How to teach dance technique

5 Technique & Movement Skills To Teach Your Dance Students

About a year ago (maybe more – time flies!), someone in a dance teachers’ group on Facebook posed an interesting question:

What are the 5 skills that you think are most important for your students to learn?

This was a particularly vexing topic for me, because I had a hard time even deciding what counts as a “skill,” anyway. Quality dance training impacts every part of a students’ life: the physical, of course, but also the social, emotional, creative, cognitive, and even spiritual. To narrow down just 5 things I want my students take away from such a massive range of potential lessons was tricky at best.

But the question has stuck with me, and I think it’s a good one to explore here on the blog. To do so in a more manageable way, I’m going to separate my answers out over a few posts, each looking at a different kind of skill. This post is about the top 5 movement or technique skills I try to instill in my students. (Check out my lists of social-emotional and artistic skills for students to learn through dance!)

Throughout my career I’ve studied and taught in a wide range of settings: studios, colleges, K-12 schools, conservatories, and community programs. I’ve worked with students from age 2-60, some of whom where stepping foot into the studio for the first time in their entire lives, and some of who had been dancing even longer than I have. I’ve led classes for dancers in the midst of their careers, trained students with professional aspirations, and taught novice students who love dance and those who were forced to be in class because of their school curriculum.

My training and teaching experience is limited to ballet, modern dance, contemporary, improvisation, jazz (a mix of authentic and concert styles), and creative dance. I have a great appreciation for tap, Hip Hop, and global movement practices, and I’m always looking to diversify and decolonize my teaching practices. However, my perspective is largely informed by my experience in Western concert dance styles.

I list my background here because, in all of the different teaching experiences I’ve had, the essential movement skills I value are the same. I believe that there are foundational elements of movement practice that are valuable for all students to master, regardless of their learning environment, age or skill level, or the genre of dance being studied.

I believe that the standardization of “good technique” is overrated. Technique itself varies greatly depending on the dance genre being practiced. Within those different genres, each students’ technique will and should be a little different based on how their bodies are able to understand and fulfill the expectations of the form. Teaching technique in a one size fits all way is detrimental to students. It is our job as educators to help them find their own technique within the form.

That being said, this list contains 5 fundament movement skills that I think help students find their own good technique within the genres being studied. Each skill will be be presented and explained in different ways depending on the dance genre, and my expectations for their understanding, embodiment, and application of the skills will differ based on their age, genre, level, body and maturity. Overall, however, I believe that most good movement skills are applicable across a wide range of dance styles. When students master these essential skills, they better understand their bodies and how to adapt to the expectations of different dance genres and choreographers. So, without further ado, I humbly present the top 5 technique and movement skills you should be teaching your students.

Each skill will be be presented and explained in different ways depending on the dance genre, and my expectations for their understanding, embodiment, and application of the skills will differ based on their age, genre, level, body and maturity. Overall, however, I believe that most good movement skills are applicable across a wide range of dance styles. When students master these essential skills, they better understand their bodies and how to adapt to the expectations of different dance genres and choreographers. So, without further ado, I humbly present the top 5 technique and movement skills you should be teaching your students.

1.) Functional Alignment: To put it most simply, all dancers should be working toward an understanding of how their muscles, bones, and joints work together to properly align the body when standing still AND when moving through space on the low, mid, and high levels. Students who have this understanding can move safely (without excessive risk for injury) and efficiently (without excess strain, tension, exertion, or awkwardness), and transition more easily among dance styles, choreographers’ expectations, and the demands of different teachers.

Students who have this understanding can move safely (without excessive risk for injury) and efficiently (without excess strain, tension, exertion, or awkwardness), and transition more easily among dance styles, choreographers’ expectations, and the demands of different teachers.

- The Challenge: Based on body type, flexibility, strength, joint mobility, prior injury, and a host of different issues, “proper” functional alignment necessarily won’t be the same for everyone. The key is to help students discover their individual best alignment practices an how to maintain and change them as needed while moving. This takes time, practice, and patience – for you and the student!

- My Advice: For beginning students, you need to keep it simple! That was something I didn’t realize until I read Jan Ekert’s beautiful book, Harnessing the Wind: The Art of Teaching Modern Dance. If you walk into a beginning class and start drilling the nuances of engaging the deep rotators to maintain turnout, you will very likely not only confuse the daylights out of most the students, but also steal some of the joy of dancing from them! That doesn’t mean you need to ignore proper alignment completely with beginning or young dancers.

There are lots of playful creative movement games that help develop body awareness, and fun metaphors can help get complex ideas across in a simplified way. Here are some of my ideas for a playful approach to ballet for young dancers. As dancers progress, build upon their existing body awareness and knowledge by incorporating somatic practices, such as Bartenieff Fundamentals, Alexander Technique, or even Pilates. Be sure to ask dancers to explain HOW new alignment ideas feel in their own bodies, encourage them to ask questions, and see that they can articulate and demonstrate how these somatic practices translate to their dance practice. For more ideas, see my series on empowering students in the ballet studio.

There are lots of playful creative movement games that help develop body awareness, and fun metaphors can help get complex ideas across in a simplified way. Here are some of my ideas for a playful approach to ballet for young dancers. As dancers progress, build upon their existing body awareness and knowledge by incorporating somatic practices, such as Bartenieff Fundamentals, Alexander Technique, or even Pilates. Be sure to ask dancers to explain HOW new alignment ideas feel in their own bodies, encourage them to ask questions, and see that they can articulate and demonstrate how these somatic practices translate to their dance practice. For more ideas, see my series on empowering students in the ballet studio.

2.) Fluidity and Stability of the Spine: So much of dance technique and choreography, in almost every genre, involves articulation and manipulate of the spine – be it subtle as in the ballet epaultment or powerful as in jazz isolations and West African polyrhythms. What separates a good dancer from a great one, for me, is often how the dancers find the balance between fluidity and stability in their spine. Can they execute a classic modern dance spiral, luscious ballet epaulment, a stellar contraction and hinge, well-defined rib cage isolations, and sinewy complex contemporary choreography? (And those are just concepts from Western dance forms…) At the same time, can they find their own neutral spine on the floor, sitting, and standing, and maintain it throughout a leggy adagio or tricky weight shift progression?

What separates a good dancer from a great one, for me, is often how the dancers find the balance between fluidity and stability in their spine. Can they execute a classic modern dance spiral, luscious ballet epaulment, a stellar contraction and hinge, well-defined rib cage isolations, and sinewy complex contemporary choreography? (And those are just concepts from Western dance forms…) At the same time, can they find their own neutral spine on the floor, sitting, and standing, and maintain it throughout a leggy adagio or tricky weight shift progression?

- The Challenge: So much of the way we think about our spines is integrated with hold we think about “holding” or “using” our core muscles. Often we use metaphors for engaging the core that lead to either a tipped or tilted pelvis (therefore whacking the spine out of neutral), or subconsciously encourage dancers to limit their spinal mobility in the name of a “strong” core. How do we find the balance between encouraging our dancers to develop proper core support while also developing more mobility in the spine?

- My Advice: My dancing completely changed the day I was given permission NOT to think about “using” my core.

Suddenly, I was relying on skeletal alignment for support, not brute muscular engagement, and I found a new freedom of movement, particularly in my spine. Granted, I had been dancing for over 20 years and was in graduate school, so I had a degree of body maturity that enabled me to work in this way without completely “letting go” of all muscular engagement. However, I have tried to use more skeletal cuing with my dancers since that time. “Lengthen your spine,” “release your tailbone,” and “float your ears above your shoulders” can all work well to help intermediate and advanced students find skeletal support for their dancing, which leads to natural muscular engagement. Check out excerpts of my favorite spine warm-up here.

Suddenly, I was relying on skeletal alignment for support, not brute muscular engagement, and I found a new freedom of movement, particularly in my spine. Granted, I had been dancing for over 20 years and was in graduate school, so I had a degree of body maturity that enabled me to work in this way without completely “letting go” of all muscular engagement. However, I have tried to use more skeletal cuing with my dancers since that time. “Lengthen your spine,” “release your tailbone,” and “float your ears above your shoulders” can all work well to help intermediate and advanced students find skeletal support for their dancing, which leads to natural muscular engagement. Check out excerpts of my favorite spine warm-up here.

3.) Use of Weight: If I had to name the two most important “steps” I teach, they would be undercurve and overcurve. These are basically the modern-dance terms for concepts that are utilized many dance forms; ballet dancers and jazzerinas might know them better as chasse and pique. More than anything else, I believe these concepts, help dancers understand the relationship of their body to gravity, allowing them to find groundedness and ballon. Dancers who can drop their weight and connect with the floor in a good undercurve have stronger plie-releves, higher jumps, smoother transitions between movements, and are generally better able to adapt to movement that goes into and out of the floor. Dancers who can shift their weight and transfer their hips over their foot and ankle in an overcurve find more suspension in their movement, can transfer between balance and off-balance movement, and perform most traveling turns (like pique turns) with greater ease. Undercurves and overcurves are truly powerhouse ideas to explore in class if you want your dancers to have a more dynamic use of weight!

More than anything else, I believe these concepts, help dancers understand the relationship of their body to gravity, allowing them to find groundedness and ballon. Dancers who can drop their weight and connect with the floor in a good undercurve have stronger plie-releves, higher jumps, smoother transitions between movements, and are generally better able to adapt to movement that goes into and out of the floor. Dancers who can shift their weight and transfer their hips over their foot and ankle in an overcurve find more suspension in their movement, can transfer between balance and off-balance movement, and perform most traveling turns (like pique turns) with greater ease. Undercurves and overcurves are truly powerhouse ideas to explore in class if you want your dancers to have a more dynamic use of weight!

- The Challenge: Like many good things in dance (as in life), nailing a proper undercurve or overcurve takes time, repetition, and focus. They can also be very, very boring.

How can you keep it fresh for your dancers as they struggle to really find the proper shift of weight with the pelvis, while maintaining good alignment?

How can you keep it fresh for your dancers as they struggle to really find the proper shift of weight with the pelvis, while maintaining good alignment? - My Advice: Don’t spend too much time on the actual movements themselves, but instead highlight just how prevalent these basic ideas are in just about every aspect of dance technique. I do include an undercurve and overcurve combination in almost every modern, contemporary, and lyrical class that I teach, and in ballet and jazz I include plenty of weight shifts like chasse, temps levee, pique, ball change, and sliding movements. But, I also point out where else they show up in class: in triplets or balances, in jumping combinations, any time you chasse into a releve, when stepping up into a balance, in turn preps, etc. I do this verbally, of course, but it’s often more powerful to SHOW it through my personal demonstration, and to have students observe others in class who have “gotten it.” Undercurve and overcurve also make great concepts for improv games.

For example: Travel across the floor with a partner, but you always have to be doing the opposite of your partner (so if your partner undercurves, you overcurve).

For example: Travel across the floor with a partner, but you always have to be doing the opposite of your partner (so if your partner undercurves, you overcurve).

4.) Articulation of the Feet and Ankles: Can you point, flex, pronate, supinate, find a neutral foot, lift just the toes, lift just the heel, and slide your foot across the floor without socks? Being able to articulate your feet and ankles is not only important as a dancer, it’s also important as a human being. (I’ll let Katy Bowman tell you more…) So often I see dancers who hold excess tension in their feet and ankles, which impacts balance, releve, jumping, weight shift, turning, traveling movement of all kinds, and more. Being able to find a full range of foot articulation (beyond point and flex) is incredibly important for dancers of every genre.

- The Challenge: There is just SO. LITTLE. TIME. in class. Are you now telling me I need to include foot articulation exercises too?

- My Advice: No need to break out the therabands in every class.

While dedicated time for foot stretch and strengthening exercises is lovely and important especially for pre-pointe and pointe students, I have found making better use of the exercises I am already including in class can had a big impact. For example, have your ballet students do tendu and degagge combinations from 6th position (parallel) so that they can really feel the articulation from the whole foot pressing into the ground, to the ball of the foot, to the whole point, then reverse. Include “toe push-ups” or “toe rond de jambes in a tendu combination (Toe Push-up: my silly name for releasing the ball of the foot into the ground so you are standing “on the walk,” then pressing back into to the full point. Toe rond de jambe is the same thing with a circle instead of just a push-up). Have your students deliberately overpronate and oversupinate in a coupe combination not only so that they develop mobility in those directions, but also practice finding finding the correct position.

While dedicated time for foot stretch and strengthening exercises is lovely and important especially for pre-pointe and pointe students, I have found making better use of the exercises I am already including in class can had a big impact. For example, have your ballet students do tendu and degagge combinations from 6th position (parallel) so that they can really feel the articulation from the whole foot pressing into the ground, to the ball of the foot, to the whole point, then reverse. Include “toe push-ups” or “toe rond de jambes in a tendu combination (Toe Push-up: my silly name for releasing the ball of the foot into the ground so you are standing “on the walk,” then pressing back into to the full point. Toe rond de jambe is the same thing with a circle instead of just a push-up). Have your students deliberately overpronate and oversupinate in a coupe combination not only so that they develop mobility in those directions, but also practice finding finding the correct position. Include ankle circles in a pique combination or while traveling the leg up to retire and back down. Have students in all genres (yes, even ballet) dance barefoot to really feel the foot on the floor from time to time.

Include ankle circles in a pique combination or while traveling the leg up to retire and back down. Have students in all genres (yes, even ballet) dance barefoot to really feel the foot on the floor from time to time.

5.) General Coordination: I saved the most important for last, in my opinion. So often students can have good technique – nice execution of steps, decent alignment, etc. – but still be lacking that je ne said quoi. In my opinion, that “special something” is often good overall body coordination. I think of body coordination in terms of Laban/Bartenieff Fundamentals, which are also articulated in Anne Green Gilbert’s Brain Dance:

- Breath – Coordinating the movement of the body with the breath

- Sensation – Responding to touch and feeling

- Core-Distal – Connection from center of body out to the extremities and back

- Head-Tail – Connection through the spine

- Upper Body/Lower Body – Being able to isolate, connect, and coordinate the movement of these two halves of the body

- Body-Half (Homolateral Movement) – Being able to isolate, connect, and coordinate the movement of the right side and left side of the body

- Cross-Body (Contralateral Movement) – Being able to cross the midline and coordinate movement from one side through the center of the body to the other side

- Vestibular – Being able to move on and off-balance

A dancer who can demonstrate a deep understanding and embodiment of these principles is often, to me, the most beautiful mover in the room. This level of coordination allows for a deep body awareness that permeates every aspect of dancing and allows for more mature, nuanced, and full movement through space.

This level of coordination allows for a deep body awareness that permeates every aspect of dancing and allows for more mature, nuanced, and full movement through space.

- The Challenge: Students (and often times parents) don’t think of coordination as a skill, especially not a “dance skill.” They don’t realize the coordination can improve with time and practice, or that it provides the foundation for truly great dance technique. In their minds, you are either coordinated or not. They want class time to be spent working on “dancing” and not coordination work.

- My Advice: Sneak it in if you have to, baby. In a perfect world, students and parents would trust our judgement, or at least be moved by our testimonies as to the benefits of the work we do in class. But in this imperfect and sometimes cruel world, sometimes you need to mix the medicine in with the ice cream and trust that the benefits outweigh the sugar and calories. Coordination exercises can be “disguised” in barre work, floor stretching, somatic warm-ups, improv exercises, and more.

Stay tuned for a future post with more on this …. but for now, learn more about the Brain Dance and find ways to incorporate these ideas into your own classes.

Stay tuned for a future post with more on this …. but for now, learn more about the Brain Dance and find ways to incorporate these ideas into your own classes.

Check out the other posts in this series to discover the social-emotional and artistic skills that I try to instill in my students!

Visit my Resources page for tools to support a holistic teaching practices, sign up for my quarterly newsletter, or join me on Facebook at The Holistic Dance Teacher.

Teaching Dance Technique

I believe a club caller should teach dance technique. Probably many club callers will take exception to this. “I'm a caller, not a teacher”, they may say. But if the club callers don't do the job, who will? People occasionally ask me where they can go to learn to dance, and I don't have a good answer. There are plenty of clubs where you can learn dances (though we tend not to, relying on the caller), but very few places where you can learn how to dance well. There's an occasional Technique session at a festival or dance weekend. I sometimes teach a bit of technique at a Saturday Dance (in desperation), but I don't think that's the best place for it. The club callers are the ones on the spot, who know their club's strengths and weaknesses and could do a little teaching week by week to bring the whole standard up. I'm not for a moment suggesting that you should spend vast amounts of time teaching the finer points every week — that may well drive people away — but ten minutes a week could have a dramatic effect on the way your club dances.

There's an occasional Technique session at a festival or dance weekend. I sometimes teach a bit of technique at a Saturday Dance (in desperation), but I don't think that's the best place for it. The club callers are the ones on the spot, who know their club's strengths and weaknesses and could do a little teaching week by week to bring the whole standard up. I'm not for a moment suggesting that you should spend vast amounts of time teaching the finer points every week — that may well drive people away — but ten minutes a week could have a dramatic effect on the way your club dances.

Another excuse is “I don't know how to teach technique”. Well, nor did I when I started calling, but I saw how other people did it, thought hard about it, wrote myself some notes and had a go. I don't consider myself a particularly stylish dancer, but I could see there was a need for this sort of teaching. I remember telling Betty Chater that I sometimes wonder what right I have to stand up in front of a group of people and tell them how they should be dancing, and I was greatly reassured when she immediately said “Oh, so do I”!

I'm afraid another excuse is “I'm not a good enough dancer to teach technique”. This leads to the immediate question: “Why are you a caller then?” Surely anyone teaching any subject should be able to do what they're teaching! But probably the most common answer is “People don't come here to be taught — they'll pick it up as they go along”. And the results of that approach are plain to see in the lamentably low standard of English Folk Dancing in this country. People are as likely to pick up the wrong way of doing things as the right way, if that's what they see. Isn't it about time we changed our approach? All over the country I hear people complaining that we need new members or the clubs will die out, but nobody seems to be doing much about it. If newcomers visit your club, are they impressed by what they see and therefore willing to put in a bit of effort to join in with the activity? Or do they see a bunch of people ambling about with no style or life to them? If we want to encourage new dancers — particularly younger ones — we must present them with something vital, something which catches their enthusiasm and interest.

This leads to the immediate question: “Why are you a caller then?” Surely anyone teaching any subject should be able to do what they're teaching! But probably the most common answer is “People don't come here to be taught — they'll pick it up as they go along”. And the results of that approach are plain to see in the lamentably low standard of English Folk Dancing in this country. People are as likely to pick up the wrong way of doing things as the right way, if that's what they see. Isn't it about time we changed our approach? All over the country I hear people complaining that we need new members or the clubs will die out, but nobody seems to be doing much about it. If newcomers visit your club, are they impressed by what they see and therefore willing to put in a bit of effort to join in with the activity? Or do they see a bunch of people ambling about with no style or life to them? If we want to encourage new dancers — particularly younger ones — we must present them with something vital, something which catches their enthusiasm and interest. I don't share the belief that people will walk out in disgust if the caller spends five or ten minutes an evening teaching them how to do some move or step better. “Little and often” is much better than putting on a Dance Technique Workshop once every couple of years — which the people who most need it wouldn't dream of going to. Why not give it a try for three months and see what happens?

I don't share the belief that people will walk out in disgust if the caller spends five or ten minutes an evening teaching them how to do some move or step better. “Little and often” is much better than putting on a Dance Technique Workshop once every couple of years — which the people who most need it wouldn't dream of going to. Why not give it a try for three months and see what happens?

How do you teach Dance Technique? First of all, what is Dance Technique? It's a set of skills which enable you to dance well: possibly to impress an audience or adjudicator if you're in a Display Team, but usually to increase the enjoyment of yourself, your partner and the rest of the set. Technique is not artificiality — English Folk Dancing is supposed to look natural and unforced — but it still requires a lot of skill.

Some aspect of technique are: moving in time with the music; fitting the steps to the music so that you arrive in the right place at the right time; dancing in an appropriate style for the dance and circumstances; being aware of the other dancers and helping them as necessary. But how do you teach this?

But how do you teach this?

First of all, you have to take people as you find them. This is where you as a Club Caller have the advantage over me brought in from outside to run a technique workshop. You know what your dancers can do, what they will find difficult, what they will object to, and how far you can push them. In his wonderful book “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People”, Steven Covey distinguishes between managers and leaders. People follow a manager through fear of the consequences — he may make them redundant, or not give them a rise, or just make their working lives miserable. But people follow a leader because they want to — they are inspired by her, they believe in her, they enjoy the way she runs things. Obviously a caller falls into the leader category: he rules by consent, and if he goes too far the dancers will sit down or walk out — or at least not turn up the next time he's booked to call.

As I said earlier, the trick is to do things gradually, rather than hitting them with half an hour's technique in one go. And you need to get the dancers on your side. If your attitude comes across as “You lot are terrible dancers and I'm going to sort you out”, you've had it before you start. That's a manager speaking. A leader would say something like: “This kind of dancing is great fun, and we all do it because we enjoy it, so let's spend a few minutes looking at ways to make it more enjoyable for everybody”. Remember, if you're not enthusiastic as a caller, the dancers aren't likely to be either. If you find the “Seven Habits” hard going, why not try Dale Carnegie's highly readable “How to win friends and influence people”? It will give you lots of ideas about dealing with people and making them willing to do what you want — and the reason the title has become a cliché is that it's such a great book.

And you need to get the dancers on your side. If your attitude comes across as “You lot are terrible dancers and I'm going to sort you out”, you've had it before you start. That's a manager speaking. A leader would say something like: “This kind of dancing is great fun, and we all do it because we enjoy it, so let's spend a few minutes looking at ways to make it more enjoyable for everybody”. Remember, if you're not enthusiastic as a caller, the dancers aren't likely to be either. If you find the “Seven Habits” hard going, why not try Dale Carnegie's highly readable “How to win friends and influence people”? It will give you lots of ideas about dealing with people and making them willing to do what you want — and the reason the title has become a cliché is that it's such a great book.

So, having sorted out your approach to the dancers, how do you teach them technique? There are many ways. Betty Chater never said “Now I'm going to teach you all how to dance better”, but during a workshop or dance she would impart quite a lot of technique, without getting anyone's back up. She would gently suggest that if you tried it this way you might enjoy the dance more. She also taught by example; whenever you watched her dance you could see the style shining through.

She would gently suggest that if you tried it this way you might enjoy the dance more. She also taught by example; whenever you watched her dance you could see the style shining through.

Let's take something really simple: lines forward and back. It should take three steps and a close for each part. What you often get is two steps forward and a sort of close, two steps back and a sort of close, then either wait two beats for the music to catch up or carry on with the next movement. How can you get the dancers to do it right? Well, they may never have thought about it before. It's such a simple movement; how could they possibly be doing it wrong? Point out that it's the same movement as “Up a double and back”. The difference is that instead of all moving in the same direction they're meeting someone, so they need to take smaller steps rather than fewer. Demonstrate it to them while singing the music; some people learn best by seeing. Some people advocate counting it out — “forward, two, three, together; back, two, three, together” — others say this encourages people to count rather than listen to the music. You can make a joke of it; I've had a whole room of dancers shouting out “one, two, three, together”, but at least they were doing it right. As I keep saying, don't hammer them into the ground with it. They'll get bored if you keep on the same point for too long. But it's a good idea to return to it a couple of times in the evening. The next time the movement turns up, you can say (with a smile): “We all know how to do this, don't we”.

You can make a joke of it; I've had a whole room of dancers shouting out “one, two, three, together”, but at least they were doing it right. As I keep saying, don't hammer them into the ground with it. They'll get bored if you keep on the same point for too long. But it's a good idea to return to it a couple of times in the evening. The next time the movement turns up, you can say (with a smile): “We all know how to do this, don't we”.

Let's look at a more complicated movement — a Grimstock (mirror) hey. I remember once asking the dancers at a workshop why they weren't fitting it to the music, and getting the reply “no-one's ever told us how”. Of course, before they can think about fitting it to the music they need to be able to follow the track. Don't be afraid to spend the time necessary to teach a movement properly; it wastes more time in the long run if you don't. Start with the ones facing down and the threes facing up, both with inside hands joined, and the twos facing up slightly apart. Emphasise that you take your partner's hand at the ends and let go in the middle: “bulge in the middle” may get a laugh and therefore be remembered better. You may need to tell the threes not to let the ones get through them. Now set them going, and keep saying “Take your partner's hand at the end; let go in the middle”. Remember to “praise the slightest improvement and praise every improvement” (Dale Carnegie). I once heard of a well-known dance teacher: “She always criticises us; she never tells us we've done anything well”. On the other hand, sometimes you can “throw down a challenge” (Carnegie again). If you've got the crowd on your side you can get away with saying “That was terrible! I know you can do it better than that”. But don't use this approach too often!

Emphasise that you take your partner's hand at the ends and let go in the middle: “bulge in the middle” may get a laugh and therefore be remembered better. You may need to tell the threes not to let the ones get through them. Now set them going, and keep saying “Take your partner's hand at the end; let go in the middle”. Remember to “praise the slightest improvement and praise every improvement” (Dale Carnegie). I once heard of a well-known dance teacher: “She always criticises us; she never tells us we've done anything well”. On the other hand, sometimes you can “throw down a challenge” (Carnegie again). If you've got the crowd on your side you can get away with saying “That was terrible! I know you can do it better than that”. But don't use this approach too often!

Once they're confident of the track you can look at the timing — though if they've struggled with the track it's probably best to do an easier dance next, and teach another dance involving a Grimstock hey later in the session. You can walk the track on your own, either singing the tune, or to the music, or maybe just counting. The dancers need to be aware that after four bars of music (eight steps) they should be in half-way positions. Now get them to try it to the music, and tell them each time: “You should be half-way now”; “You should be home now”. Many dancers seem to think it's good policy to keep a few steps ahead of the music; you need to let them know that being ahead is just as bad as being behind.

You can walk the track on your own, either singing the tune, or to the music, or maybe just counting. The dancers need to be aware that after four bars of music (eight steps) they should be in half-way positions. Now get them to try it to the music, and tell them each time: “You should be half-way now”; “You should be home now”. Many dancers seem to think it's good policy to keep a few steps ahead of the music; you need to let them know that being ahead is just as bad as being behind.

One more example. I was teaching a “Hole in the Wall” cross at the Intermediates Class at Cecil Sharp House and trying to emphasise that it's three steps to cross and face, three steps to fall back to each other's place, but they were having real problems with it; they wanted to cross and face in two steps and step back on the third. Suddenly inspiration struck. “You need to hover on the third beat”, I told them, and instead of “Cross, two, three, back, two three” I said “Cross, two, hover, back, two three”. The whole movement came together once they saw what I was getting at — and they were pleased with themselves.

The whole movement came together once they saw what I was getting at — and they were pleased with themselves.

I realise that I've talked at length on just one aspect of teaching technique — fitting the movements to the music — but I felt you needed some real detail rather than vague exhortations to get your club dancing better. Of course there's a lot more to it.

I called at a Club Night in Luton in May 2001 — never been there before — and I decided in advance that I would teach the waltz step. I've got a page of notes I've written on Waltz Time, so I went through that and we did a simple dance in waltz time. In the second half I called “An Enchanted Place” — a more complicated waltz dance — and reminded them of what I'd said about the step. I didn't hear any complaints — any murmurs of “I came here to enjoy myself, not to be taught”. I mentioned a few other technique points during the evening — not a separate teaching session, just something while I was doing the walkthrough or the dance. Barbara Burton, who was playing for me, said they were dancing much better by the end of the evening. And lots of them came up to me afterwards and said how much they'd enjoyed the evening, which they certainly wouldn't have done if they'd objected to being taught. On the other hand I've never been booked there again.

Barbara Burton, who was playing for me, said they were dancing much better by the end of the evening. And lots of them came up to me afterwards and said how much they'd enjoyed the evening, which they certainly wouldn't have done if they'd objected to being taught. On the other hand I've never been booked there again.

General points about teaching technique

You must know what you want them to do, and what you don't want. If you just have a vague idea of “I'd like them to dance better”, it won't happen. Of course you can be spontaneous too (though this only comes with experience) — you can see them doing something wrong and seize the opportunity to correct it. Some people say you should never show them something wrong, but I find it very helpful when the teacher says “I don't want it like this; I want it like this”. Of course you need the confidence to get down there and show it, rather than staying safely on the stage.

You have to know most of the answers, but not all of them. There have been times when I've taught something and someone says “But surely it's better to do it like this”. If they're right, or if both ways have their merits, don't be afraid to admit it. People shouldn't lose confidence in you because you're willing to see other people's points of view rather than dogmatically insisting that your way is right. Don't feel threatened if people question you — it means they're interested and they feel secure enough to ask you things. Don't dismiss their ideas as nonsense — that gets you a bad reputation. If you can say something like “Well, you can do it that way, but I think you'd have a problem in this situation”, they are more likely to come round. You can demonstrate both ways and ask the other people what they think — it doesn't have to be all you. And if most of them agree with you, you've made your point without putting the other person down. I've certainly changed my views as a result of what other people have said at my Technique Workshops — it doesn't do to be too dogmatic. You can always finish the topic by saying “Well, I still prefer my way, but other people will tell you differently”. Remember that in English and American Folk Dancing there is no one right way (as there is in RSCDS Scottish or Modern Western Square).

You can always finish the topic by saying “Well, I still prefer my way, but other people will tell you differently”. Remember that in English and American Folk Dancing there is no one right way (as there is in RSCDS Scottish or Modern Western Square).

I've written myself sets of notes on various aspects of Dance Technique, all of which are available here. When I'm asked to do a Technique Workshop, or indeed when I'm doing any Workshop or perhaps a Club Night, I can look through my notes and select a few topics. I also have the names of a few dances which illustrate the topics. So I can put together a session fairly easily — except when I decide it's time I did something new! Sometimes, especially if I've just written a new set of notes, I will basically read them out — though I hope it doesn't come across that way. Sometimes I look through the notes just before I'm about to speak again, and enough of it stays in my memory to enable me to seem spontaneous. It's important that you sound lively and enthusiastic, or they certainly won't be. If you're really not interested in technique, don't teach it. You need to come across as confident without being dogmatic — just as you do when calling a dance. Remember, you can't force them to do it your way; you can only persuade them.

If you're really not interested in technique, don't teach it. You need to come across as confident without being dogmatic — just as you do when calling a dance. Remember, you can't force them to do it your way; you can only persuade them.

Dance Style

We all know stylish dancers — and we all know lots more who aren't. How do you teach style?

First of all, there's no one style — Playford, American and English Tradition all have their own style, and what looks right in one is very wrong in another. Let's look at the Playford style as it is danced in England in the 21st century — other countries and other centuries are certainly different. Cecil Sharp quoted “a lady of distinction” as saying: “The characteristics of an English Country Dance is that of gay simplicity. The steps should be few and easy, and the corresponding motions of the arms and body unaffected, modest, and graceful”. Surely this is still true. The RSCDS style is strongly influenced by ballet, but ours shouldn't be. However, “unaffected” doesn't mean “sloppy” — dancers should stand up straight and tall rather than slouching. Sharp studied traditional dancers before he started interpreting Playford, and realised that the way to move forward is to lean forward — sticking your leg out doesn't do much! Dancing is a controlled fall (unless you're doing Argentine Tango). If you're not travelling, your head and body need to be above your feet, but if you're travelling they aren't — just as in skating. Sharp also says that to do this the body needs to be in more or less a straight line from head to foot — no bend at the neck or waist, or sag at the knees. He talks about dancing with the whole body, not just the legs.

The RSCDS style is strongly influenced by ballet, but ours shouldn't be. However, “unaffected” doesn't mean “sloppy” — dancers should stand up straight and tall rather than slouching. Sharp studied traditional dancers before he started interpreting Playford, and realised that the way to move forward is to lean forward — sticking your leg out doesn't do much! Dancing is a controlled fall (unless you're doing Argentine Tango). If you're not travelling, your head and body need to be above your feet, but if you're travelling they aren't — just as in skating. Sharp also says that to do this the body needs to be in more or less a straight line from head to foot — no bend at the neck or waist, or sag at the knees. He talks about dancing with the whole body, not just the legs.

Chris and Ellis Rogers wrote an article in the Winter 2001 “English Dance & Song” (the magazine of the English Folk Dance and Song Society), in which they talked about good posture — they say it's not something you can pick up when dancing and drop in the rest of your life — the muscles need to be firmly and permanently honed.

Imagine that a string runs through from the top of your head to between your legs. Imagine that someone is pulling gently up on that string. The top of your head moves up, your neck stretches, your chin tucks in very slightly. Your shoulders drop, your torso lifts from your hips, your stomach pulls in gently, and the base of your spine stretches towards the floor. Your weight moves onto the balls of your feet; your heels rest lightly on the floor. When you can maintain this comfortably while moving and breathing easily, you have achieved good posture.

But can you teach this? First you need to be able to do it yourself; you won't convince anyone otherwise. If you read those words out and do the actions as you mention them, maybe you will give people the idea — I don't know. Chris and Ellis say that good posture is something you will learn from few dance technique workshops, and also that one workshop is not enough —

it must be repeated and reinforced and practiced until it is firmly in place

On Monday, March 3, 2008, bonnie treacher from henrey cort fareham wrote:

Hi my name is bonnie i love to dance and i would like to teach dancing i am very happy to help you teach babys and todla now but when i get older i would like to teach kids and adolts thanks for lisering .

On Monday, March 10, 2008, Colin Hume from Letchworth wrote:

Bonnie -

Thanks for your messages. I don't do any dances for babies and toddlers, though I sometimes run a Family Dance - I ran one at Whitby Folk Week last August and I will be running one this August. What sort of dancing do you do? Where have you done Folk Dancing? Please give your full email address if you would like a personal reply.

On Thursday, August 13, 2009, Hilary from North Yorkshire wrote:

I agree - club callers ought to teach technique.

And I agree absolutely that "harping on" is not the way to do it.

I would go further - not just club callers. When I call for ceilidhs I try to teach technique to absolute beginners, without making a big deal of it, but I'm sure the odd sentence or two thrown in here and there is perfectly acceptable, and actually at times essential or the proceedings cannot proceed.

The main technique points I find essential are: how to make up sets (i.e., not pushing in, wave a hand for more couples), wave if lost in a change-partner dance, bow/curtsey and smile and say "thank you" at the end of a dance. I indicate how many steps in a move by saying e.g. "circle left ... 5,6,7 and back,2,3,4,5,6,7,8." and similar, and I TRY to dissuade dancers from crushing their thumbs into other people's elbow joints in Strip the Willow, because in my youth I got bruised elbows too many times.

With many audiences it would be inappropriate to do more - e.g. children under 7 are doing well to dance at all, but with adults who have been to a few ceilidhs before, I don't see any reason not to throw in a few technique points, particularly if there are some more experienced dancers who are probably getting very bored among a complete beginners audience - why not encourage them to do a high-5s as the lines go forward and back, or to try a ballroom hold swing rather than cross-hands and skip round? And how can you do "step to partner" or baskets etc with an audience who've never done it before, unless you teach?

I have in the past been appalled at some ceilidh callers whose own knowledge of technique is so lacking that they even get the men and women standing the wrong way round. Could all ceilidh callers who have got the job by drawing a short straw, please take it upon themselves to go to a folk dance club often enough to learn the basics, at least! I won't name names, except - Jolene on The Archers...!

Could all ceilidh callers who have got the job by drawing a short straw, please take it upon themselves to go to a folk dance club often enough to learn the basics, at least! I won't name names, except - Jolene on The Archers...!

On Wednesday, October 26, 2011, Melanie Collier from West Wales wrote:

I have stumbled upon your site a couple of times while browsing and thinking about reasons why dance technique is important. I too encounter dancers who think that learning technique and having a good time are mutually exclusive. I'm enjoying reading what you've written on teaching and technique and agree. I am especially fascinated in that the ideas hold true for different styles of dance. I don't teach English Country Dance - I teach belly dance! Thanks for sharing your experience.

Dance Technique

Adama Sevani, better known as Robert Alexander III from the Step Up dance franchise once said, “Dance can change lives. One move can set a whole generation free, make you think you're worth something, and some moves can give you hope that you're special." Is it really necessary to go through several stages of research. To begin with, it is necessary to find out what a dance is, then to analyze the stages of evolution, only at the end to conclude what a dance really is. Let's start with a historical background: “Dance is rhythmic, expressive body movements, usually built into a certain composition and performed with musical accompaniment. Dance is the oldest of the arts, since it is able to reflect the need of a person, dating back to the earliest times, to convey to other people their joy or sorrow through their body. All important events in the life of a primitive man were celebrated with dances: birth, death, war, the election of a new leader, the healing of the sick. The dance expressed prayers for rain, for sunlight, for fertility, for protection and forgiveness. Dance movements originate from the basic forms of human movement - walking, running, jumping, bouncing, jumping, sliding, turning and swinging.

One move can set a whole generation free, make you think you're worth something, and some moves can give you hope that you're special." Is it really necessary to go through several stages of research. To begin with, it is necessary to find out what a dance is, then to analyze the stages of evolution, only at the end to conclude what a dance really is. Let's start with a historical background: “Dance is rhythmic, expressive body movements, usually built into a certain composition and performed with musical accompaniment. Dance is the oldest of the arts, since it is able to reflect the need of a person, dating back to the earliest times, to convey to other people their joy or sorrow through their body. All important events in the life of a primitive man were celebrated with dances: birth, death, war, the election of a new leader, the healing of the sick. The dance expressed prayers for rain, for sunlight, for fertility, for protection and forgiveness. Dance movements originate from the basic forms of human movement - walking, running, jumping, bouncing, jumping, sliding, turning and swinging. The totality of such movements gradually turned into the “pas” of traditional dances. The main parameters of the dance are rhythm - a relatively fast or relatively slow repetition and modification of basic movements; drawing - a set of movements in the composition; dynamics - variation in the scope and intensity of movements; technique - the level of body control and skill in performing basic steps. In many dances, gestures are also important, especially hand movements. The dance has different means of expression, namely: harmonious movements and postures, plasticity and facial expressions, dynamics "variation of the scope and intensity of movements", amplitude, tempo and rhythm of movement, spatial pattern, composition, costume and props.

The totality of such movements gradually turned into the “pas” of traditional dances. The main parameters of the dance are rhythm - a relatively fast or relatively slow repetition and modification of basic movements; drawing - a set of movements in the composition; dynamics - variation in the scope and intensity of movements; technique - the level of body control and skill in performing basic steps. In many dances, gestures are also important, especially hand movements. The dance has different means of expression, namely: harmonious movements and postures, plasticity and facial expressions, dynamics "variation of the scope and intensity of movements", amplitude, tempo and rhythm of movement, spatial pattern, composition, costume and props.

Mastering dance skills is closely related to the activation of attention, thinking, memory, the formation of self-control, ways of developing a sense of rhythm and tact. In the process of learning to dance, it is possible and necessary to use improvisation (when dancers invent movements directly during the performance), broken movements.

For those who have never been involved in dancing, the above will remain ordinary words, a little familiar, but still, words. For everyone else who is even a little connected with dancing, each word has its own separate meaning. However, do not forget that emotions also depend on the plot of the dance. The dancer can be of any height and weight, during the classes the inner world is revealed through a kind of dance technique: expressiveness of movements, gestures, facial expressions, postures, understanding one’s body in space and understanding the work of muscle groups, glorifying the beauty and harmony of the human body, sentimentally gentle manifestations . The reason for the success of the performance lies in the high technique of movements, which leads to coherence, lightness, ease and expressiveness of the dance performance. Under the technique of performing dance movements is understood the ability to correctly and accurately perform dance movements. “The content and depth of a choreographic work can be accurately revealed only with the help of an accurate performing technique of dance. Where there is no precisely developed dance technique, there can be no true art,” says N. Tarasov, an outstanding choreographer and teacher. Any choreographic work, that is, a dance, consists of movements, each of which, in turn, consists of several elements. Each genre of choreography, whether it be classical, folk or modern dance, has its own set of basic elements and movements, created over many centuries of the existence of dance art. With the help of these movements, complemented by gestures and facial expressions, dance performers convey to the viewer not only the thoughts, feelings, experiences of the characters, but also the very content of the dance work. No matter how different the movements of dances of different genres are from each other, they will not only affect the viewer if they are performed technically, that is, competently and accurately. “Precision is not a template, not simple professional pedantry, but a lively sense of dance, which determines the perfection of performing skills.

Where there is no precisely developed dance technique, there can be no true art,” says N. Tarasov, an outstanding choreographer and teacher. Any choreographic work, that is, a dance, consists of movements, each of which, in turn, consists of several elements. Each genre of choreography, whether it be classical, folk or modern dance, has its own set of basic elements and movements, created over many centuries of the existence of dance art. With the help of these movements, complemented by gestures and facial expressions, dance performers convey to the viewer not only the thoughts, feelings, experiences of the characters, but also the very content of the dance work. No matter how different the movements of dances of different genres are from each other, they will not only affect the viewer if they are performed technically, that is, competently and accurately. “Precision is not a template, not simple professional pedantry, but a lively sense of dance, which determines the perfection of performing skills. Accuracy allows the dancer to acquire plastic harmony, self-confidence, and creative activity. The concept of "near", "near", "approximately" is not compatible with the dance technique. The slightest rhythmic and plastic inaccuracy indicates that the performer does not have mastery,” writes N. Tarasov. That is why, teaching children to dance, developing performance qualities, it is necessary from their first steps in choreography to form the ability to accurately and correctly perform all dance movements.

Accuracy allows the dancer to acquire plastic harmony, self-confidence, and creative activity. The concept of "near", "near", "approximately" is not compatible with the dance technique. The slightest rhythmic and plastic inaccuracy indicates that the performer does not have mastery,” writes N. Tarasov. That is why, teaching children to dance, developing performance qualities, it is necessary from their first steps in choreography to form the ability to accurately and correctly perform all dance movements.

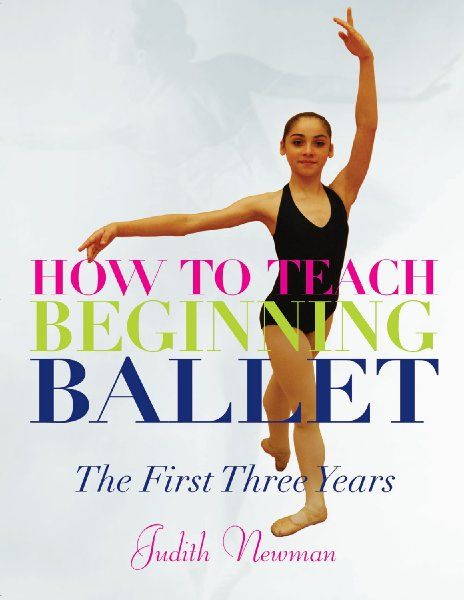

The driving force behind all this is the desire of the dancer to be different from others, and the absence of strict norms allows you to observe the only rule - everyone has the right to individuality. High dance technique does not appear on its own, it is formed gradually, from lesson to lesson for several years, and along with it the mastery of performance grows. The technique of movements depends on the preparedness of the entire motor apparatus of the trainees, on the training and education of the entire body of the child - muscles, psyche, nervous system. Work on performing technique begins at a young age with the setting of the body, training of individual muscle groups and the entire body of the pupils, the formation of the simplest skills of various movements in them. This is achieved by performing exercises for various parts of the body: legs, arms, head, body - and each of these exercises is performed according to certain rules. The firm conviction of the majority of outstanding choreographers that only a school of classical dance is able to develop a high dance technique among students.

Work on performing technique begins at a young age with the setting of the body, training of individual muscle groups and the entire body of the pupils, the formation of the simplest skills of various movements in them. This is achieved by performing exercises for various parts of the body: legs, arms, head, body - and each of these exercises is performed according to certain rules. The firm conviction of the majority of outstanding choreographers that only a school of classical dance is able to develop a high dance technique among students.

The school of classical dance, which has a huge range of technical and expressive means, is the basis used by performers of all genres of stage choreography. “All genres of stage choreography use, to one degree or another, the performing technique of classical dance, which helps to achieve a higher and more perfect performance level,” N. Tarasov interprets.

Thus, in the educational work on mastering the art of dance, it is necessary to use the system of classical dance in order to form in children the skills of performing dance elements and movements. But, most importantly, this system of exercises helps to strengthen muscles, posture, develop such qualities as stability, flexibility and other indicators of the dancers' physical readiness for learning and performing dance. From all of the above, you can make the only right choice.

But, most importantly, this system of exercises helps to strengthen muscles, posture, develop such qualities as stability, flexibility and other indicators of the dancers' physical readiness for learning and performing dance. From all of the above, you can make the only right choice.

Dance technique is of great importance for the formation of the performing skills of dancers. Dance movements honed to automatism cease to occupy the child's thoughts, and then all his attention goes to the music and the nature of the image that he reflects in the dance, expressing his own attitude to the movements performed. So the dance technique becomes the basis of musicality, expressiveness and individuality of performance.

Thus, the teacher must use maximum means in order to strike and then improve the technique of dance movements performed by children, which will certainly lead to the desired result of learning in a choreographic group - the mastery of dance performance.

It's easy to learn oriental dance - Start Fit University

Article navigation:

- 2.

Mastering Key Dance Techniques

Mastering Key Dance Techniques - 3. What goals can be achieved with belly dancing

Updated on 04/27/2022

Alina Lychagina

Sports nutritionist, teacher of courses in “Sports nutrition”

All materials on the site are for informational purposes only.

From this article you will learn:

Most modern men and women experience the desire to learn to dance. However, not everyone is ready to visit the studio regularly, but lessons for beginners can be viewed at any free moment.

In addition, many are stopped by a feeling of embarrassment or self-doubt in their abilities. It is enough to watch a lesson in belly dancing or another dance direction to discover such talents in yourself.

What makes oriental dance interesting

Each lesson, even at the beginner level, is a great opportunity to train your joints, muscles and spine. It is belly dancing that allows women to liberate themselves and be able to overcome their own stress.

In addition, this is just a wonderful sight, which men of different ages love to admire so much. Getting an attractive body shape has never been so real. Add to this tightened abdominal muscles, and we get an answer to the question of the popularity of this dance direction.

Today, there are many teaching methods. Dance lessons for beginners Vina and Nina can significantly improve posture and body flexibility. There are quite a lot of movements that are performed in this type of dance.

Among them are the following:

- hip strikes;

- eight;

- turns;

- shaking;

- barrel;

- waves, etc.

Mastering key dance techniques

The basic movements that the lesson for beginners and following provide us with are divided into 2 main groups. This is the upper part of the body, namely the upper abdomen, chest, arms, neck and head. As for the lower part, these are the legs, thighs, buttocks, lower abdomen.

So, the first dance lesson often talks about what the main and warm-up techniques should be in order to work out the technique of performance, as Vina and Nina Bidashi say.

Hip movements. We put our feet shoulder-width apart, and the socks look parallel to each other. The chin should be slightly raised up, and the arms should be spread apart. Now, on the count of “one”, the right thigh goes to the right, and on the count of “two”, the left thigh goes to the left side.

Let's try moving forward from ourselves and in the opposite direction. To do this, put your feet closer to one another. On the first count, our hips should go forward, on the second count, go back. Now we can connect a couple of the described movements into one complete cycle, when we describe a full circle with the hips.

Lessons on neck movements. Despite the fact that this part of the body is more difficult to train, such manipulations are also given considerable importance. We fold our hands in our palms at chest level and begin to tilt our heads to one side, then to the other. Now, for each count, we begin our dance - we tilt our heads to the side, and back and forth. To complicate the task, it is better to do this in the form of head rotations to the accompaniment in compliance with the size.

Now, for each count, we begin our dance - we tilt our heads to the side, and back and forth. To complicate the task, it is better to do this in the form of head rotations to the accompaniment in compliance with the size.

Moving on to chest movements. All beginners Vina and Nina are preparing for the fact that it is important to control independence and independence from hip movements. So, at the expense of "one" we stretch our chest up, at the expense of "two" we go down. Similar movements are performed to the right, and then to the left. If we combine these movements in one row, as in the previous exercises, then we can already make circular movements with the chest.

What goals can be achieved with belly dancing

Each dance lesson that Vina and Nina Bidashi show us is aimed at working out certain parts of the body. This is a kind of fitness course, which will also give you dancing skills, as well. Lessons for beginners last approximately 30 minutes each.

Belly dancing will not reveal its secrets immediately. At first, it is a big problem for beginners to even keep their hands on their weight for a long time, as required by the dance. If you continue to practice regularly, then your hands will gradually get stronger, and this problem will disappear.

Many rhythmic movements are aimed at ensuring that each dancer can lose excess subcutaneous fat, especially in the waist and abdomen. Just imagine how great it is - not only to master the dance, but also to make your figure more attractive, and even lose weight! Dance lessons provide an opportunity for excellent development of plasticity and coordination of movements, and besides, they perfectly train the muscles of the main muscle groups. A good load can definitely be expected by the muscles of the back, abdomen, chest and arms.

In order for the belly dance lesson given by Vina and Nina not to be in vain, take care in advance about comfortable clothes that would not constrict your movements.