How did merce cunningham influence modern dance

How Merce Cunningham reinvented the way the world saw dance

How Merce Cunningham reinvented the way the world saw dance | Dazedâ¬…ï¸ Left Arrow*ï¸âƒ£ Asteriskâ StarOption Slidersâœ‰ï¸ MailExitArt & PhotographyFeature

TextHannah Sargeant

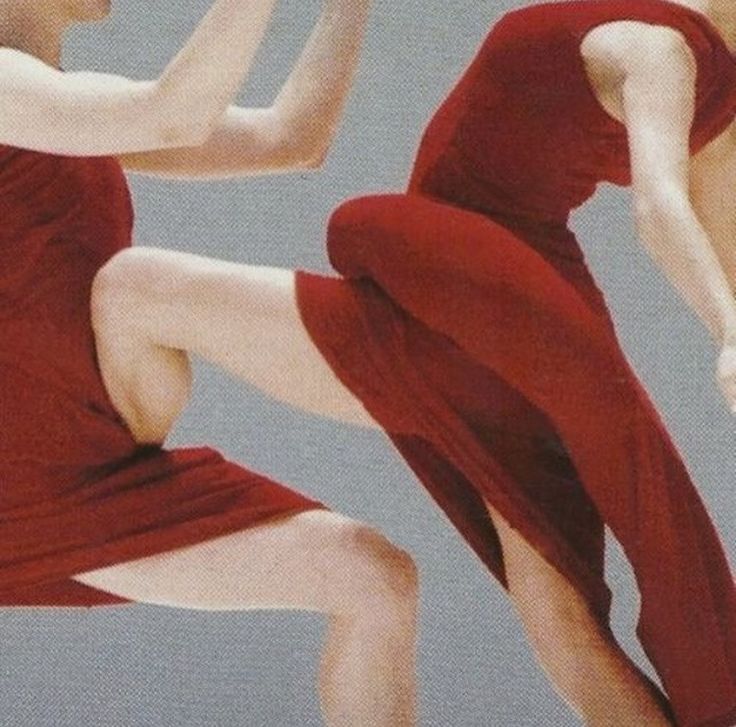

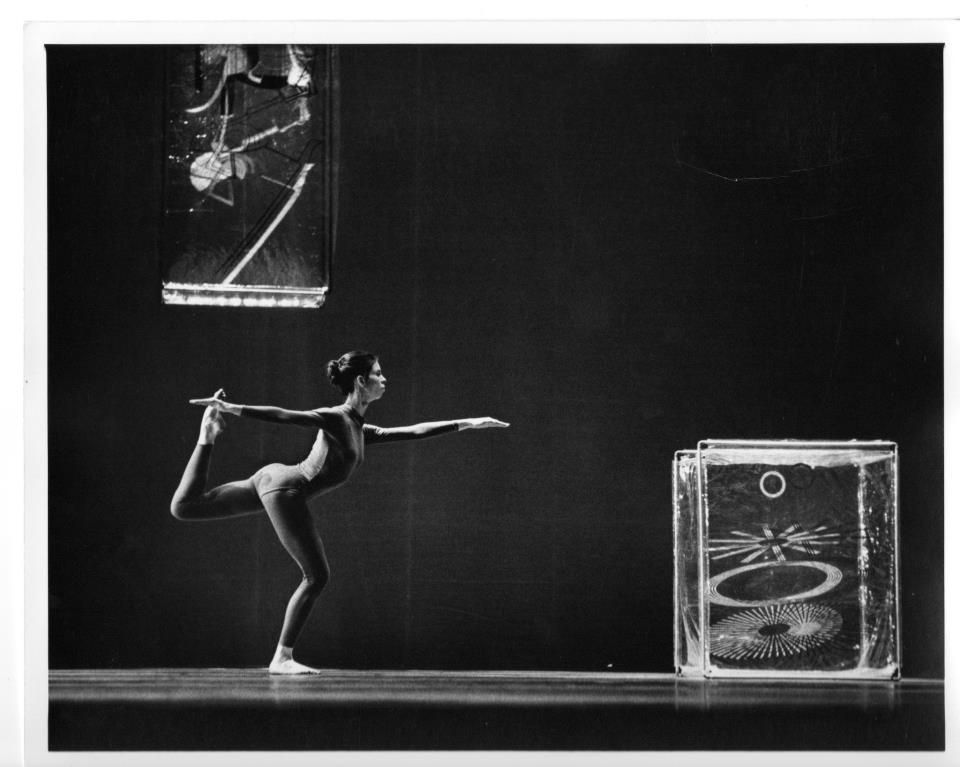

Composite image of Merce Cunningham pieces: (interior) Merce Cunningham Dance Company performing Anniversary Event during the exhibition of Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at Tate Modern in London, November 2003;a screen shot of Décor for Scramble (1967) on Event for Television, 1977. Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS)/Courtesy WNET-TV New York ArchivesArt & PhotographyFeature

Marking the centenary of his birth, we probe into the life and legacy of one of dance’s most celebrated and avant-garde trailblazers

TextHannah Sargeant

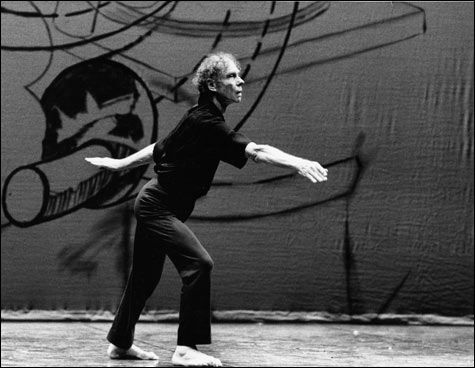

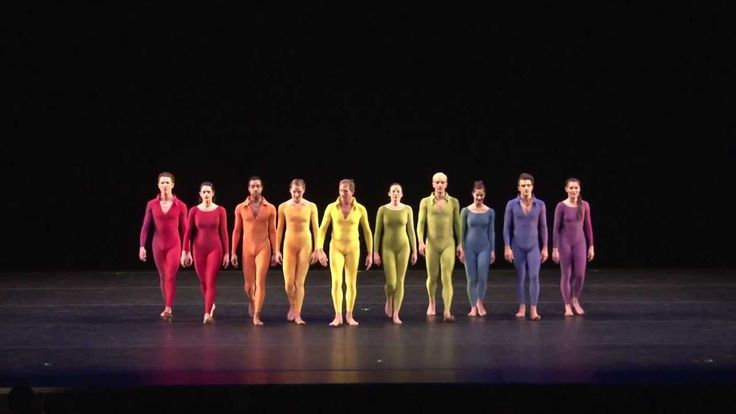

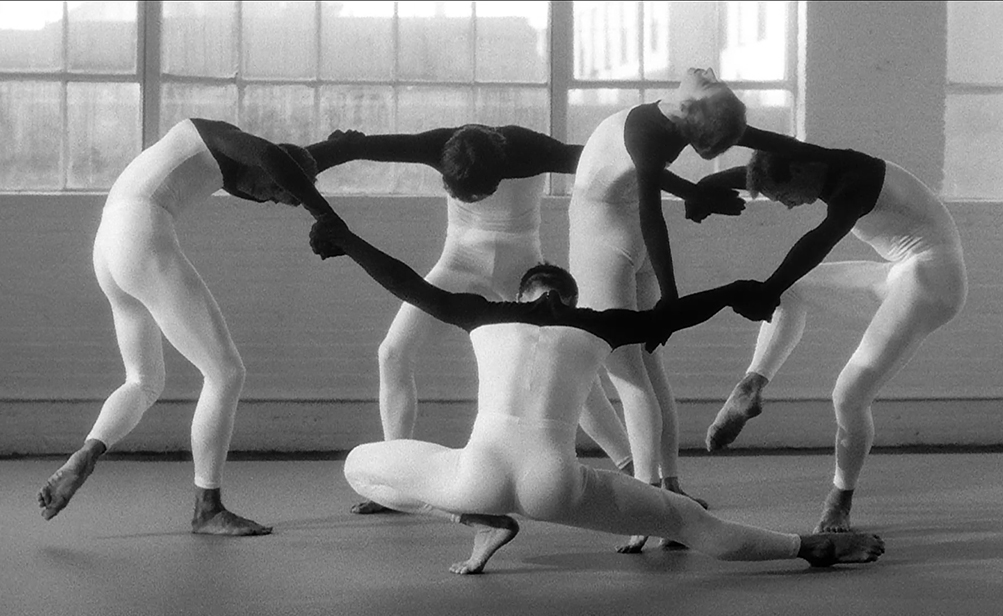

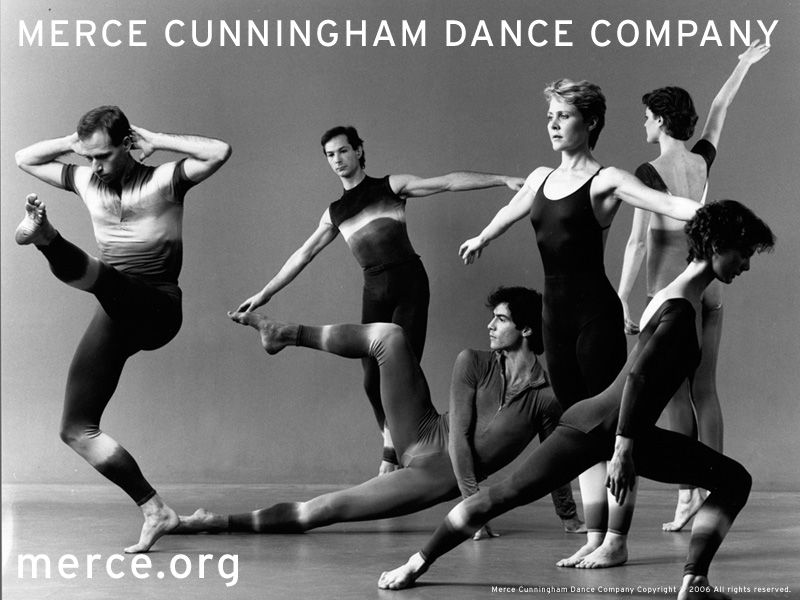

Merce Cunningham was an exceptionally good dancer. Better yet, he was an incredibly accomplished master of modern choreography, with a prolific roster of over 150 dances and 800 of what he called dance ‘events’ attached to his name. As a perennial collaborator, his work reached high acclaim as he produced performances alongside artistic visionaries and musicians like Robert Rauschenberg, Brian Eno, Roy Lichtenstein, Radiohead, Rei Kawakubo, and Jasper Johns. Ultimately, he was known for filling the void that lay between dance and the rest of the art world, without ever compromising on the power of each discipline in their separate forms.

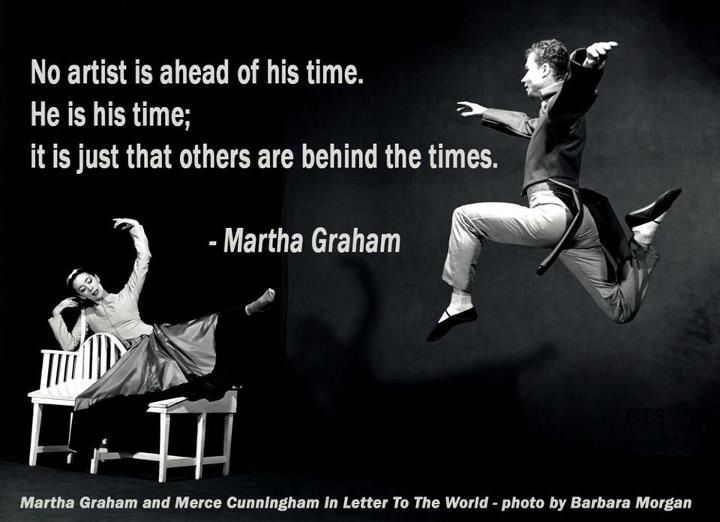

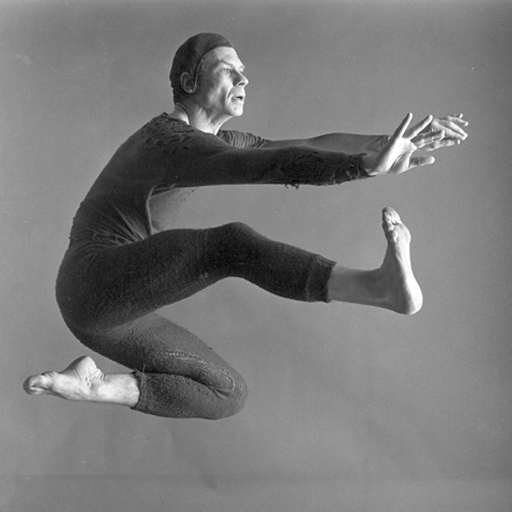

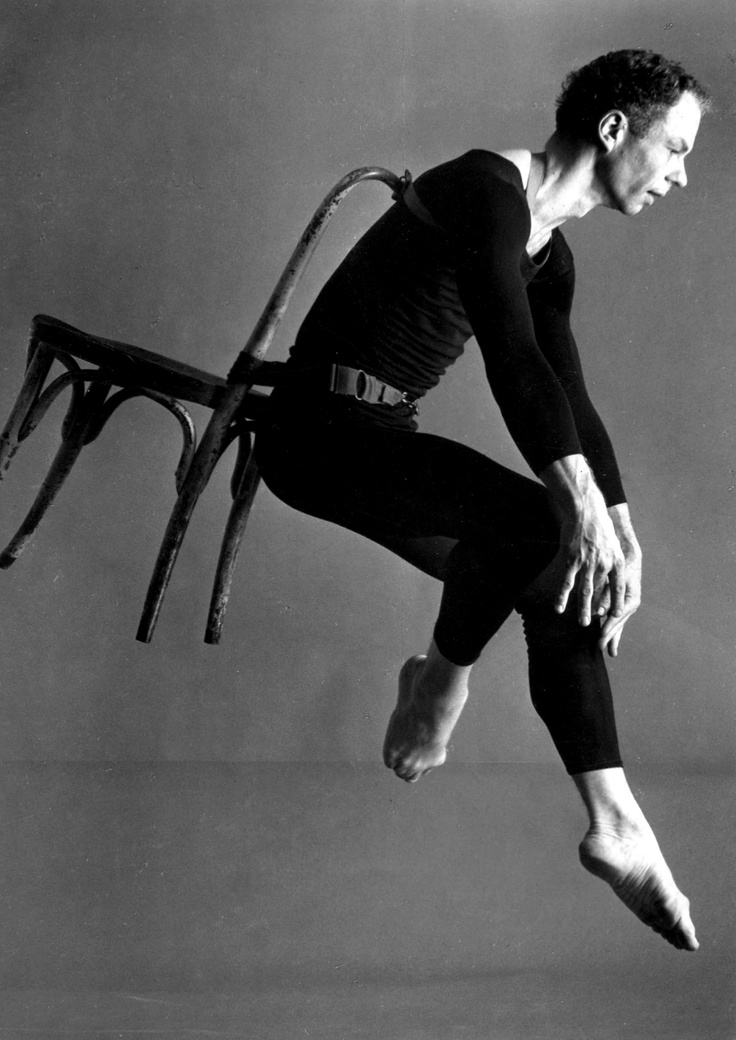

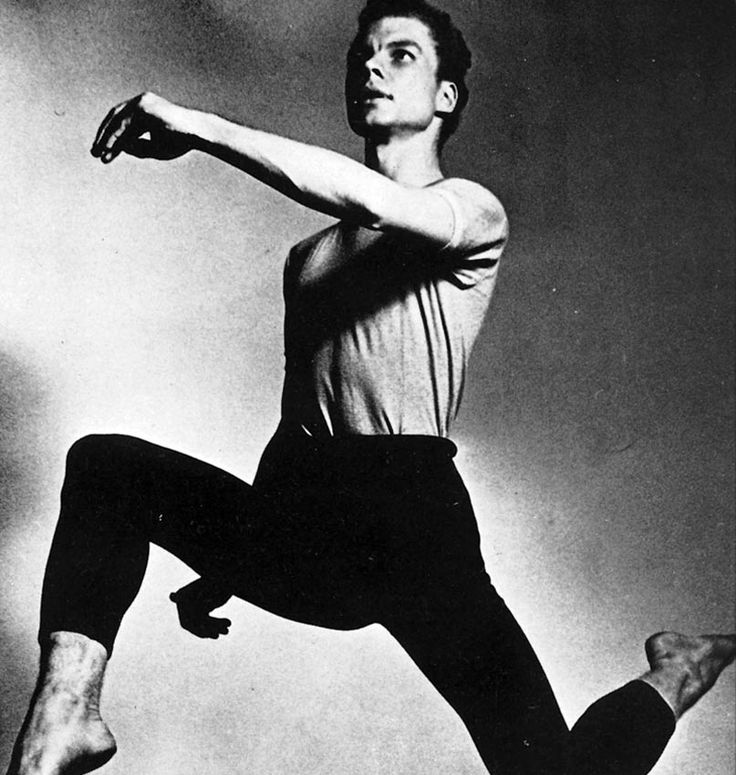

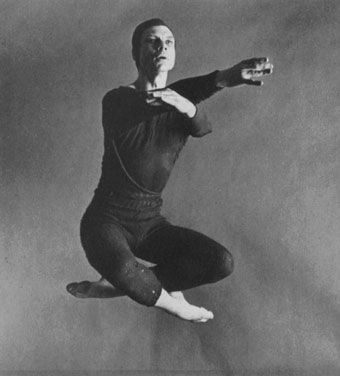

Born in Centralia, Washington, in 1919, Cunningham’s talent and powerful leaps saw him join the Martha Graham Dance Company at the age of 20 before going on to work on his own terms. Later he met who would become his partner, John Cage, who was arguably the most important chess piece in Cunningham’s life and work.

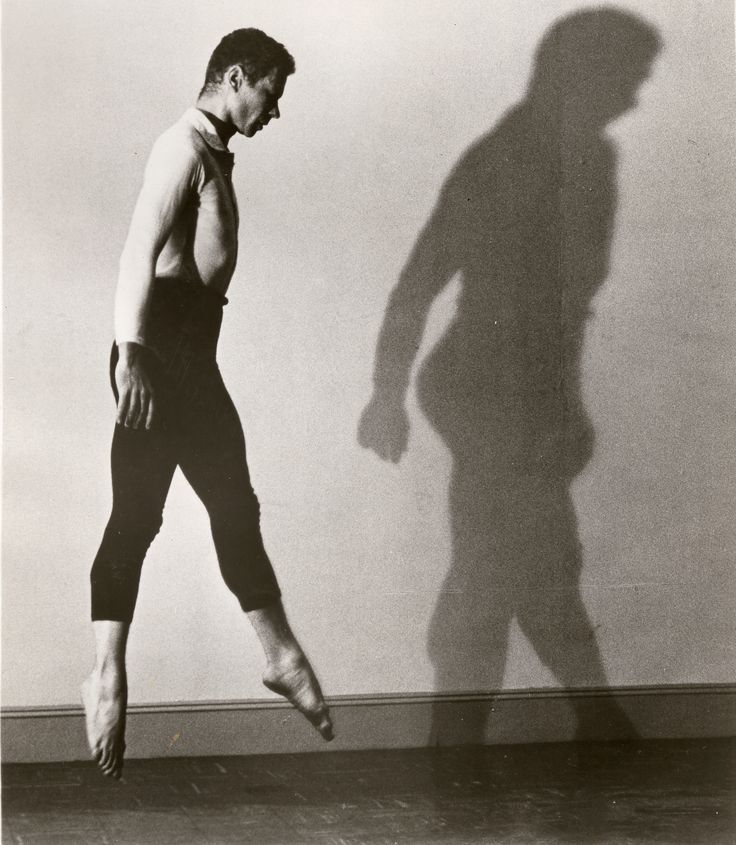

Cunningham didn’t always have much to say and didn’t care a lot for what things meant – to himself or the rest of the world. Rather, he was a man of action; a mover. Direct and unmediated, he listened to his influences of Zen, ballet, and art. And without complication or high-flown explanations, he continued to create something totally new throughout a career that spanned over 70 years.

Rather, he was a man of action; a mover. Direct and unmediated, he listened to his influences of Zen, ballet, and art. And without complication or high-flown explanations, he continued to create something totally new throughout a career that spanned over 70 years.

Today is what would have been Cunningham’s 100th birthday, and while many important choreographers seem to fall by the wayside unless you’re especially well informed in dance and its theory, Cunningham made a point of documenting and preserving his contributions – perhaps partly so that they could be celebrated on days like these. In his memory, we revisit the life of one of dance’s biggest pioneers of chance and vanguards of modern movement.

“Cunningham didn’t always have much to say and didn’t care a lot for what things meant – to himself or the rest of the world. Rather, he was a man of action; a mover”

Read More

Photos that capture the white-hot heat of adolescence

Sensuality, psychedelia, and spells: exploring the history of plant magic

This dreamy photo book reimagines divine beings

6 fetishists debunk the kink scene’s biggest myths

HIS APPROACH TO DANCE WAS RADICAL AND NEOTERICWhile the rest of the world was dancing to a beat, tune, or rhythm, Cunningham was sinking his heels into the sporadic, the unsystematic, and the unpredictable. His signature methods included what has been termed as ‘choreography by chance’, with sequences of movements sometimes determined on the night of performances by the tossing of a coin. The composer Morton Feldman, who wrote the score for Summerspace, described Cunningham’s method: "Suppose your daughter is getting married and her wedding dress won't be ready until the morning of the wedding, but it's by Dior."

His signature methods included what has been termed as ‘choreography by chance’, with sequences of movements sometimes determined on the night of performances by the tossing of a coin. The composer Morton Feldman, who wrote the score for Summerspace, described Cunningham’s method: "Suppose your daughter is getting married and her wedding dress won't be ready until the morning of the wedding, but it's by Dior."

It was part of his artistic process that himself and his dancers would not rehearse to the music in advance, and often the music and the set would be created without the knowledge of the dance itself – the end results just as unknown to his dance company as it would have been to his audience. Cunningham himself once said, “It is hard for many people to accept that dancing has nothing in common with music other than time and the division of time.” By intentionally separating two things that had been so incessantly linked throughout history, Cunningham reinvented the wheel, not only in terms of choreography, but also in how it was performed in the moment and received by those who experienced it. It certainly took many of Cunningham’s spectators and critics time to warm up to Cunningham’s initial introduction to his ultra-modern style, but never faltering, he continued this methodology almost religiously throughout the rest of his career.

It certainly took many of Cunningham’s spectators and critics time to warm up to Cunningham’s initial introduction to his ultra-modern style, but never faltering, he continued this methodology almost religiously throughout the rest of his career.

Cunningham’s experimentation with breaking down the boundaries between various forms of art and philosophy was revolutionary during the 1940s and early 50s. One of the most notable elements of his work was how he incorporated the forms of dance, music, and visuals through artistic collaboration. What was key, though, was that his trusted collaborators understood him, and trusted him back. The ongoing uncertainty of Cunningham’s working process was no doubt then eased by the fact that most of his collaborators were around for the long haul, often working alongside each other over periods of years and in some cases, decades.

The dance piece, Rainforest, that saw David Tudor responsible for the electronic score and Andy Warhol create the set design was choreographed by Cunningham back in 1968; a momentous year remembered for its student revolts and public social rebellion. Warhol created large silver pillows filled with helium that floated freely over the performance, uncontrollable and anarchic. In an open-air performance of the piece, some of the pillows blew away totally, an unprecedented event that was literally and metaphorically out of their hands. What Cunningham, Warhol, and many of Cunningham’s artistic and philosophic collaborators had was a common ground, where dance theory, art, ancient mantras, and modernist attitudes could come together, both exclusively and as one.

HE WAS IMPATIENT WITH THE IDEA OF HIS PERFORMANCES HAVING A ‘MEANING’When once asked what one dance was about, he answered: "it's about 40 minutes". As a rebel against the status quo of the choreography that came before him, he rebuffed typical use of narrative, structure, and expression, and led the way with his ‘pure movement’ ethos. Some might translate this as a parallel to “art for art’s sake”; an approach to dance that many saw as an adventure out onto previously untrodden land. Most of all, he rejected the idea of dance needing to be justified by any specific point or explanation. As far as Cunningham was concerned, all connotations and perceptions were valid reactions, and none more valid than the other.

As a rebel against the status quo of the choreography that came before him, he rebuffed typical use of narrative, structure, and expression, and led the way with his ‘pure movement’ ethos. Some might translate this as a parallel to “art for art’s sake”; an approach to dance that many saw as an adventure out onto previously untrodden land. Most of all, he rejected the idea of dance needing to be justified by any specific point or explanation. As far as Cunningham was concerned, all connotations and perceptions were valid reactions, and none more valid than the other.

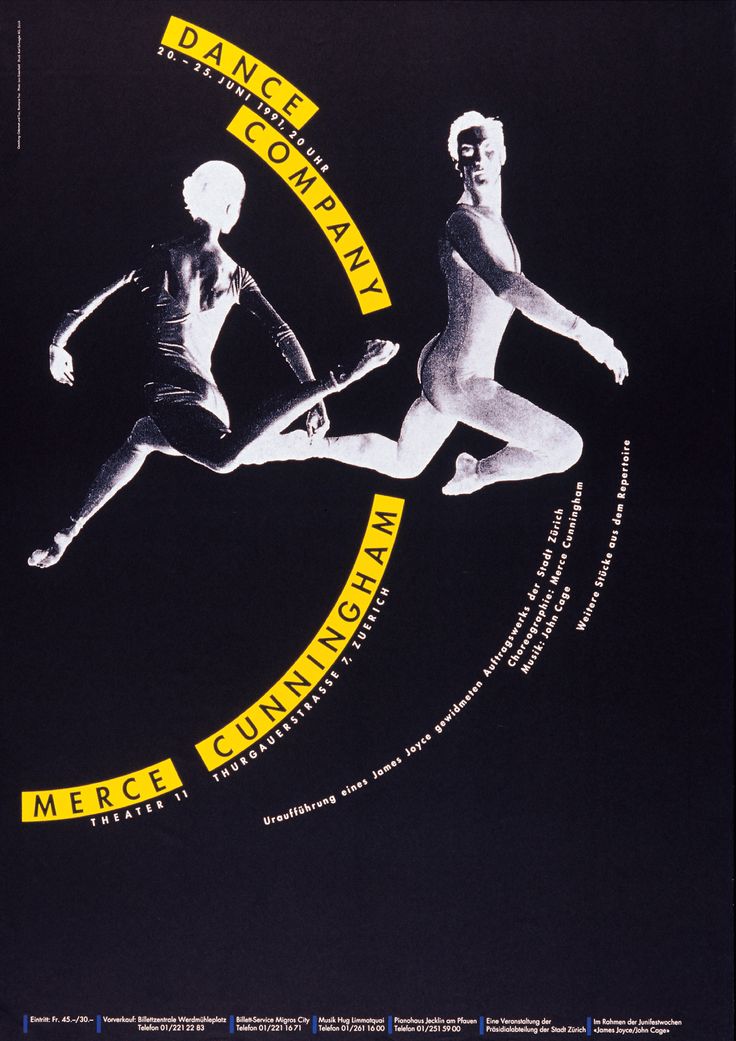

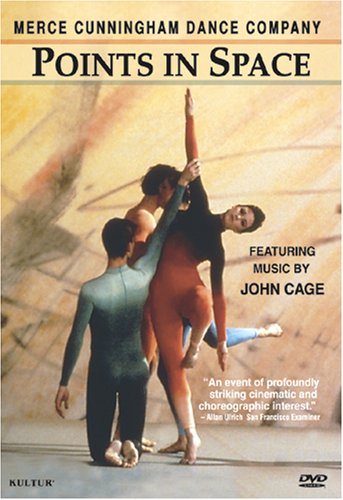

Many know of Cunningham and his work through his working and romantic connection to John Cage – it’s a rare occasion to come across their names in a sentence without one or the other. As a prominent American composer, Cage pioneered the use of ‘chance composition’ and indeterminacy in music, which allowed for the freedom of the audience’s perception, and extended technique; the practice of playing instruments in unconventional ways to achieve strange and irregular sounds. Many have noted Cage as one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde, so it’s no wonder that the Cage-Cunningham duo was so compatible, as two names working synonymously in time with each other. Despite their synchronicity and some of Cunningham’s most celebrated works coming from their collaboration, they both famously asserted that music and dance should co-exist but not be intentionally coordinated, with the only common denominators being time and rhythmic structure.

Many have noted Cage as one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde, so it’s no wonder that the Cage-Cunningham duo was so compatible, as two names working synonymously in time with each other. Despite their synchronicity and some of Cunningham’s most celebrated works coming from their collaboration, they both famously asserted that music and dance should co-exist but not be intentionally coordinated, with the only common denominators being time and rhythmic structure.

When Cunningham first met Cage in his late teens, Cage was playing an accompaniment for a class in Seattle where Cunningham danced. Fast-forward to the 1940s in New York, and the pair were working together on their first collaboration, for which Cunningham was choreographing the dance and Cage writing the music separately. At this point, their conversation of a piece where music and dance were not dependent on one another was already well into the throes of its development, and this concept swiftly became the basis of almost all of Cunningham’s work. Cunningham may have said that dance and music had barely anything in common, but these two were quite obviously striding down the same garden path in their thinking.

Cunningham may have said that dance and music had barely anything in common, but these two were quite obviously striding down the same garden path in their thinking.

Beyond the realms of their working relationship, the romantic ties between Cunningham and Cage as lovers and life partners further married their collective works and mantras in art and in life. Cunningham was likely to have come across I Ching after its first translation into English was published in the US in 1951, and alongside Cage (of whom I Ching had a hugely notable impact), he regularly consulted the ancient Chinese text to guide his choreography. The idea of escaping patterns of thought, was for both of them, of paramount importance. With narrative and classical structures out of the window, Cunningham was relying on pure stochasticity to inform his ‘events’ and free himself of cliché. Despite the intention of freeing his thinking, Cunningham’s pre-performance I Ching consultations were thorough and meticulous, but worth it for the occasional moments of wonder and surprise that they would conjure.

In many ways, Cunningham owed his concept of ‘pure movement’ to the philosophies of Buddhism and Zen; especially exercising discipline and removing emotion and expression from the mix. His critics sometimes blasted him for not talking much about his work. But Cunningham was a man of direct action, and unlike many other forms of art that leave behind a physical record such as a book, a painting or a script, Cunningham understood that he was working in the momentary. In an interview with Peter Dickinson, however, Cunningham did touch on his appreciation for Zen and how it had impacted him. He said, “I happened to read this quotation of Einstein’s where he said there are no fixed points in space. I thought that was perfect for the stage, and there’s no point that’s any more important than any other. In that sense, it’s Buddhist or Zen. Any point could be important. Wherever anybody was, was in that sense a centre.”

HE COLLABORATED WITH ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ON OVER 20 WORKS“Cunningham reinvented the wheel, not only in terms of choreography, but also in how it was performed in the moment and received by those who experienced it”

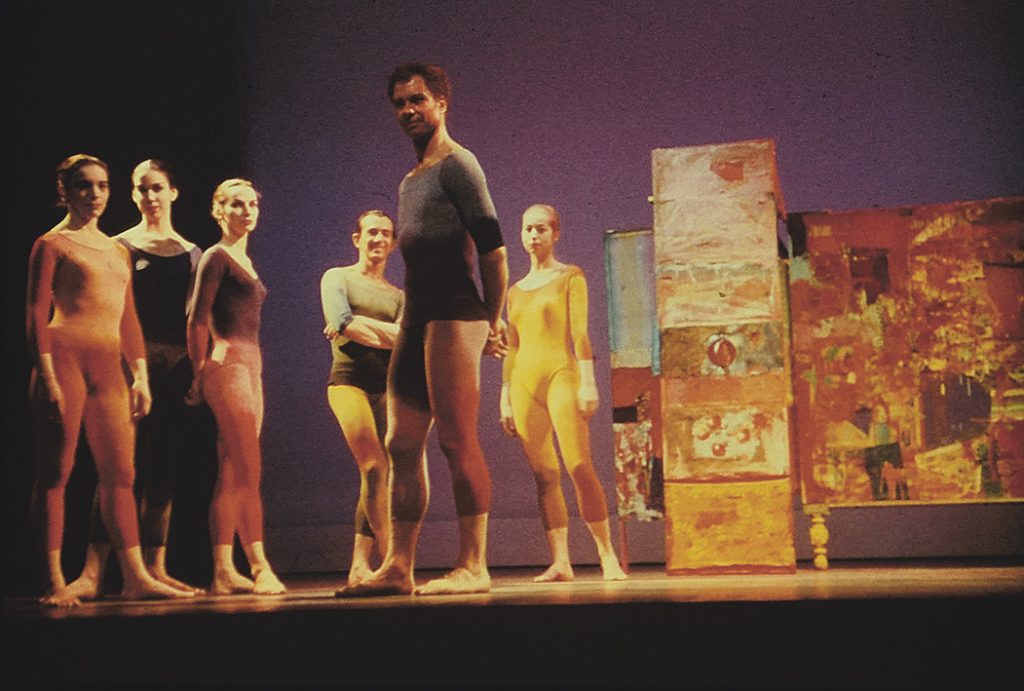

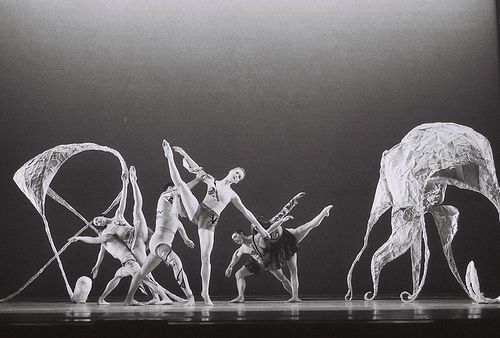

The ongoing collaborative relationship between Cunningham and Rauschenberg saw them work together over the span of a decade from 1954 to 1964, where Rauschenberg created endless costumes, props, lighting, and set designs. Dance Works I is one of the best examples of Cunningham’s penchant for collaboration; a piece that featured enormous curtains painted by Rauschenberg and large scale sculptural pieces, as well as the slightly translucent, black and white collage curtains that he made for Cunningham’s Interscape, which allowed the audience to see the dancers warming up on stage.

Dance Works I is one of the best examples of Cunningham’s penchant for collaboration; a piece that featured enormous curtains painted by Rauschenberg and large scale sculptural pieces, as well as the slightly translucent, black and white collage curtains that he made for Cunningham’s Interscape, which allowed the audience to see the dancers warming up on stage.

Just like the working dynamic with Cage, Cunningham and Rauschenberg disjointed the connection between dance and visuals, allowing both to create independently, and with minimal knowledge of what the other was doing. Quite often, Cunningham would only allude figurative clues about what he was going for on his end. During the production of Winterbranch in 1964, for example, Cunningham told Rauschenberg ambiguously to “think of the night as if it were day”. In response, Rauschenberg’s visuals consisted of all-black costumes and sudden, bright headlight-like lighting that had the audience shielding their eyes while the dancers on stage were engulfed in darkness. Filmmaker Charles Atlas recalled the performance: “There were battery-operated lights held by various people in the wings, and the lighting design was very erratic. It had nothing to do with the dance.”

Filmmaker Charles Atlas recalled the performance: “There were battery-operated lights held by various people in the wings, and the lighting design was very erratic. It had nothing to do with the dance.”

Cunningham, Cage, and Rauschenberg often worked all together on the same pieces – although their idea of “working together” was in fact a fragmented, exclusive process. Rauschenberg’s position as a long-standing collaborator came to an end with the 1964 world tour, after Rauschenberg commented egotistically that the Merce Cunningham Dance Company was his “biggest canvas”, a comment that was construed as the colonisation of a relationship that was supposed to be all about independence.

Merce Cunningham Dance Company performing Interscape (2000), with costumes and décor by Robert RauschenbergCourtesy Walker ArtFORWARD-THINKING WAS KEY

In an interview with the Cunningham near the end of his life, Judith Mackrell observed that he seemed “bent on reinventing himself until the last”. Spending 90 years throughout one of the most transitory and shifting centuries in history saw him experience a multitude of new schools of thought and attitudes. He was forever looking ahead, adapting to the times, looking to utilise new change. Later in his career, he experimented with motion technology and an animated computer program called DanceForm in his choreography, and near his death, he created a ‘Legacy Plan’ with digital archives preserving his work and information on how he wished his company to be run after his death. Cunningham also set up the Merce Cunningham Trust in 2000; maintaining and enhancing his life work and protecting the public’s access to it.

Spending 90 years throughout one of the most transitory and shifting centuries in history saw him experience a multitude of new schools of thought and attitudes. He was forever looking ahead, adapting to the times, looking to utilise new change. Later in his career, he experimented with motion technology and an animated computer program called DanceForm in his choreography, and near his death, he created a ‘Legacy Plan’ with digital archives preserving his work and information on how he wished his company to be run after his death. Cunningham also set up the Merce Cunningham Trust in 2000; maintaining and enhancing his life work and protecting the public’s access to it.

Cunningham was a fearless innovator and marched ahead of the others for seven whole decades. When others seemed put off or confused by the irregularity and absence of resolution in his choreography, Cunningham just carried on doing it anyway. As the famed ballet dancer and choreographer, Mikhail Baryshnikov, said, “Merce Cunningham reinvented dance, and then waited for the audience”. Recognition for being boundless and state-of-the-art was achieved relatively early on in his career, but it was the opening up of limits and constraints in dance that had the biggest impact of all, on his contemporaries and those who continue to find incentive and experimentation through his work today.

Recognition for being boundless and state-of-the-art was achieved relatively early on in his career, but it was the opening up of limits and constraints in dance that had the biggest impact of all, on his contemporaries and those who continue to find incentive and experimentation through his work today.

Art & PhotographyFeatureDanceArt

Merce Cunningham | Biography, Dance, & Facts

Merce Cunningham

See all media

- Born:

- April 16, 1919 Centralia Washington

- Died:

- July 26, 2009 (aged 90) New York City New York

- Awards And Honors:

- Praemium Imperiale (2005)

- Subjects Of Study:

- “Cunningham”

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

Learn about the dances choreographed by Merce Cunningham such as John Cage's Roaratorio and David Tudor Sounddance, both inspired by the Irish author James Joyce

See all videos for this articleMerce Cunningham, (born April 16, 1919, Centralia, Washington, U. S.—died July 26, 2009, New York, New York), American modern dancer and choreographer who developed new forms of abstract dance movement.

S.—died July 26, 2009, New York, New York), American modern dancer and choreographer who developed new forms of abstract dance movement.

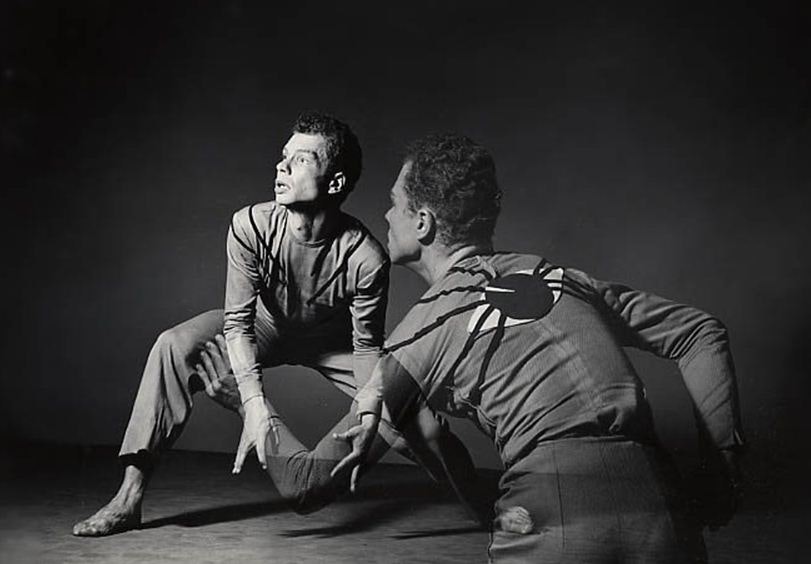

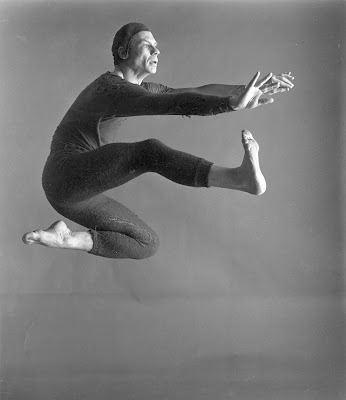

Cunningham began to study dance at 12 years of age. After high school he attended the Cornish School of Fine and Applied Arts in Seattle, Washington, for two years. He subsequently studied at Mills College (1938) with dancer and choreographer Lester Horton and at Bennington College (1939), where he was invited by Martha Graham to join her group. As a soloist for her company, he created many important roles, and his incredible jumps were showcased in Graham’s “El Penitente” (1940), “Letter to the World” (1940), and “Appalachian Spring” (1944).

More From Britannica

dance: Merce Cunningham

Encouraged by Graham, Cunningham began to choreograph in 1943. Among his early works were Root of an Unfocus (1944) and Mysterious Adventure (1945). Increasingly involved in a relationship with the composer John Cage, Cunningham started collaborating with him, and in 1944 he presented his first solo concert, with music by Cage. After leaving Graham’s company in 1945, Cunningham worked with Cage on numerous projects. They collaborated on annual recitals in New York City and on a number of works, such as The Seasons (1947) and Inlets (1978). In 1953 Cunningham formed his own dance company.

After leaving Graham’s company in 1945, Cunningham worked with Cage on numerous projects. They collaborated on annual recitals in New York City and on a number of works, such as The Seasons (1947) and Inlets (1978). In 1953 Cunningham formed his own dance company.

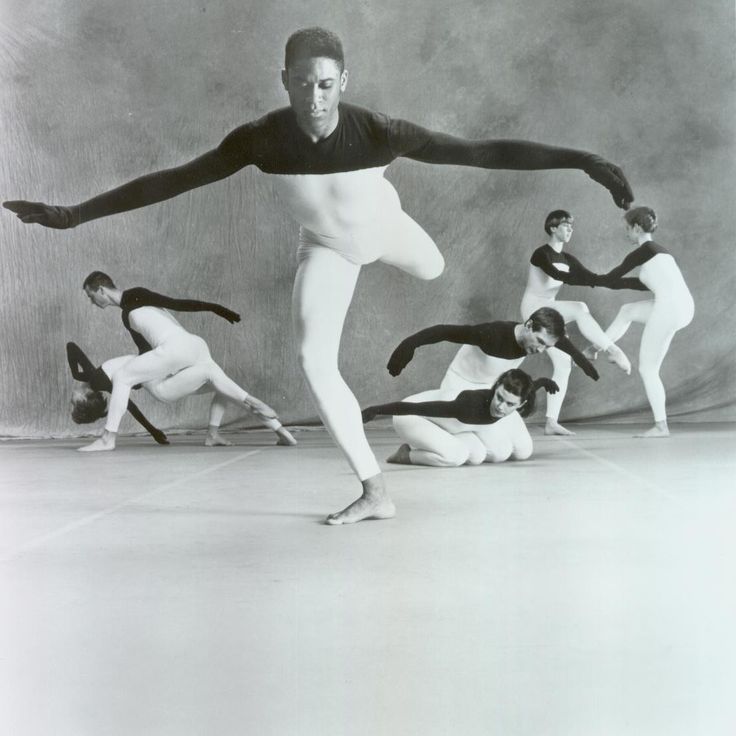

Like Cage, Cunningham was intrigued by the potential of random phenomena as determinants of structure. Inspired also by the pursuit of pure movement as devoid as possible of emotional implications, Cunningham developed “choreography by chance,” a technique in which selected isolated movements are assigned sequence by such random methods as tossing a coin. The sequential arrangement of the component dances in Sixteen Dances for Soloist and Company of Three (1951) was thus determined, and in Suite by Chance (1953) the movement patterns themselves were so constructed. Suite by Chance was also the first modern dance performed to an electronic score, which was commissioned from American experimental composer Christian Wolff. Symphonie pour un homme seul (1952; later called Collage) was performed to Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry’s composition of the same name and was the first performance in the United States of musique concrète, or music constructed from tape-recorded environmental sounds.

Symphonie pour un homme seul (1952; later called Collage) was performed to Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry’s composition of the same name and was the first performance in the United States of musique concrète, or music constructed from tape-recorded environmental sounds.

Cunningham’s abstract dances vary greatly in mood but are frequently characterized by abrupt changes and contrasts in movement. Many of his works have been associated with Dadaist, Surrealist, and Existentialist motifs. In 1974 Cunningham abandoned his company’s repertory, which had been built over a 20-year period, for what he called “Events,” excerpts from old or new dances, sometimes two or more simultaneously. Choreography created expressly for videotape, which included Blue Studio: Five Segments (1975–76), was still another innovation. He also began working with film and created Locale (1979). Later dances included Duets (1980), Fielding Sixes (1980), Channels/Inserts (1981), and Quartets (1982).

When arthritis seriously began to disrupt his dancing in the early 1990s, Cunningham turned to a special animated computer program, DanceForms, to explore new choreographic possibilities. Although he left the performance stage soon after Cage died in 1992, he continued to lead his dance company until shortly before his own death. In 2005 he received the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale prize for theatre/film. To mark Cunningham’s 90th birthday, the Brooklyn Academy of Music premiered his new and last work, Nearly Ninety, in April 2009. His career was the subject of the documentary Cunningham (2019).

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaThis article was most recently revised and updated by Amy Tikkanen.

Merce Cunningham - frwiki.wiki

For articles of the same name, see Cunningham.

The essence of this biographical article is to check ( ).

Improve it or discuss what needs to be checked. If you have just pasted a banner, indicate what to check here .

Mercier Cunningham, known as Mercier Cunningham , born in Centralia in Washington State, in the United States and died in New York - US dancer and choreographer. His work has contributed to the renewal of dance thinking throughout the world. He is considered a choreographer who made the conceptual transition from modern dance and modern dance, in particular by separating dance from music, and integrating some randomness into the unfolding of his choreography.

Summary

- 1 Biography

- 1.1 Use case

- 1.2 Contribution to motion recording software

- 2 Theory

- 3 Influence in the world of contemporary dance

- 4 Basic choreographies

- 5 Differences

- 6 applications

- 6.

1 Bibliography

1 Bibliography - 6.2 Filmography

- 6.3 External links

- 6.

- 7 Notes and references

biography

Mercier Philip Cunningham, known as Merce Cunningham, is part of an artistic movement, contemporary art, that has influenced the world of fine art, music and, to a lesser extent, the world of dance.

Merce Cunningham began his dancing career with Martha Graham, one of the greatest figures in what was then called "modern dance". Therefore, it is in this context that Cunningham, encouraged by his companion, the composer John Cage, composes his first works. He left Graham's company in 1945 and recorded his first solos. In 1953 he founded his Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MVDC) at Black Mountain College. In 2002, Merce Cunningham received the Nijinsky Prize in Monaco for his entire career, awarded by Robert Rauschenberg.

Use of Chance

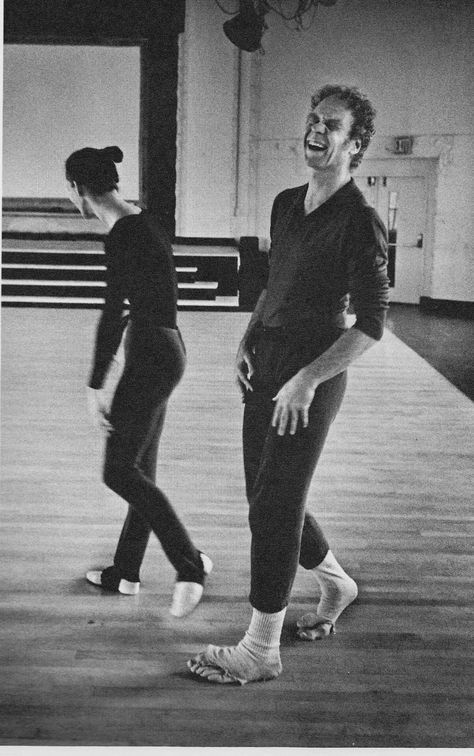

Cunningham in 1972

In 1951, his 16 Dances for Soloist and Company of Three marked the first step in a direction other than a return to the deeper self. Cunningham uses chance (or chance) to compose this dance: he tosses coins to determine the order of the parts of the dance. The use of chance allows him to make aesthetic decisions objectively and impersonally. It can be said that this means of achieving creation, and not intuition, instinct or personal taste, was a kind of point of no return in Cunningham's choreographic concept.

Cunningham uses chance (or chance) to compose this dance: he tosses coins to determine the order of the parts of the dance. The use of chance allows him to make aesthetic decisions objectively and impersonally. It can be said that this means of achieving creation, and not intuition, instinct or personal taste, was a kind of point of no return in Cunningham's choreographic concept.

The idea of using random processes to compose was pioneered by composer John Cage, a companion of Cunningham for over fifty years before his death in 1992. The circle of artists revolving around Cage and Cunningham included visual artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, composers such as Earl Brown, Morton Feldman, David Tudor, and many others. All of these artists were people deeply rooted in their time. It can be said that they are "urban" artists who do not turn away from the sound and visual impressions emanating from urban life, nor from the technological innovations of their time.

Thus, as in life, dance, music, plasticity coexist in Cunningham's choreography, each of which works on its own, and is superimposed on the day of the performance on an open artistic meeting. Cunningham wants one form not to dominate another on the stage, but to form a whole.

Why do these works use randomness? It is a way to surprise yourself, to go beyond your own ego, to get out of the way.

The purpose of Cunningham's dance is to show movement and its organization in space and time. There is no hidden meaning in Cunningham's choreography and everyone has to find their own way in their work. The spectator is called to be active, since no significance is attached to him, he is free to see or hear what he wants, according to his own desire. It can be said that Cunningham's dance will be a dance of the intellect, as opposed to the dance of the emotions of modern dance. This is a modest dance that holds back emotions. Everyone is free to enjoy these collage games created by Cunningham and his team.

Apart from chance, Cunningham pays special attention to time. This is no longer the time of the music we follow, measured by a measure, but the time of a stopwatch. Dance sequences have such and such duration. Each cell has its own musicality in its relationship of movement with each other and with others. Musicality is internal to the movement, and the one who dances it is not imposed from outside.

Attitude towards space is also very specific. This is no longer a prospect. Each dancer is his own center. Space is created and destroyed, poking around in front of the audience, freely choosing what interests them, instead of fixing the lead dancer in the center of the stage.

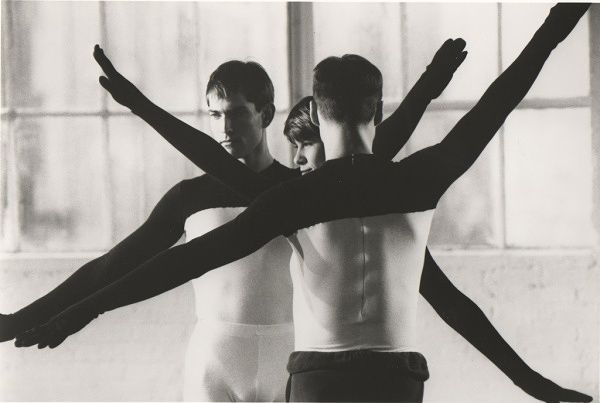

In terms of movement technique, Cunningham uses foot movements that are close to classical in form, but the intent and energy that animate them are in a different register, especially since there is an addition back. movements chosen at random and using it in all possible directions: forward, backward, sideways, diagonally forward and backward. ..

..

So dancing with Merce Cunningham requires great mental readiness, mastery of your soft body, you must always have an alert mind to dance this dance. Moreover, in this regard, it is difficult to say that Cunningham's dance is abstract, because it is a body that is widely used in its possibilities, including in its relation to the mind.

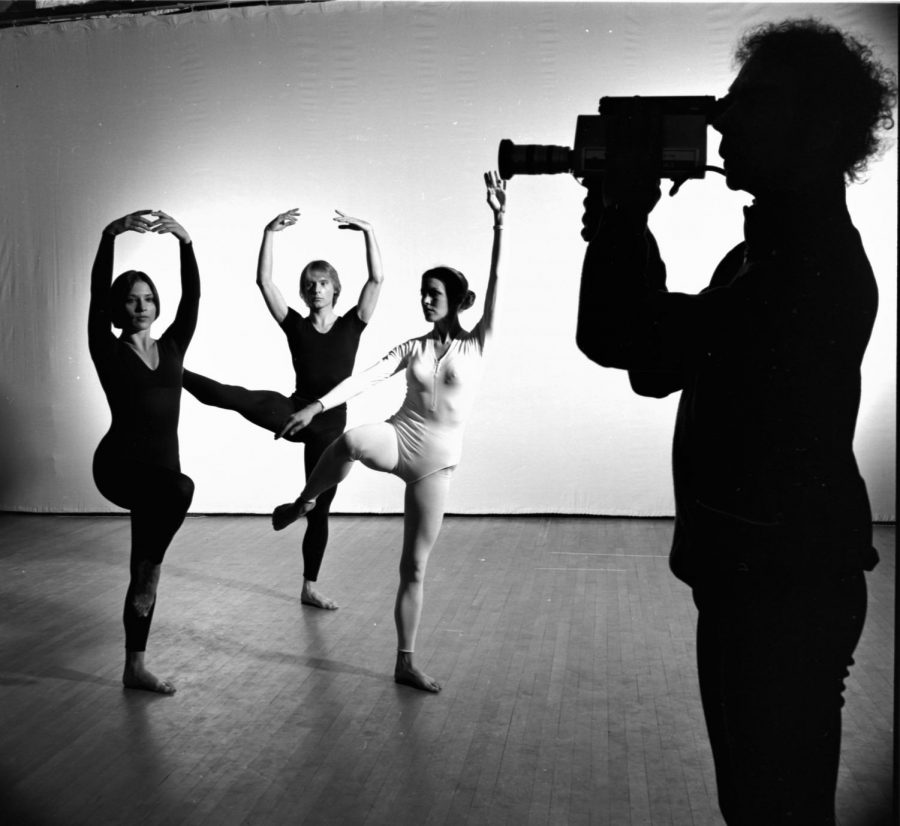

Cunningham was one of the first choreographers to use the camera to film the dance, not as a witness to the work, but as a visual object in itself.

Contribution to the creation of motion writing software

In 1989, Merce Cunningham collaborated with computer science researchers at Simon Fraser University in the USA to create software called "Life Forms" for writing choreographic movements. This software performs three roles. The first is the ability to record exercises or sequences from computerized choreographic cells, replacing choreological notation. The second is to create from this data the original and random choreography that forms the basis of Cunningham's historical work. Finally, the third is the creation of images from motion sensors placed on the dancers and processed by computers.

Finally, the third is the creation of images from motion sensors placed on the dancers and processed by computers.

For Merce Cunningham, this software represents a meeting between the binary logic of computer science, the scientific theories developed by modern physics, and the theories developed by the philosophical thought of I King. An emblematic sight of the use of this software in the making is the Biped , created in 1999.

Theory

It is with Merce Cunningham that the problems of modern dance begin to arise. There is no longer a common thread, no longer necessarily a story. He was quickly joined by John Cage, he will go deep into the movement and break the codes of the stage: all points of space have the same value, why is this a binary relationship between dance and music, each dancer is a soloist, and he is not. no longer a choir and the only soloist… He is at the crossroads between modern and post-modern dance and does not fit into either of these two categories. His work will be used in postmodern dance to set it in motion or continue, with the idea that all movements are of equal value. Merce Cunningham tries to get rid of body coordination and randomly moves the elements and directions of the body. Then he experiences unknown movements. We live in 1948 with Untitled Solo . This is a rather vertical dance that breaks the movement of the strong axis of the column. It is more like a figure than energy circulating in the body. Creative interest lies in the path leading from one figure to another. This work on random leads him to turn to computer scientists and create Lifeform , a program that creates and simulates random movements in random order as a small virtual character. The problem of falling followed by a jump sums up the complexity of the implementation, and even these errors are accepted. Likewise, he has his team work separately on music, costumes, and eventual lighting, and brings them all together on the day of the show.

His work will be used in postmodern dance to set it in motion or continue, with the idea that all movements are of equal value. Merce Cunningham tries to get rid of body coordination and randomly moves the elements and directions of the body. Then he experiences unknown movements. We live in 1948 with Untitled Solo . This is a rather vertical dance that breaks the movement of the strong axis of the column. It is more like a figure than energy circulating in the body. Creative interest lies in the path leading from one figure to another. This work on random leads him to turn to computer scientists and create Lifeform , a program that creates and simulates random movements in random order as a small virtual character. The problem of falling followed by a jump sums up the complexity of the implementation, and even these errors are accepted. Likewise, he has his team work separately on music, costumes, and eventual lighting, and brings them all together on the day of the show. Therefore, he breaks dance-music associations and works on duration. From Biped in 1999 he delivered Lifeform software for the first time.

Therefore, he breaks dance-music associations and works on duration. From Biped in 1999 he delivered Lifeform software for the first time.

Influence in the world of contemporary dance

A large number of dancers who have passed through Cunningham's studio have formed their own dance company, notably Paul Taylor, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, Carole Armitage, Dominique Bagouet, Angeline Preljocage, Jean-Claude Gallotta, Philippe Decoufle, Floanne. Ankah, Fufwa from Stillness, Ann Papoulis, Kimberly Bartosik and Jonah Bokaer.

Basic choreography

- 1944 : Defocus Root

- 1948: Untitled solo

- 1951 : 16 dances for soloist and troupe of three

- 1956: Suite for five

- 1956: Substitution

- 1958: Summer Space

- 1958: Antic Meet

- 1960: Crises

- 1968: Rainforest

- 1968 : Bypass time

- 1970: Second hand with music by John Cage

- 1970 : Items

- 1973: a day or two

- 1976: Sqare game to music Takehisa Kosugi

- 1978: David Tudor Music Exchange , Weatherings

- 1980: Duets

- 1982: Quartet

- 1983: Roaratorio to music by John Cage

- 1988 : Changing steps and five stone winds

- 1991: Beach birds

- 1993: CRWDSPCR to music by John King

- 1997 : Scenario with Rei Kawakubo costumes

- 1998: Drawn Spaces

- 1998: Pond Way with sets by Roy Lichtenstein and music by Brian Eno

- 1999: Biped

- 2000 : Interscape with sets and costumes by Robert Rauschenberg

- 2003 : Split sides

- 2005 : Views on stage

- 2006: EyeSpace

- 2007: Xover

- 2009: almost ninety

Awards

- 1982: American Dance Festival Award for

Applications

Bibliography

- John Cage, "Mers Cunningham" in Silence: Speeches and Letters (translated from American by Monique Fong), Denoel, Paris, 1970, 179 pp.

- Merce Cunningham, Dancer and dance. Interview with Jacqueline Leshev (translated from the American and annotated by Jacqueline Leshev), Belfond, Paris, 1988, 245 p. (ISBN 2-7144-1914-3)

- Raphaël de Gubernatis, Cunningham , Éditions Bernard Coutaz, Arles, 1990, 204 p. (ISBN 2-87712-005-8)

- Lorrina Niklas, "Dance", the Birth of Thought or the Cunningham Complex , National Dance Biennale in Val-de-Marne, Armand Colin, Paris, 1989, 263 pp. (ISBN 2-200-37162-4)

- David Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: Half a Century of Dance (chronicle and commentary by David Vaughan, edited by Melissa Harris, translated from English by Denise Luccioni), ed. Plume, Paris, 1997, 315 pp. (ISBN 2-84110-063-4)

- (en) David Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: Creative Elements , Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, 1997, 109 pp.

(ISBN 3-7186-5834-8)

(ISBN 3-7186-5834-8) - (en) (it) Germano Celant (dir.), Merce Cunningham , Edizioni Charta, Milano, 2000, 317 p. (ISBN 88-8158-258-9) (catalogue of an exhibition presented in Barcelona, Porto, Vienna and Turin in 1999 and 2000)

- (en) Roger Copeland, Merce Cunningham: Contemporary Dance Modernization , Routledge, New York, London, 2004, 304 pp. (ISBN 0-415-96575-6)

- (en) Caroline Brown, Case and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham , Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2009

- Merce Cunningham, camera choreographer.

Conversation with Annie Suquet and Jean Pomares , L'il d'or, Paris, 2013, 80 pp. (ISBN 978-2-913661-60-8)

Conversation with Annie Suquet and Jean Pomares , L'il d'or, Paris, 2013, 80 pp. (ISBN 978-2-913661-60-8)

Filmography

- (en) Change of Steps Directed by Elliot Kaplan and Merce Cunningham, music by John Cage, Cunningham Dance Foundation, New York, 1989, 35 min (VHS)

- (en) Three films by Merce Cunningham , directed by Elliot Kaplan and Merce Cunningham, in collaboration with John Cage and Pat Richter (music), and the voice of Robert Redford, Editions à voir, 2003 (DVD)

- (ru) Merce Cunningham Dance Company , directed by Charles Atlas, MK2 éd.

"Choreographer Merce Cunningham is dead", Liberation , 27 July 2009

"Choreographer Merce Cunningham is dead", Liberation , 27 July 2009 - ↑ (in) "Dance dreamer Merce Cunningham, dies", The New York Times , July 27, 2009

- ↑ "Choreographer Merce Cunningham is dead", Tetu , 27 July 2009

- ↑ Rosita Boisseau, "Cunningham, Proof of Three", Le Monde , December 6, 2007

- ↑ (en-US) " Cunningham " at Cunningham (accessed October 14, 2019)

- ↑ “ Cunningham”, documentary film On the outstanding choreographer ”on Komitid, (access to 1 - E January 9020) ) )

- Irina Sirotkina. Dance: the experience of understanding. Essay. Famous choreographic productions and performances. M.: Boslen, 2019.

A collection of concise essays on the nature of dance, its connection with humanitarian thought, as well as an analysis of key productions of the 20th century. - Sally Baines. Terpsichore in sneakers. Postmodern dance. Garage, 2018.

A textbook guide to the postmodern dance community of the 1960s–1980s.

Isadora Duncan's sandal, Merce Cunningham's random movements and Yvonne Ryder's anti-spectacle. A Brief History of Western Modern Dance in the 20th Century

At the end of the 19th century, the most widespread and prestigious form of dance was ballet, which was a closed institution with a rigid hierarchy and unconditional aesthetic canons. At the peak of popularity was the choreographer Marius Petipa with his extravaganza ballets (for example, the three-act Sleeping Beauty). Delsarte, a system of views and exercises of the French singer and teacher François Delsarte, created by him by the 1840s, but gained popularity in the following decades, prepared the ground for further rethinking of motor culture. Delsarte did not leave a description of his system, his students did: the method includes pantomime, work with gestures and voice intonations, and the creation of "live pictures" popular at that time. Anna Kozonina says that trauma prompted the development of Delsarte's method: having lost his voice, he associated it with incorrect physical training. At first, Delsarteism spread among actors, but gradually turned into a fashionable hobby, especially popular with American women. Among the followers of Delsarte is the famous actress Sarah Bernard, his method was inspired by Ruth Saint-Denis, an important figure in modern dance, one of the most influential schools of modern dance of the 20th century.

Anna Kozonina says that trauma prompted the development of Delsarte's method: having lost his voice, he associated it with incorrect physical training. At first, Delsarteism spread among actors, but gradually turned into a fashionable hobby, especially popular with American women. Among the followers of Delsarte is the famous actress Sarah Bernard, his method was inspired by Ruth Saint-Denis, an important figure in modern dance, one of the most influential schools of modern dance of the 20th century.

Probably, the emergence of dance experiments in the USA was provoked by the fact that America did not have its own influential ballet tradition (ballet was, in fact, imported there at the end of the 18th century). It is customary here to name Loya Fuller, an American actress and dancer who created the spectacular Serpentine dance. Lengthening her arms with bamboo sticks, she turned the folds of a voluminous tunic into like wings, which were illuminated by spotlights (the dancer herself designed colored glasses for spotlights). These visual effects, together with Fuller's free movement, which did not use ballet technique, created hypnotic images: contemporaries lost their heads over her performances and called them dances of "flowers" or "butterflies" - such dances differed significantly from the then popular showgirls numbers.

These visual effects, together with Fuller's free movement, which did not use ballet technique, created hypnotic images: contemporaries lost their heads over her performances and called them dances of "flowers" or "butterflies" - such dances differed significantly from the then popular showgirls numbers.

Fuller's visual discoveries are not forgotten today: they are unexpectedly reborn in mass culture gravitating towards the stage effect. For example, dance researcher Vita Khlopova discovers that Shakira quotes Fuller.

Shakira during the Oral Fixation Tour, 2006-2007, Splinter FilmsHowever, the real dance revolutionary who spread a new type of movement throughout Europe was, of course, the American Isadora Duncan. Nicknamed "sandal", she danced without shoes, and instead of a tutu and corset, she wore a loose tunic.

Duncan preached the rejection of learned, "fruitless" ballet movements in favor of a return to Antiquity, to the "natural" and "natural" movement. In his manifesto "Dance of the Future" of 1903 (appeared in Russia in 1908), Duncan states:

In his manifesto "Dance of the Future" of 1903 (appeared in Russia in 1908), Duncan states:

forms, but die in the same way as they happened <...> The initial, or basic, movements of the new art of dance should carry the germ from which all subsequent movements could develop, and those in turn would give birth in endless perfection to all higher and higher forms, expression of higher ideas and motives.

Duncan's views were largely influenced by Nietzsche with his idea of a dancing god ("The day you did not dance is lost," thus said Zarathustra). The worldviews of Nietzsche and Duncan converged in the concept of the new man. For the latter, his appearance was possible thanks to a dance that perfects the body and spirit, a joyful and light dance.

Students at the Isadora Duncan International Institute in New York, 1918 However, it is important to understand that Duncan never gave herself entirely to the Dionysian principle. There was almost no improvisation in her dance, she did not plunge into ecstasy on stage. Irina Sirotkina notes that every movement of the dancer was carefully rehearsed and perfected in the dance class. Interestingly, there are no records of Duncan's dance - there is only a small fragment of her performance in Paris.

Irina Sirotkina notes that every movement of the dancer was carefully rehearsed and perfected in the dance class. Interestingly, there are no records of Duncan's dance - there is only a small fragment of her performance in Paris.

Duncanism spread throughout Europe. In 1909, Duncan opened a school in France, and her followers and fans create their own studios. A similar school also appeared in Russia: in 1914, the Geptakhor free movement studio was opened in St. Petersburg. This and other Russian studios are described in detail in the textbook book by Irina Sirotkina "Free Movement and Plastic Dance in Russia". By the way, Duncan's visits to Russia and the Soviet Union resulted in a short marriage with Sergei Yesenin (1922–1925).

Duncan's craving for the ancient world correlates with the idea of the decline of civilization and the desire to search for something new, "true", characteristic of modern culture. This was also reflected in the practice of another important figure of early modern dance - Ruth Saint-Denis (we have already met her name in the list of Delsarte's followers). However, unlike Duncan, who was looking for a new movement in the past, Saint-Denis turned to the East. This appeal clearly illustrates the modernist attitude towards orientalism, the craving for everything "exotic". Edward Said describes it this way: "since Antiquity, it [the East] has been a receptacle for romance, exotic creatures, painful and enchanting memories and landscapes, amazing experiences." Saint-Denis has created productions based on various cultural traditions: ancient Egyptian (ballet Egypta), Byzantine (Dance of Theodora), Arabic (Romance of the Desert), Indian (Black and Gold Nautch, Radha), Mexican (Xochitl), biblical ( Jephtha's Daughter, Sister of Moses), Japanese (Flower Arrangement).

However, unlike Duncan, who was looking for a new movement in the past, Saint-Denis turned to the East. This appeal clearly illustrates the modernist attitude towards orientalism, the craving for everything "exotic". Edward Said describes it this way: "since Antiquity, it [the East] has been a receptacle for romance, exotic creatures, painful and enchanting memories and landscapes, amazing experiences." Saint-Denis has created productions based on various cultural traditions: ancient Egyptian (ballet Egypta), Byzantine (Dance of Theodora), Arabic (Romance of the Desert), Indian (Black and Gold Nautch, Radha), Mexican (Xochitl), biblical ( Jephtha's Daughter, Sister of Moses), Japanese (Flower Arrangement).

With the founding of the Denishawn School of Dance with her husband Ted Shaw in 1915, where, in addition to the classics, Oriental techniques and the Delsarte system were taught, St. Denis significantly influenced the next generation of dancers.

One of the outstanding students of the Denishawn school is Martha Graham, a key figure in modern dance (together with Doris Humphrey, Chania Holly and Charles Weidman, Graham is one of the four "founding fathers" of modern).

Rethinking and pushing back both European ballet and the cabaret/vaudeville genre popular in the US, Graham argued that dance should reflect on big issues. She often worked with biblical and ancient subjects (focusing, by the way, more often on the images of heroines and the figure of a woman, and thus resonating with feminist thought).

Graham developed her own technique for training dancers based on the principles of breathing - contraction and release. The technique is preserved and taught to this day at the Martha Graham Dance Company.

One of Graham's key productions is Lament (1930).

Martha Graham, "Lament", 1935This is how Vita Khlopov describes "Lament":

"Martha Graham is sitting on a bench, wrapped in a cloth like a cocoon.

This cocoon, from which it is impossible to break free, personifies the pain and suffering forever attached to humanity. The production is certainly innovative: Graham not only removed the actual dance from the dance (she never gets up), but also limited the movement with a tight costume, as if hiding it inside.

This expressive image, like Fuller's wings, has been copied and played up in pop culture:

Madonna for Harper's Bazaar magazine, 1994, photographs by Peter LindberghJessica Love, 2007 Ausdruckstanz. For example, Mary Wigman believed that dance is able to reflect not only on the sublime and refined, but also on the heavy and painful, and a dancing woman can transmit not only an image of lightness and beauty, but also plastically comprehend anger, suffering, sorrow. These ideas are realized in her famous “Dance of the Witch”, where Wigman, using a mask, makes sharp, chaotic movements, creating an unstable and frightening image. It is noticeable how much such a dance differs from Duncan's ideology, which is in 1910s at the pinnacle of his glory. Mary Wigman, "Dance of the Witch", 1926

Mary Wigman, "Dance of the Witch", 1926 Later, the tradition of German expressive dance developed in the famous dance theater of Pina Bausch (it was finally formed by the end of the 1970s). The essence of Pina's method is well articulated in one of her most famous statements:

“The last thing I'm interested in is how people move. I'm interested in what drives them."

For dance theater, the concept of expressive movement (not necessarily technically perfect) is important, conveying the inner state of the dancer. For example, in one of Bausch's most famous performances, Cafe Müller, the actors scurry around the stage, now and then bumping into chairs and other pieces of furniture.

In 2011, two years after Pina's death, Wim Wenders released a documentary about her.

Pina Bausch in her play Café Müller, 1978While German expressive dance flourished in Europe, American choreographers focused on overcoming modern dance and experimentation.

In 1938, a new dancer, Merce Cunningham, joined Martha Graham's troupe. Subsequently, he would become one of the most radical critics of modern dance. The latter was accused of having, in demonstrating his opposition to classical dance, created, in fact, its copy with a strict training system, recognized authorities, a penchant for spectacle and theatricality. After leaving the Graham Company, Cunningham began to develop his own method based on chance: the choreography was plotless and not related to music, often the order of the dance combinations was determined before the start of the performance using a roll of dice, and the dancers could hear the music on stage for the first time. Later, Cunningham even used a computer program that created new bizarre movements, where different parts of the body moved independently of each other. The choreographer collaborated a lot with another experimenter, but already in the field of music, John Cage, known to the general public for his minimalist piece “4’33”, consisting of 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence. By the way, Cunningham and Cage were partners in life as well.

By the way, Cunningham and Cage were partners in life as well.

Cunningham's big fan is Mikhail Baryshnikov, a living legend of classical and contemporary dance. Here's how he previews his Cunningham-dedicated photo exhibition MERCE MY WAY (it was brought to Russia in 2008-2009):

“Merce's work fits perfectly into the photographic image. He uses space, its volume, better than any of the choreographers in the world. He uses dancers as the perfect instruments to express his vision. He gives them the most intricate and beautiful movements, bending their torsos in an unpredictable, sometimes unimaginable way. Watching Cunningham's numbers through a camera lens is a lesson in the limits and limitations of the dancer's body."

At the end of 2019, a documentary film of the same name by Alla Kovgan was released about Cunningham.

Merce Cunningham and his company perform the TV Rerun program in New York, 1975, photo: JACK MITCHELL / GETTY IMAGES Cunningham is considered to be a choreographer balancing between modern dance and the next era of dance, postmodern. Anna Kozonina connects the appearance of the latter with the "crisis of spectacle in the art of dance".

Anna Kozonina connects the appearance of the latter with the "crisis of spectacle in the art of dance".

The choreographers continued the tradition set by Cunningham of denying spectacle, but moved even further - to research and search for new meanings in primitive movements, such as walking, running, simple jumps.

Yvonne Reiner, a prominent figure in postmodern dance, published the famous “No Manifesto” in 1964, which incorporates the key ideas of the time:

that existed from 1962 to 1964 - a very short time, which was enough to unite the strongest team of dance revolutionaries. Judson Church Theater got its name from the place of one of the first shows - Judson Church. The development of "non-theatrical" spaces: streets, parking lots, galleries and parks is a characteristic feature of postmodern dance. In addition, choreographers began to involve not only professional dancers in the productions, but also ordinary people, demonstrating a variety of bodies and ways of movement.

The peak of postmodern dance is minimalism and the so-called "analytical dance", a craving for theorizing and reinventing motor language. Anna Kozonina emphasizes that postmodern dancers broke with several traditions of the past at once: they got rid of both the literary narrative characteristic of Martha Graham and the specific technique of Merce Cunningham. Judson Church Theater significantly influenced the further development of dance. Among its participants is Steve Paxton, who later created contact improvisation (One of the forms of modern dance in which two or more partners interact through a point of contact, working with each other's inertia, effort and weight. The first performance of Magnesium contact improvisation took place at 1972 in Oberlin (USA), Deborah Hay, Trisha Brown, David Gordon and others. Yvonne Reiner, We Shall Run, 1965, photo Peter Moore

The peak of postmodern dance is minimalism and the so-called "analytical dance", a craving for theorizing and reinventing motor language. Anna Kozonina emphasizes that postmodern dancers broke with several traditions of the past at once: they got rid of both the literary narrative characteristic of Martha Graham and the specific technique of Merce Cunningham. Judson Church Theater significantly influenced the further development of dance. Among its participants is Steve Paxton, who later created contact improvisation (One of the forms of modern dance in which two or more partners interact through a point of contact, working with each other's inertia, effort and weight. The first performance of Magnesium contact improvisation took place at 1972 in Oberlin (USA), Deborah Hay, Trisha Brown, David Gordon and others. Yvonne Reiner, We Shall Run, 1965, photo Peter Moore By the 1990s dance had come into active collaboration with other contexts, such as contemporary art.

It also opened up to new plastic forms — the scenes of academic theaters are captured by street dance, knowledge of anatomy is considered good form among dancers, they increasingly work with the voice and interact with the theatrical tradition.

It is often said that the movement has become politicized. In any case, hardly anyone would call today's dance an exclusively visual art, a set of "beautiful" movements. The contribution to a serious and attentive attitude to dance was formed throughout the 20th century.

The Russian stage does not lag behind experiments and discoveries in the field of modern dance.