of controversy.

Some loved her movements but others were scandalised by them (think of what effect must have had a dance in which the torso moved freely, in a society where women wore corsets).

Many imitated her movements, but exaggerating the hips and torso movements in a way that many considered vulgar.

Also, western people had an imaginary picture of the orient in their minds, as a land of passion and moral ambiguity. Hence, oriental women and dance were seen in the same light.

This distorted image of the orient became a subject of many popular books and was promoted even further by Hollywood movies.

Belly dance also influenced burlesque in the 1800s and this contributed to confusion in the mind of many between these two genres.

In recent years, thanks especially to the feminist movement in the 1970s and 1980s, more and more women (in the USA first, then all over the world, including Europe, Oceania and the Far East) have discovered the empowering nature of this dance form for women.

As for men, they still dance folkloric styles in the countries of origin of belly dance, but not Raqs sharqi. In the west, there are some male belly dancers but still very few and far in between at the moment.

You can also learn more about belly dance from sites such as IAMED (International Academy of Middle Eastern Dance).

References

- Shay, A. and B. Sellers-Young (2003). “Belly Dance: Orientalism: Exoticism: Self-Exoticism.” Dance Research Journal 35(1): 13-37.

- Nieuwkerk,K. (1995), A Trade like Any Other: Female Singers and Dancers in Egypt. University of Texas Press.

- Dinicu, C (2013), You Asked Aunt Rocky: Answers & Advice about Raqs Sharqi and Raqs Shaabi. Rdi Publications.

- Lo Iacono (2019) – Dance as Living Cultural Heritage: A Transcultural Ethnochoreological Analysis of Egyptian Raqs Sharqi.

Unpacking the Cultural Baggage & History of “Belly Dance”

“Belly dance” is a colonial misnomer placed on dances from the Middle East, North Africa, Turkey and Greece. It stereotypes and pigeonholes a rich and complex art form and erases the people and cultures it comes from. Why are we still using the term? Let’s unpack a bit of the history and cultural baggage behind it.

Over the past few years and especially the past couple of months, I have been doing a lot of deep reflection on the art form I have dedicated the latter half of my life to, the dance most people where I'm from know as "belly dance. "

"

I have been reflecting deeply on the terminology I use, how to define this dance and how to describe what I do to people who don't know me, to paint a more accurate picture of my life's work. I have also been reflecting on my role as a non-Arab woman, living in the US and teaching an Arab dance.

The truth is that average people in our culture don't actually know what belly dance is, and upon hearing this term the image they conjure up in their heads is, at worst, a wildly inaccurate representation of what I do, and at best it is a simplistic and incomplete view of an extremely rich, culturally diverse and socially complex art form that is both incredibly beautiful and powerfully transformative.

The picture of me, sexily shaking my bits in a sparkly 2-piece costume does not even begin to account for everything this dance is, everything it represents, and everything that is involved when someone decides to seriously learn belly dance. The costume and the movement are only a tiny fraction of what this dance actually is or could be.

"Belly dance" is a broad umbrella term for Middle Eastern, North African, Hellenic & Turkic (MENAHT) dances that involve articulated movements of the hips and torso. But belly dance is also a misnomer given by colonialist men, to dances that were native to countries they were colonizing, dances that in many cases were primarily done by women. Do you see what’s wrong with this picture?

The term caught on, and these days it also encompasses the versions of these dances which have evolved in non-native countries all over the world, including fusion forms that bear less resemblance to the original dances that still live on and continue to evolve in MENAHT countries today.

Because it’s such a convenient, broad term that encompasses such a variety of dances, it has been difficult to come up with any term to replace it. It’s also the only term that the general public knows them by, so it’s how new people interested in learning these dances are able to find their teachers. But it is also simultaneously a term that pigeonholes us into stereotypes and limiting roles, and it can also discourage people from learning this dance altogether.

But it is also simultaneously a term that pigeonholes us into stereotypes and limiting roles, and it can also discourage people from learning this dance altogether.

Why is that? First of all, “belly dance” is a term that zooms in on one specific body part. It leads some people to think that all it takes is to shake or undulate this body part, and thereby dismiss it as a silly activity that doesn’t warrant any serious study or dedication. At the same time, others might think they could never do it because their bodies just don’t move that way (spoiler alert: anyone’s body could move that way with enough practice and good teaching).

Additionally, I would estimate that there are millions of women in our country who would give this dance a try if its name didn’t immediately confront them with a part of their body that is tied with their self-esteem in a negative way. In our culture, we are taught that “fat = BAD” and that we must have a toned belly to be deemed beautiful and worthy. This is a lie that many women are finally beginning to unpack and unlearn, but still for most women the idea of putting so much focus on a physical part of ourselves that we dislike can be extremely intimidating and off-putting.

This is a lie that many women are finally beginning to unpack and unlearn, but still for most women the idea of putting so much focus on a physical part of ourselves that we dislike can be extremely intimidating and off-putting.

Yet the reality is that people of any body type can belly dance. It’s a dance that looks beautiful on any body, without weight, age, or gender restrictions. And it’s a dance that involves so much more than just belly, hips and chest movements. It also involves footwork, arm movements, feeling and expression, understanding various different genres of MENAHT music, instruments and rhythms, familiarity with classic Arabic songs, connecting with the lyrics in their original language/s, and knowing the basics of different folkloric dances from various regions of the Middle East.

When we use the misnomer “belly dance,” we are omitting these important aspects of the art form and contributing towards the erasure of the rich and diverse cultures and people that it comes from. MENAHT people and their cultures are not well represented in here in the United States. They are stereotyped and misunderstood at best, profiled and oppressed at worst. To practice, perform and teach a dance that comes from their countries without acknowledging their cultural context contributes to the stereotyping and oppression so many still suffer from.

MENAHT people and their cultures are not well represented in here in the United States. They are stereotyped and misunderstood at best, profiled and oppressed at worst. To practice, perform and teach a dance that comes from their countries without acknowledging their cultural context contributes to the stereotyping and oppression so many still suffer from.

So, what do we call it instead? Years into my personal reflections on this subject, I still have not arrived at a concrete answer. I am becoming comfortable with the idea that this is an evolving discussion and that my thoughts and approach towards this subject will continue to evolve and change over the years. I am comfortable with the fact that people’s opinions on this subject will differ and many disagree with my approach. I respect those differing opinions, and accept that everyone is arriving at their own answers in their own time. What’s most important is that we continue to learn and be open to having these conversations, and especially to hearing the opinions and experiences of dancers from source countries!

While I still continue to use “belly dance” as a broad term, for lack of a better broad term, for simplicity’s sake and to help new students and clients find me, more and more I refer to what I perform and teach as “raqs sharqi” among my existing students and even to people outside of the belly dance industry/community. Calling it “belly dance” encourages assumptions and stereotypes they already held. “Raqs sharqi” piques their curiosity and invites discussion (with that said, when I am dancing fusion, or dancing to non-Arabic music, I revert back to the broad term “belly dance”).

Calling it “belly dance” encourages assumptions and stereotypes they already held. “Raqs sharqi” piques their curiosity and invites discussion (with that said, when I am dancing fusion, or dancing to non-Arabic music, I revert back to the broad term “belly dance”).

Raqs sharqi is Arabic for “Eastern dance” or “Oriental dance.” It’s what Egyptians call the stage version of the dance we know as “belly dance.” Since I primarily focus on learning from Egyptian style teachers, that can be a fitting term for me to use. But the term will depend on the language, so for a Turkish style dancer, perhaps “Oryantal dans” (the Turkish language equivalent of the term) could be more fitting. What’s important to note is that nowhere in MENAHT countries are any of the dances we call “belly dance” referred to by a body part like it is here, but since my studies focus on Egyptian style, I will be using Egyptian (Arabic) terminology on this post, and please be aware that my knowledge of the history of this dance is very much Egypt-centric.

Raqs sharqi is a stage adaptation of various dances mixed together, including raqs baladi ("country dance"), one of the social dances done in Egypt which uses hip and chest "isolations", shimmies and basic steps and is very casual and relaxed ("belly dance" in its most raw, unpolished, original form). This type of social dance is not exclusive to Egypt, it's done in most if not all Arab countries (alongside other social dances), it’s done by women and men in many cases, but in some regions it may be done primarily by women. It is simply the way people dance amongst each other when they get together for a party, wedding or other celebration.

The specific music used, the stylization of the movements and the name used to refer to this type of dancing will vary by country/region. There are non-Arab countries in the Middle East/Mediterranean that dance socially like that, in their own ways, like Israel, Turkey (where it's called çifteteli) and Greece (tsifteteli).

In Egypt, the stage adaptation we call "raqs sharqi" ("oriental dance") came about in the late 1800’s and incorporated elements of raqs baladi (“country dance”) with the performative styles that were done by the ghawazee and awalim who were professional dancers/entertainers who performed at weddings and other celebrations at the time.

It also incorporated some elements of non-MENAHT dances like ballet and ballroom and other forms that the earliest raqs sharqi dancers happened to have trained in (Latin dances, acrobatics, and more). The evolution of this dance is very interesting as all the most famous dancers had such a unique and different style and each became highly influential in shaping the development of the dance. Much of the evolution of raqs sharqi happened around the time of the Golden Era of Egyptian cinema, and people all over the Arabic-speaking world were watching Egyptian movies which often featured dancing scenes by famous raqs sharqi dancers, who were actresses too!

Lastly, raqs sharqi also incorporates bits of various different Arab folk dances when the music calls for it… it’s a lot to learn!

Here in the US, this very rich and complex dance was reduced to just a titillating dance for many reasons. Colonialism, orientalism, patriarchy to name a few. When “belly dance” was originally introduced to the “Western” world in the late 1800s, it was not raqs sharqi but social and folkloric dances from colonized countries (in North Africa and the Middle East), done by women who were brought over from those countries by colonizer men (French, British, Americans), taken completely out of their native context, and presented in a sensationalized way to make money for those men. This was happening during a time when Western women wore corsets and showing your ankles as a woman was considered scandalous. So even though those dancers brought over originally were fully covered when performing, the fact that they moved their hips freely was considered extremely vulgar and scandalous and it attracted viewers due to the shock factor. And so the infamous reputation of “belly dance” began and we have never been able to fully overcome those associations.

The real evolution and growth in popularity of “belly dance” in the United States didn’t really start until around the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s though, as immigrant dancers from different countries in the Middle East (Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, etc) began to set up classes here and taught Americans how to perform.

The style that evolved here was called “American cabaret,” it evolved differently in different regions of the US and was a mix of various Middle Eastern styles of belly dance, since this country is such a melting pot of different cultures. In the 70’s, Middle Eastern clubs were booming, featuring long belly dance shows with live music, and the bands here were made up of musicians from all over the Middle East, so American dancers at the time had to know how to dance to Arabic, Turkish, and Greek music. But without the social/cultural context, and with the revealing costumes worn, what Americans saw was still a scandalous dance. And in the eyes of the patriarchy, there is no reason a woman would want to move her body like that other than to please or seduce a man.

In the 70’s, Middle Eastern clubs were booming, featuring long belly dance shows with live music, and the bands here were made up of musicians from all over the Middle East, so American dancers at the time had to know how to dance to Arabic, Turkish, and Greek music. But without the social/cultural context, and with the revealing costumes worn, what Americans saw was still a scandalous dance. And in the eyes of the patriarchy, there is no reason a woman would want to move her body like that other than to please or seduce a man.

This, coupled with ignorant but prevalent Orientalist stereotypes of Arabs and Middle Easterners in general meant that the image of the “sultan’s harem” and the idea of “seducing the sultan” became intricately connected with the image of the “belly dancer” here in the US. Of course, since sex sells, this is something that many club owners and belly dancers themselves used to their advantage. This helped to cement the reputation of “belly dance” as something purely sexual and scandalous here in the US, which unfortunately led to it being reduced, dismissed, and ridiculed by the general public, something that continues to this day.

Here it’s important to add that performing belly dance/raqs sharqi in public is also very taboo in most MENAHT countries. In some countries it is forbidden, in others it is forbidden for natives but allowed for foreigners, and in others it is allowed but you are ostracized for being a belly dancer. In Egypt for example, belly dance (raqs baladi & raqs sharqi) is a huge part of their culture, it’s done socially at every gathering and at any major celebration a belly dancer is hired to perform and is often the main attraction. They love and appreciate the dance, and they generally dance the social form of it at parties and other gatherings (where it happens in gender-segregated settings for the more religiously conservative/modest, and in mix-gender settings for the less conservative), but a woman who is paid to dance is not seen as respectable.

So belly dance being considered “provocative” isn’t necessarily unique to our culture. It’s just that in the cultures of origin, there are layers of appreciation and admiration amid the layers of taboo and condemnation. In the countries of origin, it is done socially for fun and celebration and not just viewed as a dance of seduction and provocation.

In the countries of origin, it is done socially for fun and celebration and not just viewed as a dance of seduction and provocation.

To really do this dance justice we have to get comfortable with this dichotomy instead of pigeonholing ourselves into a single stereotype. To do so as non-MENAHT outsiders means opening up a door into cultures and customs we may not otherwise have been exposed to. We have to learn movements that are difficult for us because we haven’t been doing them socially with our family and friends our whole lives, but which are so beneficial and rewarding for countless reasons… but this dance is so much more than just movement.

Music, culture, and language are all intricately connected with the movements of this dance. It is a lifelong study, which far from just working your belly, will work your entire body, your brain, and your heart while deepening your connection to the rest of humanity.

Was this post helpful? Would you like to learn more about belly dance/raqs sharqi? Hit "like" below, share, and leave a comment with your feedback!

You can also visit our blog map to find more posts like this, or subscribe to our newsletter or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post.

If you'd like to learn belly dance online with us, check out our available classes here.

Belly dance: history

Dance Center "Visit" > Belly dance school > Articles > "Belly dance: history"

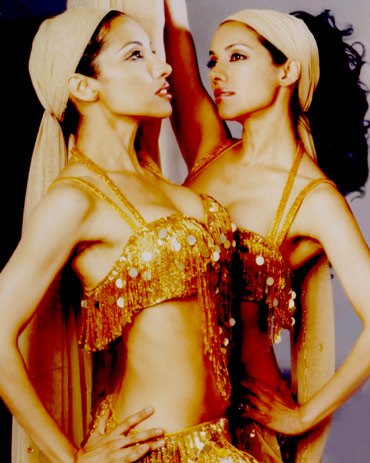

The mystery of bellydance is not only in the eyes of the dancer, charming atmosphere and magical attraction, but also in its history.

No one can say exactly where belly dance originated and when it happened. Most researchers are inclined to believe that the birthplace of bellydance is in Egypt, someone believes that it is in Mesopotamia, or maybe its origins should be sought in India? In ancient Greek manuscripts, one can find descriptions of Nile dancers who used various types of shaking and vibrations in their movements. The frescoes of the ancient temples of Egypt and Mesopotamia, painted a thousand years BC, depict priestesses performing this bizarre dance - a sacred ritual dance dedicated to the goddess of fertility, the mother goddess. The peoples of different countries - and already in ancient times, a characteristic oriental dance was performed in North Africa, and in Greece, and in Rome, and in Babylon - called it differently: Anahita, Isis, Ishtar, Aphrodite. The "dance guides" between these countries were the gypsies. But not modern, familiar to us, "Roma", but "Sinti" - another linguistic group. In Egypt, they were called "ghawazi" - "foreigners", and they came to the Nile Valley from India. Traveling from region to region, they brought with them the culture of belly dance, supplementing it in each country with new movements. By the way, later in Spain - again with the light hand of the gypsies - this intercultural mix became the basis of flamenco, only the emphasis from the stomach and hips shifted to the legs and arms.

The peoples of different countries - and already in ancient times, a characteristic oriental dance was performed in North Africa, and in Greece, and in Rome, and in Babylon - called it differently: Anahita, Isis, Ishtar, Aphrodite. The "dance guides" between these countries were the gypsies. But not modern, familiar to us, "Roma", but "Sinti" - another linguistic group. In Egypt, they were called "ghawazi" - "foreigners", and they came to the Nile Valley from India. Traveling from region to region, they brought with them the culture of belly dance, supplementing it in each country with new movements. By the way, later in Spain - again with the light hand of the gypsies - this intercultural mix became the basis of flamenco, only the emphasis from the stomach and hips shifted to the legs and arms.

But back to the East. Over time, the “religious matriarchy” was replaced by patriarchal religions, paganism was replaced by Christianity and Islam, and belly dancing turned from a ritual act into secular entertainment. A number of researchers even reduce bellydance to the level of “harem fitness” - they say that the wives and concubines in the harem had nothing to do, and it was necessary to monitor the beauty of the body, so they were engaged in belly dancing to while away the day with a fun activity and keep the body in shape . But even in the harem, belly dance had an important sacred task - to prepare a woman for pregnancy and childbirth. The specific movements of the dance involve the internal muscles of the pelvis - the very ones that help the baby to exit the uterus - and thanks to this, childbirth is easier and painless. The role of bellydance is not limited to pure physiology - for example, in some Egyptian villages, women still gather in a large tent and dance around a woman in labor, on the one hand, to help her morally, and on the other, to meet the newborn with fun so that he lives a happy life.

A number of researchers even reduce bellydance to the level of “harem fitness” - they say that the wives and concubines in the harem had nothing to do, and it was necessary to monitor the beauty of the body, so they were engaged in belly dancing to while away the day with a fun activity and keep the body in shape . But even in the harem, belly dance had an important sacred task - to prepare a woman for pregnancy and childbirth. The specific movements of the dance involve the internal muscles of the pelvis - the very ones that help the baby to exit the uterus - and thanks to this, childbirth is easier and painless. The role of bellydance is not limited to pure physiology - for example, in some Egyptian villages, women still gather in a large tent and dance around a woman in labor, on the one hand, to help her morally, and on the other, to meet the newborn with fun so that he lives a happy life.

The "harem period" of the history of belly dance is the most controversial and vague. The fact is that Islam forbids depicting people, forbids women to dance for someone other than other women or their husband, and for strangers to enter the female half of the house (“haram” in Arabic means “forbidden”). Therefore, there are neither drawings of that time depicting dancers, nor descriptions of their movements. The few things that give us an idea of what happened outside the walls of the harem are either the memories of the wives of European diplomats, or the figment of the imagination of artists and writers who often did not even visit the East. Should they be trusted?

The fact is that Islam forbids depicting people, forbids women to dance for someone other than other women or their husband, and for strangers to enter the female half of the house (“haram” in Arabic means “forbidden”). Therefore, there are neither drawings of that time depicting dancers, nor descriptions of their movements. The few things that give us an idea of what happened outside the walls of the harem are either the memories of the wives of European diplomats, or the figment of the imagination of artists and writers who often did not even visit the East. Should they be trusted?

And in the Egyptian chronicles, mention of the Ghawazi can only be found in the last two hundred years. This people did not strictly adhere to the canons of Islam, they danced in the streets with their heads uncovered - naturally, such behavior caused displeasure of religious leaders, and it was forbidden to write about the Ghazi. The very first drawings on which you can see the costumes of that time - narrow fitted caftans and wide trousers - were made by European travelers in the middle of the nineteenth century. These costumes strongly resembled Turkish folk clothes - which is not surprising, because Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 to 1805 - and Turkish costume, in turn, borrowed a lot from Persian. With their “immoral” behavior, the Ghazi, who danced for money for the soldiers of the Turkish army, incurred the wrath of not only the faithful Arabs, but also the Turkish Pasha - and were exiled to the south of Egypt in Esna.

These costumes strongly resembled Turkish folk clothes - which is not surprising, because Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 to 1805 - and Turkish costume, in turn, borrowed a lot from Persian. With their “immoral” behavior, the Ghazi, who danced for money for the soldiers of the Turkish army, incurred the wrath of not only the faithful Arabs, but also the Turkish Pasha - and were exiled to the south of Egypt in Esna.

The second birth of bellydance took place in the middle of the nineteenth century - an unprecedented interest in it flared up in Europe after the conquest of northern Africa by the French. All sorts of oriental shows became popular - however, it must be admitted, often it was only a cheap imitation without the slightest hint of culture and the deep meaning of belly dance. The first show with real oriental dancers was shown in Paris in 1889, and in 1893 the American impresario Saul Bloom brought a troupe of folk dancers from North Africa to the World's Fair in Chicago and coined the flamboyant term "bellydance", literally - "belly dance" . In the same year, Oscar Wilde's play Salome was banned in London for its "lewd dancing" - which only spurred interest in them.

In the same year, Oscar Wilde's play Salome was banned in London for its "lewd dancing" - which only spurred interest in them.

But then, compared to both ancient times and today, everything looked rather chaste – the dancers performed in long, closed dresses, and only a tied scarf accentuated the hips. However, this was enough: the fatal female spy Mata Hari literally enslaved the hearts and will of the powerful with her oriental dances. Bellydance was inspired by Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Martha Graham.

Hollywood gave bellydance its current glamor. It was in Hollywood films that dancers first appeared with an open stomach, in an embroidered bodice and with a belt at the waist. Egyptian dancers partially copied this image, lowering the belt from the waist to the hips, exposing the navel - this way the movements looked more impressive, and it was easier to see them. Cinematography also laid the foundations for the choreography in bellydance - before the dance from beginning to end was pure improvisation, and in group performances captured on film, it looked somewhat inconsistent.

In Egypt, cinematography flourished in the forties of the last century, and directors, of course, sought to make films with famous dancers. These films generated a genuine interest in bellydance far beyond the Middle East. Women and even men of Western countries wanted not only to watch colorful shows, but also to dance this bewitching mysterious dance themselves. This interest has not subsided until now.

Victoria Pyatygina

Belly dance at 79years: in Rostov-on-Don, a pensioner wins in beauty contests

Komsomolskaya Pravda

SocietyPICTURE OF THE DAY

Olga GOPALO

December 4, 2017 17:59

Now a lady is begging to write her down in a circle medals [video]

A woman has always dreamed of dancing. Photo: courtesy of "Image Center"

Who said that at the age of 79 the only thing left to do is pass the time on the benches at the entrance or in clinics at the doctor's office? Pensioner Karina Didenko does not think so. A few years ago, a former chemistry and biology teacher begged to enroll her in an Arabic dance class. And on December 3, she received her 13th gold medal for her performance at the International Dance Forum "Eurasia", where representatives of eight cities of the Southern Federal District participated.

A few years ago, a former chemistry and biology teacher begged to enroll her in an Arabic dance class. And on December 3, she received her 13th gold medal for her performance at the International Dance Forum "Eurasia", where representatives of eight cities of the Southern Federal District participated.

A few years ago, my grandmother begged her to enroll her in a dance club. Photo: courtesy of "Image Center"

"LIFE JUST BEGINS!"

- A few years ago we announced the "Grand Lady Charm" contest, - told the head of the Image Elite modeling school Elena Stepura . - A competition that would enable women, regardless of their external data, physique and age, to express themselves on stage. When Karina (a woman does not allow herself to be called by her patronymic - author's note) went on stage and performed a belly dance, we were simply shocked. Say what you like, but for some, by the age of 80, life is just beginning!

Now Karina Didenko from Rostov is a welcome guest at many city events. In her dance steps, she easily gives odds to the young. And every performance is accompanied by thunderous applause.

In her dance steps, she easily gives odds to the young. And every performance is accompanied by thunderous applause.

- I always dreamed of dancing, - Karina Didenko confesses to the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper - Rostov. - I've been dancing all my life: anything - just to dance. After the war, I was in the orphanage for ten years: my mother is an enemy of the people, my father did not come from the front. So I ended up in a government institution on Sakhalin. Since the town was small, visiting artists had nowhere to stay, and they stayed with us. Due to the time difference, many could not fall asleep, and therefore often worked with us, instilling their creativity. They gave us great lessons. I know ballet and all ballroom dancing - Hungarian, Spanish and so on.

Now the dancer is getting gold medals in dance competitions. Photo: provided by "Image Center"

"I WAS AFRAID - BECAUSE OF AGE THEY WILL NOT TAKE IT"

True, Karina liked oriental dances the most.

- This was already in the time of Khrushchev. When in 1954 he brought the film "Tramp" to the Union, I simply fell ill with oriental dances, - she recalls. - But because of the heavy workload (all my life I taught children chemistry and biology, and in recent years I was a primary school teacher) I danced only at home in front of a mirror. And in the USSR, these dances were banned. I suffered greatly from this. And then she retired, saw an ad in the newspaper about recruiting into an oriental dance group. Arrived on the appointed day and time. I was very afraid that they would not take me because of my age. And because I started chattering, I talk and talk, but I myself am afraid that I will stop and they will say “no” to me. I asked for at least a month. She promised to listen and not miss.

Now the pensioner goes to classes twice a week. And she also takes individual lessons when they put on a dance just for her.

Most of all Karina liked oriental dances. Photo: courtesy of the "Image Center"

Photo: courtesy of the "Image Center"

"YEARS, OF COURSE, SOMETIMES SHOULD BE KNOWN"

- The biggest difficulty was deciding what to call me as a teacher: she's good enough for my granddaughter, - continues the interlocutor . - But I immediately said: no patronymics. After a few lessons, she began to praise me: “Good, Karinochka!” This is so nice. True, age, of course, sometimes makes itself felt. And until now, maybe not everything is possible the first time: for example, to bend, like the young. But I'm trying. And I suggest a lot to them: when she expresses herself in terms, they do not understand everything. I say: put the leg inside out, and it will be as the teacher wants. Now I'm finally free. And I know the canons: how to put the brush correctly, where to put the elbow. It became beautiful and danceable. And they let me out on stage, because plasticity and harmony are combined in my dance, it turns out beautifully.

Moreover, the pensioner is not going to stop there.

- I don't know how long I will dance, - says the woman . - I know one thing for sure: I will dance all my life. And maybe someday I'll be carried off the stage. After all, dance is my whole life. I can't imagine it without him now.

Belly dance at 79

SEE ALSO

In the Rostov Region, a 65-year-old pensioner from the city of Salsk can immediately pull a driver and a GAZelle weighing more than two tons. And this is with a height of 164 centimeters and a weight of 71 kilograms. The other day, she demonstrated her power extreme skills right on one of the city streets. The grandmother of four grandchildren, the owner of shops, a sewing workshop for tailoring ritual accessories and even her own atelier, is sure that life is just beginning after retirement.(Details)

0049

From a sysadmin to a bodybuilder: at 60, a Rostovite looks like Schwarzenegger

How to become a hand-written handsome man at 60 and get first places in beauty contests? This is not a rhetorical question.