How does dance therapy work

FAQ

General Questions

What is dance/movement therapy?

The American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA) defines dance/movement therapy as the psychotherapeutic use of movement to promote emotional, social, cognitive and physical integration of the individual.

Dance/movement therapy is:

- Focused on movement behavior as it emerges in the therapeutic relationship. Expressive, communicative, and adaptive behaviors are all considered for group and individual treatment. Body movement, as the core component of dance, simultaneously provides the means of assessment and the mode of intervention for dance/movement therapy.

- Practiced in mental health, rehabilitation, medical, educational and forensic settings, and in nursing homes, day care centers, disease prevention, health promotion programs and in private practice.

- Effective for individuals with developmental, medical, social, physical and psychological impairments.

- Used with people of all ages, races and ethnic backgrounds in individual, couples, family and group therapy formats.

What do dance/movement therapists do?

Dance/movement therapists focus on helping their clients improve self-esteem and body image, develop effective communication skills and relationships, expand their movement vocabulary, gain insight into patterns of behavior, as well as create new options for coping with problems. Movement is the primary medium dance/movement therapists’ use for observation, assessment, research, therapeutic interaction and interventions. Dance/movement therapists help develop treatment plans and goals, document their work in clinical records and collaborate with professionals from other disciplines.

Where do dance/movement therapists work?

Dance/movement therapists work in a variety of settings including nursing homes, schools, psychiatric, rehabilitation and medical facilities, drug treatment centers, counseling and crisis centers, and wellness and alternative health care centers.

What does a dance/movement therapy session look like?

The extensive range of dance/movement therapy techniques and the needs and abilities of participants allow for a wide variety of movement activities in dance/movement therapy sessions. Dance/movement characteristics, from subtle and ordinary movement behaviors to expressive, improvisational dancing could occur.

To learn more about the ways in which dance/movement therapists work, go to the ADTA YouTube page and Profiles of DMTs.

How can I become a dance/movement therapist?

There are two routes one can pursue to become a dance/movement therapist. View the R-DMT Applicant Handbook for an in-depth guide of requirements.

#1: ADTA Approved Graduate Program

Graduates of approved programs meet all professional requirements for the Registered Dance/Movement Therapist (R-DMT) credential. Please contact the school directly for application process, requirements, etc.

Please contact the school directly for application process, requirements, etc.

#2: Alternate Route

The Alternate Route is defined as a Master’s degree with dance/movement therapy training from qualified teachers. Other requirements include movement observation and assessment, psychology coursework, fieldwork, internship, and dance experience.

What degree/credential do dance/movement therapists receive?

The dance/movement therapy credential is awarded at the graduate level. Therefore, a Master’s degree is required. Upon completion of an ADTA Approved Graduate Program or the Alternate Route and acceptance by the Dance/Movement Therapy Certification Board, the Registered Dance/Movement Therapist (R-DMT) credential is awarded. R-DMT represents attainment of a basic level of competence, signifying both the first level of entry into the profession and the individual’s preparedness for employment as a dance/movement therapist within a clinical and/or educational setting. The Board Certified Dance/Movement Therapist (BC-DMT) credential can be obtained after the R-DMT is awarded, with additional requirements and experience. BC-DMT is the advanced level of dance/movement therapy practice, signifying both the second level of competence for the profession and the individual’s preparedness to provide training and supervision in dance/movement therapy, as well as engage in private practice.

The Board Certified Dance/Movement Therapist (BC-DMT) credential can be obtained after the R-DMT is awarded, with additional requirements and experience. BC-DMT is the advanced level of dance/movement therapy practice, signifying both the second level of competence for the profession and the individual’s preparedness to provide training and supervision in dance/movement therapy, as well as engage in private practice.

What undergraduate degree should I pursue?

At the undergraduate level, there is no specific degree required. However, it is a good idea to have substantial exposure to topics related to both dance and psychology. For specific prerequisites, contact each ADTA Approved Graduate Program.

Where can I find information on how to volunteer/shadow a dance/movement therapist?

Opportunities to volunteer/shadow a dance/movement therapist are limited due to the nature of the work and the need for confidentiality. If you are interested in volunteering/shadowing, contact your region’s Member-at-Large or a local chapter.

What kinds of experience would be helpful for a future dance/movement therapist?

It is strongly encouraged to pursue a broad practice in dance, including a variety of dance styles and techniques, choreography, performance, and teaching. For education, focus on psychology courses and a course in kinesiology and anatomy. Helpful experience would include working or volunteering with people in various human service settings (i.e. summer camps, schools, hospitals, nursing homes).

How long does it take to become a dance/movement therapist?

If attending an ADTA Approved Graduate Program, expect to be in school for two to three years, full-time. For the Alternate Route, the length of time depends on many factors, such as committing full or part-time, location of courses (some travel may be required), when courses are offered, when the individual can attend, etc.

What school would you recommend?

Attending any of the ADTA Approved Graduate Programs provides in-depth knowledge and training from exceptional, experienced, board certified dance/movement therapists. The ADTA suggests contacting and/or visiting the school(s) to help decide if the institution is a good fit.

The ADTA suggests contacting and/or visiting the school(s) to help decide if the institution is a good fit.

What does approval of graduate programs mean?

The ADTA approves programs that meet the requirements stated in the ADTA Standards of Education and Clinical Training. Graduates of approved programs meet all educational requirements for the Registered Dance/Movement Therapist (R-DMT) credential.

Where can I find a list of Alternate Route offerings in my area?

Ongoing Alternate Route course offerings can be found in the Alternate Route Course Calendar and in the Alternate Route Graduate Coursework documents contained on the Alternate Route page. Also, check the Announcements section under the Forum, ADTA on Facebook, and ADTA LinkedIn.

Where can I find information on licensure requirements?

Licensure requirements vary state by state. Contact your state licensing board directly. Find your state’s board on the State Professional Counselor Licensure Board List.

Benefits, how it works, and more

Dance movement therapy is a psychotherapeutic tool that may improve wellness. Proponents recommend this intervention on the basis that the body and mind interconnect, meaning that anything that affects the body will also affect the mind.

The existing research is still in the preliminary stages, but a few studies suggest that this therapy may offer several benefits, such as reducing depression, improving gait in Parkinson’s disease, and lowering high blood pressure. Further studies are necessary to verify these benefits, though.

Keep reading to learn about how dance movement therapy works and the potential benefits.

According to the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA), dance movement therapy, also known as dance therapy, is the psychotherapeutic use of movement to improve health and well-being.

The intervention is a holistic approach to healing that emerged in the 1940s. Many of the early innovators of the field were accomplished dancers who began to realize that movement was a form of psychotherapy.

The ADTA explains that dance therapy promotes health through coordinating and unifying all aspects of a person, including:

- physical

- mental

- emotional

- social

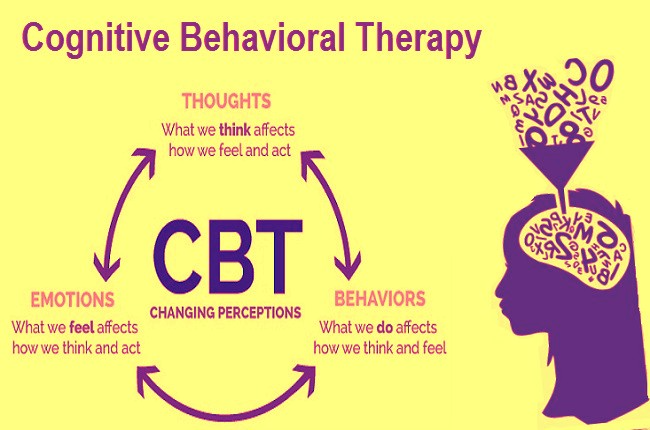

A premise that underlies the intervention is the belief that it is impossible to separate the body from the mind. As a result, changes in the body affect the mind and vice versa. The ADTA adds that the below premises also play a role:

- Dance is a means of nonverbal communication. Nonverbal language is as important as verbal language.

- In addition to serving as a means of communication, movement can be expressive, functional, and developmental.

- Movement serves as a tool for both assessment and intervention.

The research on the physical, mental, and emotional benefits of dance therapy has some inconsistencies. Although more studies are necessary to provide proof, some evidence suggests that the intervention may have value for the following:

Psychological health

Researchers looking to determine the benefits of dance therapy for a variety of psychological aspects of health carried out a 2019 meta-analysis that looked at 41 clinical trials and involved a total of 2,374 participants. The results suggested that the intervention improves:

The results suggested that the intervention improves:

- anxiety

- depression

- quality of life

- cognition, meaning the ability to think and remember

- interpersonal skills

They also indicated that these benefits might be long-term.

Depression

Whereas the above meta-analysis looked at psychological health quite broadly, a 2019 review dealt exclusively with depression. It evaluated eight clinical trials that explored the effects of dance therapy on 351 adults with the condition.

The authors characterized the evidence as being of moderate to high quality and concluded that the intervention might offer an effective treatment for adults with depression. However, they could not judge its effectiveness for children, teenagers, or older adults, as the included studies mostly excluded these populations.

Fall prevention

The authors of a 2017 review looked at whether dance, a popular pursuit among older adults, may help prevent falls by improving gait, balance, and muscle strength. Noting that falls are a leading cause of illness and death, the authors reviewed 10 clinical trials that explored a possible connection between dance and fall prevention. The trials had a total of 680 participants.

Noting that falls are a leading cause of illness and death, the authors reviewed 10 clinical trials that explored a possible connection between dance and fall prevention. The trials had a total of 680 participants.

Due to the preliminary nature of the results and the lack of long-term data, the authors were unable to draw firm conclusions. However, they note that dance appears to be safe and demonstrates well-being benefits in older adults.

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition that impairs gait, which can increase the risk of falls. A 2018 review looked at 40 studies and five reviews investigating the effects of dance and music on the symptoms of this condition. The results indicated that the interventions might improve gait.

Cancer care

The effects of cancer extend beyond physical health, as the condition often also influences emotions and socialization. In addressing such issues, current cancer care is increasingly including psychosocial interventions. To examine the benefits of dance therapy for cancer, a 2015 study reviewed three clinical trials that involved a total of 207 individuals with breast cancer.

To examine the benefits of dance therapy for cancer, a 2015 study reviewed three clinical trials that involved a total of 207 individuals with breast cancer.

The data analysis showed mixed results but indicated that the intervention might help by:

- improving vigor

- enhancing the quality of life

- reducing somatization, which is the presentation of multiple physical symptoms due to psychological causes

In contrast, it found no evidence that dance therapy can help with:

- tiredness

- stress

- anxiety

- depression

A 2021 review supports the finding that dance therapy can improve quality of life among people with breast cancer but notes that this therapy may be more effective alongside other treatments.

Blood pressure

A 2020 meta-analysis assessed five clinical trials that dealt with the effects of dance therapy on blood pressure. Despite the small number of trials, the results indicated that the intervention could significantly lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in people with hypertension.

Systolic pressure, the top blood pressure reading, denotes the pressure on the arterial walls during heartbeats. Diastolic pressure, the bottom blood pressure reading, denotes this pressure between heartbeats.

The results also suggested that dance therapy has more of an effect in people from Africa than those from Europe or America.

Chronic heart failure

An older 2014 study compared the effects of dance therapy with those of conventional therapy in individuals with chronic, or ongoing, heart failure. It evaluated two investigations that involved 62 dance therapy participants, 60 exercise participants, and 61 control participants.

When the researchers compared the effects of dance therapy with those of exercise and those of no exercise, they found that dance therapy increased exercise capacity and quality of life. There were no significant differences between the results of the dance therapy and conventional exercise groups. As a result, the authors recommend the inclusion of dance therapy in cardiac rehabilitation programs.

If a person wishes to get started, it is best to enroll in a program that a qualified dance therapist offers. Most of these professionals work in:

- rehabilitation centers

- psychiatric hospitals

- schools

- private practice

A therapist will customize the technique to suit an individual’s abilities and medical conditions. The movements can vary from ordinary and subtle to improvisational and expressive.

Some people may be interested in trying other creative therapies. These include:

- Art therapy: The American Art Therapy Association explains that this is the use of art-making to produce psychological benefits, such as:

- higher self-esteem

- improved cognition

- enhanced social skills

- Drama therapy: According to the North American Drama Therapy Association, this is the use of performance, purposeful improvisation, or story-telling to achieve therapeutic goals, such as better interpersonal relationships.

- Music therapy: The American Music Therapy Association notes that this is the use of music to render a variety of benefits, such as:

- physical rehabilitation

- managed stress

- increased memory

Learn more about other forms of creative therapy.

Dance therapy is a psychotherapeutic intervention that works by unifying and coordinating the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of a person.

Only limited research has explored the benefits, but early studies indicate that it might have value for some areas of wellness. These include psychological health, such as reducing symptoms of depression, and physical health, such as improving exercise capacity in people with heart failure.

Svetlana Ratnikova: how dance therapy works

Dancing appeared in my life, probably, as a realization of the need for movement. At the Faculty of Psychology, at some point, working with the word began to seem so painful to me that I wanted to quit everything. When I felt that there was nothing in my head but a pile of verbal constructions, I really wanted to just get up, forget about everything and dance. And it helped. Later, having become interested in dance therapy, I studied it at the Institute of Psychotherapy and Clinical Psychology and in the dance movement therapy programs of Alexander Girshon.

When I felt that there was nothing in my head but a pile of verbal constructions, I really wanted to just get up, forget about everything and dance. And it helped. Later, having become interested in dance therapy, I studied it at the Institute of Psychotherapy and Clinical Psychology and in the dance movement therapy programs of Alexander Girshon.

Dance Movement Therapy was developed by the American psychologist Merian Chase as a treatment for people who could not talk about their problems. It became widespread after the First World War. The specialist stood in front of the patient and began to move, and the patient gradually picked up the movement. Then the therapist watched the patient and repeated any of his movements in an enhanced version, as if working with a magnifying glass. The goal is to liberate the patient. In parallel, the therapist can ask questions. All this was supposed to lead to a surge of emotions in the patient, which were deeply hidden and could not find an outlet.

Later, dance therapy became widely used to expand and enrich the repertoire of dancers' movements. But the medical direction also remained in demand. Dance therapy is effective, for example, in working with autistic children who have difficulty making contact, especially verbal. If the child is small, you need to get down on the floor and move with him: dance or somersault - do whatever you like, trying to smoothly move into a dialogue.

Let me tell you how dance therapy works as an example. A girl came to me who had long wanted to start working with certain experiences, but could not make up her mind. For a long time she could not bring herself to even enter the room. I asked her what she would like to listen to, what kind of music she would be comfortable moving to now. She asked for "something sharp". I decided to try flamenco, and, listening to the music, it began to move sharply, twitching from side to side. I asked her what these movements could be connected with. She replied that she had seen something similar in her childhood, she associated these movements with her mother, petty quarrels with whom sometimes reached scandals and beatings. I concluded that the patient wanted to understand the mother's motivation, to find out what made her behave this way with her daughter. A few minutes later, the girl abruptly stopped moving and suddenly went limp, sat down and admitted that she could not relieve tension for a very long time, and now it worked out.

She replied that she had seen something similar in her childhood, she associated these movements with her mother, petty quarrels with whom sometimes reached scandals and beatings. I concluded that the patient wanted to understand the mother's motivation, to find out what made her behave this way with her daughter. A few minutes later, the girl abruptly stopped moving and suddenly went limp, sat down and admitted that she could not relieve tension for a very long time, and now it worked out.

The next time she came, she wanted to dance something light. It turned out that she can be very beautiful in motion, and I saw in her a person whom I had not known before, although we had known each other for a long time. This is a very joyful moment when a person changes, marvels at himself, discovers a new world for himself.

TDT: dance and movement therapy - Psychologos

Dance and movement therapy is one of the types of psychotherapy that uses movement as the basis for the development of a person's physical, social and spiritual life. Dance movement therapy is applicable to deal with many problems, some of which are emotional and interpersonal conflicts, fear of failure, lack of communication skills, low self-esteem. Also, this type of therapy is applicable to help people who have experienced a severe loss of a loved one, rape, severe mental illness, chronic illness. The psychotherapist with the help of dance helps people forget about problems, relax and assert themselves. The main advantage of dance-movement therapy in comparison with other types of therapy is that it is generally accessible, since when doing this type of therapy, the emphasis is not on the quality of the movements performed, but on the subtleties of a person's expression of his own emotions during movement, honest expression of feelings and absolute freedom of movement.

Dance movement therapy is applicable to deal with many problems, some of which are emotional and interpersonal conflicts, fear of failure, lack of communication skills, low self-esteem. Also, this type of therapy is applicable to help people who have experienced a severe loss of a loved one, rape, severe mental illness, chronic illness. The psychotherapist with the help of dance helps people forget about problems, relax and assert themselves. The main advantage of dance-movement therapy in comparison with other types of therapy is that it is generally accessible, since when doing this type of therapy, the emphasis is not on the quality of the movements performed, but on the subtleties of a person's expression of his own emotions during movement, honest expression of feelings and absolute freedom of movement.

During psychotherapist sessions, patients are often unable to talk about their problem to a specialist, as a result of which the session is not useful, since the psychotherapist does not identify the problem and, therefore, cannot offer the patient ways to solve it. If the psychotherapist during the session feels that the situation has reached a dead end and it is not possible to “talk” the patient in any way, he can ask the person to perform several movements to the music. Having traced the main tendencies in the movements of the patient, the psychotherapist with a high degree of probability can tell what his problem is.

If the psychotherapist during the session feels that the situation has reached a dead end and it is not possible to “talk” the patient in any way, he can ask the person to perform several movements to the music. Having traced the main tendencies in the movements of the patient, the psychotherapist with a high degree of probability can tell what his problem is.

A significant contribution to the development of dance-movement therapy was made by Wilhelm Reich's theory of the “muscle shell”. He proved for the first time that the tightness (“muscle shell”) of a person arises in childhood itself and is directly related to the fear of being punished, misunderstood, alienated, as well as the need for a person to constantly suppress his sexual sensations. As a result, complexes and clamps accumulate in the body and can lead to various mental and physical illnesses. Wilhelm Reich, who is the founder of body psychotherapy, believed that the patient's spontaneous body movements in combination with even, measured breathing can relieve muscle tension and effectively eliminate clamps and blocks that prevent a person from living.

According to one of the versions, the founder of dance-movement therapy as an independent type of psychotherapy is Gabriella Rott, a theater director, researcher of an innovative direction in theatrical art, a world-famous dance teacher, author of the famous “five rhythms” dance. Gabriella Rott's contribution to the development of dance movement therapy is invaluable - it was she who came up with special exercises that allow you to successfully solve most of the psychological problems of a person with the help of movement. The main idea of the exercises is to divide the human body into seven main zones:

- Zone number 1 - head and neck;

- Zone number 2 - shoulders;

- Zone number 3 - elbow joints;

- Zone number 4 - hands;

- Zone number 5 - pelvis and spine;

- Zone number 6 - knees;

- Zone number 7 - feet.

Now, based on this division of the body into specific zones, it is easy to determine the problem - if you feel constant tension and tightness in the head and neck, it means that the current speed of your thoughts and actions diverges from the optimal speed with which you are used to thinking and act. Perhaps the cause of the problem lies in the overly dynamic rhythm of your life or inefficient use of your own time with the subsequent forcing of life events. One way or another, you should stick to your usual pace of life. Feeling uncomfortable in zone number 2 indicates that you have taken on more obligations than you can handle. You should reconsider your life goals and priorities, perhaps you are not doing your true calling. If you feel tightness in your elbows (zone number 3), this indicates your indecision and excessive modesty, a clamp in zone 4 indicates your lack of self-confidence, a feeling of discomfort in the spine and pelvis (zone number 5) may indicate a certain degree of sexual complex. The way a person bends the leg at the patella (zone number 6) indicates a person's readiness for potential lifestyle changes. And finally, zone number 7 is an indicator of your ambitions, of what place in society you are striving to take. If your foot is completely in contact with the ground when walking, then you are determined to achieve all your life goals, your goals are objective and not contradictory.

Perhaps the cause of the problem lies in the overly dynamic rhythm of your life or inefficient use of your own time with the subsequent forcing of life events. One way or another, you should stick to your usual pace of life. Feeling uncomfortable in zone number 2 indicates that you have taken on more obligations than you can handle. You should reconsider your life goals and priorities, perhaps you are not doing your true calling. If you feel tightness in your elbows (zone number 3), this indicates your indecision and excessive modesty, a clamp in zone 4 indicates your lack of self-confidence, a feeling of discomfort in the spine and pelvis (zone number 5) may indicate a certain degree of sexual complex. The way a person bends the leg at the patella (zone number 6) indicates a person's readiness for potential lifestyle changes. And finally, zone number 7 is an indicator of your ambitions, of what place in society you are striving to take. If your foot is completely in contact with the ground when walking, then you are determined to achieve all your life goals, your goals are objective and not contradictory.

Theoretical foundations

Dance movement therapy is based on the recognition that the body and mind are interconnected: changes in the emotional, mental or behavioral sphere cause changes in all these areas. Body and mind are seen as equal forces in integrated functioning. Dance movement therapist Berger divides psychosomatic relationships into 4 categories: muscle tension and relaxation, kinesthetics, body image, and expressive movement.

Awareness of feelings and the corresponding emotional expression involves the muscle tone of a person. People are usually not aware of their feelings if there is a high degree of bodily tension. In the process of trying to cope with stress, a person can, defending himself from fear, lose control by suppressing, repressing his feelings that exist in the body. By allowing tension to arise and keeping it in the body, one thus protects oneself from direct experience and from coming face to face with one's conflict. For example, the degree of tension in the shoulders and arms can be unconsciously increased to the point where that part of the body becomes cut off from feelings: it becomes dissociated. With such a person, the dance therapist may choose to work with a swinging arm movement to relax the muscles associated with a particular emotional state that the patient is in denial about. By starting to work with muscle patterns that correlate with emotions, a person experiences (through the muscles) feelings that are sharpened, become conscious in movement, and then recognized or clarified at a cognitive level. This connection that develops between physical action and internal emotional state is a consequence of muscle memory associated with feelings. With another client, the therapist can work with bodily sensations and translate their action in such a way that emotion and movement reinforce each other. Thus, movement becomes a direct expression of inner feelings. For clients on a more integrated level, the therapist can help focus on a specific part of the body to identify what is being done on the bodily level, perhaps unconsciously, that is causing a particular emotional experience.

With such a person, the dance therapist may choose to work with a swinging arm movement to relax the muscles associated with a particular emotional state that the patient is in denial about. By starting to work with muscle patterns that correlate with emotions, a person experiences (through the muscles) feelings that are sharpened, become conscious in movement, and then recognized or clarified at a cognitive level. This connection that develops between physical action and internal emotional state is a consequence of muscle memory associated with feelings. With another client, the therapist can work with bodily sensations and translate their action in such a way that emotion and movement reinforce each other. Thus, movement becomes a direct expression of inner feelings. For clients on a more integrated level, the therapist can help focus on a specific part of the body to identify what is being done on the bodily level, perhaps unconsciously, that is causing a particular emotional experience. In such a situation, the therapist can help the client verbally explore the associations, images, fantasies, or memories that arise in the mind in the process of connecting the motor response in the body with its emotional components.

In such a situation, the therapist can help the client verbally explore the associations, images, fantasies, or memories that arise in the mind in the process of connecting the motor response in the body with its emotional components.

Every thought, action, memory, fantasy or image causes some new muscular tension. People can be helped to discover how they change, remake, redirect, destroy or control those subtle muscle sensations that affect the experience and expression of feelings. This process is similar and corresponds to the defense mechanisms of the ego. In his work on character formation, Reich shows how an identical process becomes apparent in both the physiological and psychological realms. He's writing:

“In melancholic or depressed patients, speech and expression are frozen, as if every movement overcomes resistance. In a manic state, on the contrary, impulses suddenly cover the whole body, the whole person. In catotonic stupor, mental and muscular rigidity are identical, and only the end of this state returns both mental and muscular mobility.

To be aware of one's own feelings, some degree of body awareness is necessary. The kinesthetic process makes it possible to gain direct experience from muscular activity. Changes in body position and balance, motor coordination, and movement planning involve both the perception of external objects or events and our motor response. This kinesthetic sense, critical to the performance of daily tasks, plays a leading role in shaping our own emotional awareness and responses. There are two ways to develop emotional awareness:

The first is learning the correct label or word that corresponds to the given emotional state. This learning begins in infancy and early childhood. To understand how such learning occurs, it is enough to remember how the baby is picked up and asked: “Why are you so sad?” or say, "You're hungry, aren't you?" Our non-verbal behavior communicates, says something. Other people recognize our experiences and put them into appropriate words to identify and later talk about them.

The second way of developing emotional awareness is based on recognizing and interpreting other people's motor actions. In his study of how emotions communicate, Kline points out that each emotion has a specific psychological code and a characteristic brain pattern, controlled by the CNS and biologically coordinated, this process is the same in all people. In addition, the experience of different emotions and their corresponding muscular reactions is also universal, universal. Therefore, we are able to perceive and recognize the emotional states of others. Our emotional responses to other people usually come from our interpretations of the bodily actions and reactions of others, perceived, recognized and experienced by us on a kinesthetic level. Kinesthetic empathy, which is mostly unconscious, plays a role in verbal and non-verbal communication between people.

The next concept is the image of the body, it refers to the relationship of soul and body, that is, to the psychosomatic relationship. In one of his early summaries of body image, Schilder states: “Body image is the image of our own body that we draw in our head, i.e., this is how the body appears to us.” He considers the image of the body as something that is in a state of constant development or change. Movement causes changes in body image. The way body parts are connected, awareness of bodily sensations such as breathing, awareness of muscle activity are just a few examples of how kinesthetic sensations can contribute to awareness and development of body image. Mahler's work on emotional development and "psychological birth" also supports the notion that it is necessary to recognize the self as a separate physical reality, entity, before the process of individuation can take place.

In one of his early summaries of body image, Schilder states: “Body image is the image of our own body that we draw in our head, i.e., this is how the body appears to us.” He considers the image of the body as something that is in a state of constant development or change. Movement causes changes in body image. The way body parts are connected, awareness of bodily sensations such as breathing, awareness of muscle activity are just a few examples of how kinesthetic sensations can contribute to awareness and development of body image. Mahler's work on emotional development and "psychological birth" also supports the notion that it is necessary to recognize the self as a separate physical reality, entity, before the process of individuation can take place.

The self-image we have affects us and is influenced by all our perceptions, experiences and actions. A person who perceives himself as weak and fragile is different from one who perceives himself as strong. Just as when a child is treated like a fool, his body image will absorb his reactions to people's impressions and his own. Schilder writes:

Schilder writes:

“The positional model of our own body is related to the positional model of the body of other people. Positional models of people are interconnected. We feel the body images of other people. Experience, the experience of one's own body image and experience, the experience of the body of other people are closely intertwined. Just as our emotions and actions are inseparable from the image of the body, so the emotions and actions of others are inseparable from their bodies.

Specifically focusing on the relationship between movement change and psychological change in dance therapy, Chase states, your mental perception of yourself, attitude towards yourself”.

The fourth area that deals with the relationship of mind and body, and on which most dance therapists emphasize - expressive movement. Emotional expression is expressed through the body. Body position, gestures, breathing patterns are a few examples of movement behavior that is studied within the framework of expressive movement. It is the qualitative aspect of movement, rather how it occurs than static positions, that reflects individual self-expression. Allport and Vernon write:

It is the qualitative aspect of movement, rather how it occurs than static positions, that reflects individual self-expression. Allport and Vernon write:

"...no action can be defined as only expressive. Every action has both an inexpressive and an expressive aspect. It has... its adaptive... character as well as its individual character. Opening a door, for example, this task prescribes certain coordinated movements appropriate to this goal, but also allows a certain freedom for the individual style in performing the prescribed movements. The confidence, pressure, precision or patience with which a given task is performed has its own characteristics. Only these individual characteristics are called expressive. "

Expressive behavior is a motor manifestation of emotions interconnected in a functional system. Clines sees expressive movement as an emotional state that is expressed. His exploration of how emotions are experienced and communicated helps explain how dance movement therapy works with feelings and their manifestations in action. If we perform an action or gesture that corresponds to an emotion (eg, angrily kicking a rock), we begin to experience the corresponding visceral response generated. If this action is repeated several times, then the intensity of the emotional experience will increase. To encourage the experience and expression of emotion, the dance movement therapist works with movement patterns associated with emotion. For example, to work with anger, the therapist might suggest curling your hands into a fist, clenching them tightly, and shaking them in front of another person. There may be other instructions: to stand firmly in place, straining the whole body. In punching, the movement generates a more specific bodily experience of the emotional state. This provides feedback and a loop of interaction between expressive action and emotional experience.

If we perform an action or gesture that corresponds to an emotion (eg, angrily kicking a rock), we begin to experience the corresponding visceral response generated. If this action is repeated several times, then the intensity of the emotional experience will increase. To encourage the experience and expression of emotion, the dance movement therapist works with movement patterns associated with emotion. For example, to work with anger, the therapist might suggest curling your hands into a fist, clenching them tightly, and shaking them in front of another person. There may be other instructions: to stand firmly in place, straining the whole body. In punching, the movement generates a more specific bodily experience of the emotional state. This provides feedback and a loop of interaction between expressive action and emotional experience.

Emotions can be triggered by a real situation (eg sadness when losing a friend), perceptions of ch.-l. emotional state (e.g., being infected with fear by seeing another person's fear), in an imaginary fantasy situation (e.

+2.jpg)